| Norman Rockwell Famous Artwork | |

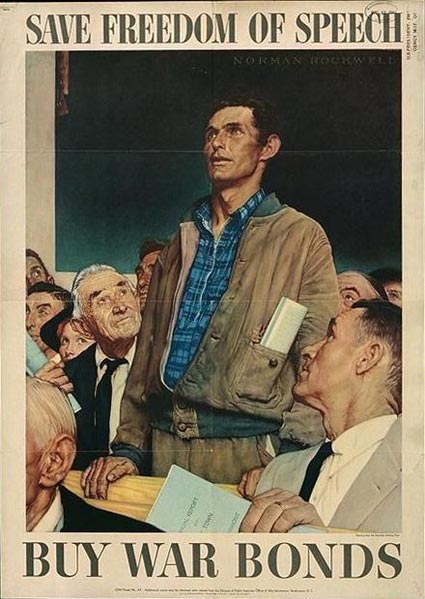

| Freedom of Speech, 1943 | |

| Freedom from Want, 1943 | |

| Freedom of Worship, 1943 | |

| Freedom from Fear, 1943 | |

| The Problem We All Live With, 1964 | |

| Breaking Home Ties, 1954 | |

| Russian Schoolroom, 1967 | |

| Rosie The Riveter, 1943 | |

| Complete Works |

Norman Percevel Rockwell was America’s most loved illustrator who was initially insecure about his works, preferring to call them illustrations rather than art. But whatever they were called, he and his pieces gained fame and popularity because he was able to put across nostalgia in his works, a kind of utopia where everything was simple and everyone was nice and kind – the American dream summed up. He told visual stories about everyday life, indeed it was in his illustrations where one could feel and taste the American spirit. He shared the same hopes and dreams with everybody when he himself said, “I paint life as I would like it to be”, thus becoming both hero and friend to everybody. Famous filmmaker Steven Spielberg had even described him as the best person who had ever painted the American dream.

Norman was born on February 3, 1894 in New York. His father was Jarvis Waring Rockwell, Sr. and was a manager for a textile firm, while his mother was Anne Mary Hill. He had an older brother named Jarvis Jr.

At the age of 14, Norman left high school to study art first at the Chase Art School, then at the National Academy of Design, and lastly at the Art Students League where he graduated. Even as a student, Norman had shown both sense of humor and discipline. In 1912, when he was still a student and just 18 years old, Norman was given a big break when he was commissioned to do the illustrations for the book titled “Tell Me Why: Stories About Mother Nature” by Carl Harry Claudy.

Upon graduation in 1913, Norman was immediately hired as Art Editor for Boy’s Life, a publication by the Boy Scouts of America. His first published cover for this magazine was titled “Scout at Ship’s Wheel” for its September 1913 edition.

In 1916, Norman moved to another part of the city. He shared an apartment with a cartoonist working for the Saturday Evening Post named Clyde Forsythe, and it was Clyde who helped him submit his illustration titled “Mother’s Day Off” to that publication. Within one year, Norman had already done 8 cover illustrations, and in the span of four decades working for the Saturday Evening Post, he was able to do a total of 332 original cover illustrations. Such was the popularity Norman had gained that the Post needed an automatic 250,000 increase in copies whenever the cover was done by him.

His success led him to do covers for a lot of other magazines like Life Magazine, Literary Digest, People’s Popular Monthly, The Literary Digest, Leslie’s Weekly, and The Country Gentleman. In fact, it was while doing an illustration for The Literary Digest in 1916 when he met his first wife Irene O’Connor. She was his model for the illustration titled “Mother Tucking Children into Bed”.

By the 1920s, Norman had also been doing illustrations for advertisements of brands like Jell-O and Orange Crush. Also during this year, he painted a calendar for the Boy Scouts of America, and continued doing so until 1976.

In 1930, Norman divorced his wife and because of depression, decided to stay for some time with his friend Clyde, who was then living in California. It was while there that Norman painted “The Doctor and the Doll”, one of the more famous covers he had done for The Post. It was also while there that Norman met his second wife, a school teacher named Mary Barstow. They returned to New York and had three children, Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter.

In 1935, Norman was commissioned by Heritage Press to do the art work for the deluxe edition of “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn”. He also did the illustrations for more than 40 other books, as well as illustrations for catalogs, stamps, music covers, and murals for an inn in New Jersey called Nassau Inn. He painted the 13-foot “Yankee Doodle Dandy” mural in 1937 which was a visual depiction of the song with the same title.

During World War II, Norman created several series which featured fictional characters he himself created for The Post. These series were believed to be Norman’s contribution to the war effort, specifically the effort to sell war bonds. One was Willie Gillis, whose career as a Private in the Army was followed by more than 4 million readers in 11 cover illustrations, starting from his induction until his discharge.

During World War II, Norman created several series which featured fictional characters he himself created for The Post. These series were believed to be Norman’s contribution to the war effort, specifically the effort to sell war bonds. One was Willie Gillis, whose career as a Private in the Army was followed by more than 4 million readers in 11 cover illustrations, starting from his induction until his discharge.

There is also Rosie the Riveter. This fictional character created by Norman in 1943 served as a cultural icon as she represented all the American women working in factories during the War to make ammunitions and war supplies. She was a symbol of women empowerment. So powerful and moving were Norman’s illustrations that as much as 11,000,000 women began volunteering for assembly line work. Some of the more famous Rosie the Riveter illustrations depicted Rosie taking a lunch break with a rivet gun resting on her lap, another was Rosie reading a book by Karl Marx, and another was Rosie inside the cockpit of a fighter plane while another woman was refueling it.

The Four Freedoms, also created in 1943, was inspired by the State of Union Address by Franklin Roosevelt in 1941 where he named four essential human rights. These four human rights were depicted by Norman, and they were the “Freedom of Speech”, the “Freedom of Worship”, the “Freedom from Fear”, and his “Freedom from Want” which became an emblem for the American Thanksgiving. This series is the only paintings done by an American that has ever been published on a global scale.

Norman’s second wife, Mary, died in 1959. In 1961, he was again married to Molly Punderson, an English teacher. He died of emphysema at the age of 84 on November 8, 1978.

Norman Rockwell’s compositions are known for their painstaking detail, paying attention to texture and color. His figures are known for being expertly exaggerated while still maintaining their realism. Among the awards he received was the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 for his “vivid and affectionate portraits”. This is the highest honor given to a civilian.