| Edward Hopper | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 22, 1882 Nyack, New York |

| Died | May 15, 1967 (at age 84) New York City |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Painting |

| Edward Hopper Famous Paintings | |

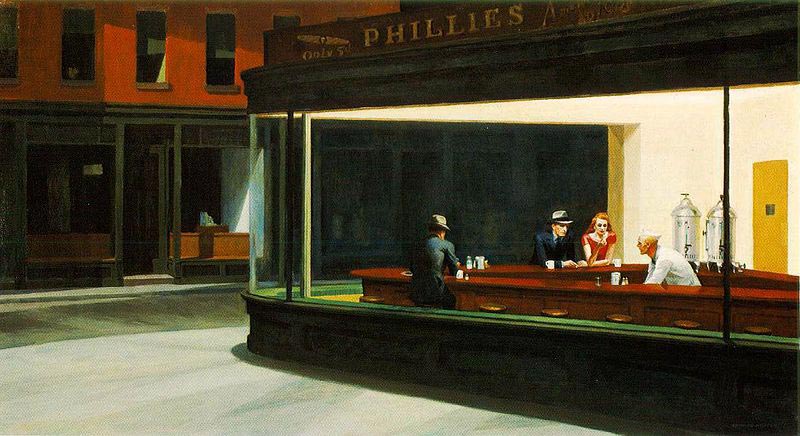

| Nighthawks, 1942 | |

| Automat, 1927 | |

| Early Sunday Morning, 1930 | |

| Room in New York, 1932 | |

| Hotel Lobby, 1943 | |

| Chop Suey, 1929 | |

| Office at Night, 1940 | |

| Office in a Small City, 1953 | |

| Girl at Sewing Machine, 1921 | |

| Complete Works |

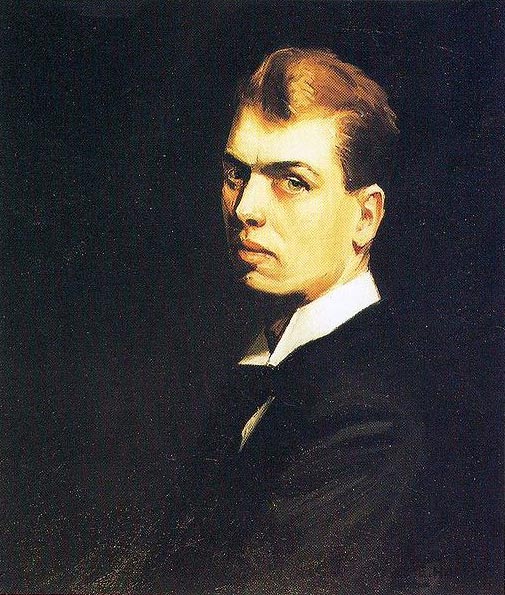

Edward Hopper is considered one of the most seminal modern American artists of the 20th century. Hopper was a New York native, born on July 22, 1882 in upper Nyack, which was a yacht-building community on the Hudson River. Raised in a relatively comfortable middle-class life, he was one of two children from a merchant couple of Dutch ancestry. He and his sister were privileged with good education, and were raised Baptist in a somewhat conservative household.

As a student, he excelled in his studies, especially at drawing, which he took on at an early age of five. His parents, both culturally and artistically inclined, encouraged the young Hopper and readily supplied him with resources such as books, magazines and art materials. As an adolescent, Hopper could be considered prolific as he had already experimented with various media such as pen and ink, charcoal, watercolor, and oil.

In 1899, Hopper formalized his art training by undertaking a correspondence course and later on enrolling at the New York Institute of Art and Design. He considered French masters and impressionists Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas as his early influences. A professor, fellow artist Robert Henri, instilled in Hopper the courage to paint with emotion, with a statement, or with a point of view. This would become very evident in Hopper’s later and most definitive works.

After art education, however, Hopper found himself in the cutthroat advertising industry, churning out illustrations and cover designs for magazines. He did not like this situation which stifles his creativity and only persisted with it for the financial gain, up until the 1920s. He escaped this commercial milieu as often as he could, travelling to Europe, particularly in Paris. While numerous other painters and artistic movements were at their height in the French capital, Hopper gravitated toward works and styles that appealed to him most, regardless of fad or fashion, falling in love for instance with 17-century master Rembrandt’s famous work Night Watch.

After art education, however, Hopper found himself in the cutthroat advertising industry, churning out illustrations and cover designs for magazines. He did not like this situation which stifles his creativity and only persisted with it for the financial gain, up until the 1920s. He escaped this commercial milieu as often as he could, travelling to Europe, particularly in Paris. While numerous other painters and artistic movements were at their height in the French capital, Hopper gravitated toward works and styles that appealed to him most, regardless of fad or fashion, falling in love for instance with 17-century master Rembrandt’s famous work Night Watch.

Hopper continued to struggle with his artistic vision and personal life, returning to New York and reluctantly taking up commercial illustrations again for a living. After an influential trip to Massachusetts, Hopper came up with among his first nautical-inspired realist suburban scenery, and was able to sell his first painting, Sailing (1911). Hopper moved to Greenwich Village in New York and worked on more commissioned illustrations such as movie posters.

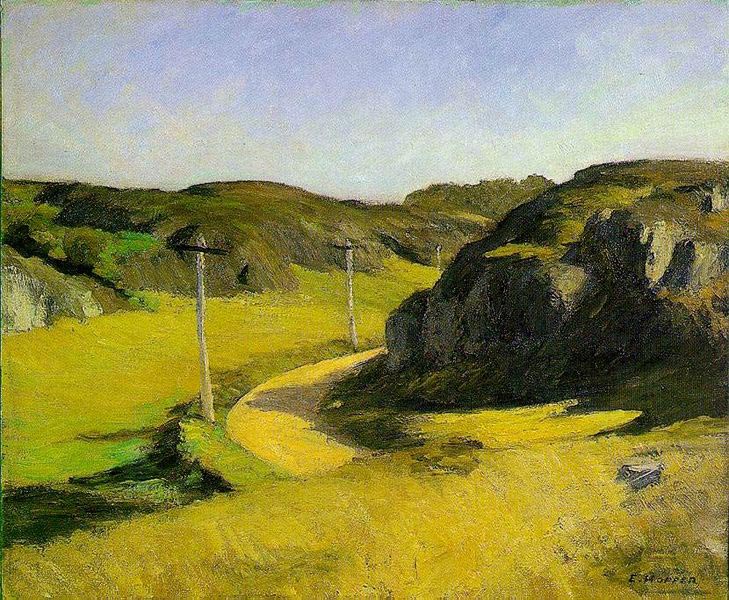

While Hopper would be most known for his oil paintings for the entirety of his artistic career, Hopper also produced some etchings during this period, mostly of Parisian and New York urban scenes. He also explored more of the watercolor medium with his trips to artistic communities and niches in New England, portraying natural scenery and nautical themes.

While Hopper would be most known for his oil paintings for the entirety of his artistic career, Hopper also produced some etchings during this period, mostly of Parisian and New York urban scenes. He also explored more of the watercolor medium with his trips to artistic communities and niches in New England, portraying natural scenery and nautical themes.

Edward Hopper broke into prominence around the 1920s, coinciding with his partnership with future wife Josephine Nivison. He had begun to find his distinctive style, utilizing a visual technique similar to Impressionism but ending up more in a Realist manner with the considerable detail that he still paid attention to. Critics have dubbed Hopper’s distinctive style “soft realism.”

He painted modern cityscapes and urban dwellers in a moody, dark palette. At the same time, Hopper’s continued on with his alternative idyllic subjects such as seascapes and rural scenery. Hopper’s works were marked with a calculated discipline in composition, with clever and compelling visual balance that draws the viewer’s eyes to desired subjects in the frame. A viewer would sense highly dramatic tension from Hopper’s scenes, especially those involving human subjects. Void of dynamism or physical action, the subjects communicated instead with nuances. Hopper’s works usually expressed and elicited solitude, withdrawal, pensiveness, regret, and other emotional themes.

Despite the Great Depression that hit in the 1930s, Hopper was fortunate to have enjoyed even more prominence, with his works being recognized and bought by the most important museums in America. He continued to be extremely productive, coming up with works well into the second half of the 20th century. His most famous and iconic paintings—in his signature introspective mood depicting human life against the backdrop of the metropolis—include Automat (1927), Chop Suey (1929), Hotel Room (1931) and Nighthawks (1942).

Hopper had achieved considerable success and financial stability that he lived a comfortable life, affording him to continue pursuing his distinctive style, his pace of work, and his penchant for travelling for inspiration. Despite some health problems in the 1950s and 1960s and a slowdown in his creative work, he still managed to bring forth iconic and continually important works. He is one of few artists who held steadfast to his signature style, making his works one of the most recognizable and iconic in modern American art history.

With Edward Hopper’s death in 1967, and, subsequently, his wife’s 10 months later, their collection of his more than three thousand works went mostly to the Whitney Museum of American Art—rightfully so for this American artist who successfully and every so poignantly captured the tension and irony of modern American life.