| The Vitruvian Man | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1487 |

| Medium | Pen and ink with wash over metalpoint on paper |

| Location | Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, Italy |

| Dimensions | 13.5 × 10.0 in |

| 34.4 × 25.5 cm | |

| Famous Paintings by da Vinci | |

| The Last Supper | |

| Mona Lisa | |

| Vitruvian Man | |

| The Baptism of Christ | |

| Annunciation | |

| Lady with an Ermine | |

| Ginevra de’ Benci | |

| Adoration of the Magi | |

| St. Jerome in the Wilderness | |

| View Complete Works |

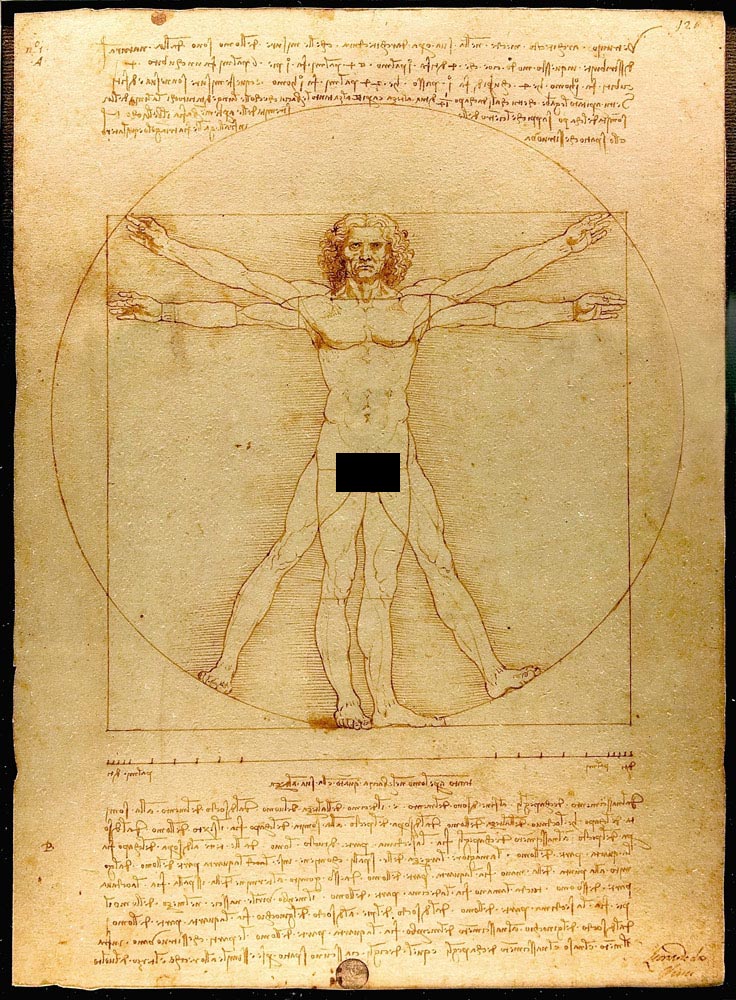

Leonardo da Vinci drew The Vitruvian Man in approximately 1487 in one of his notebooks. This world-famous drawing is also known as the Canon of Properties or Proportions of Man. The Vitruvian Man blends art and science and showcases da Vinci’s interest in proportion. It also provides an example of da Vinci’s attempt to make connections between man and nature. The drawing currently resides in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, Italy and is rarely shown.

History

Leonardo da Vinci had a great interest in science as well as art. While the concepts of human proportion had been studied for centuries, his drawing was unique due to some modifications he made based upon his own observations. Multiple examples of anatomical sketches exist and may have served as inspiration or source material for da Vinci. However, his primary inspiration came from the work of Vitruvius, a famous Roman architect. His background in geometry and anatomy gave da Vinci a unique ability to apply geometric principles to his artwork and The Vitruvian Man provides an excellent example of his ability to blend science and art.

The Drawing

The Vitruvian Man is a pen and ink drawing done on paper with a wash over metal-point accompanied by handwritten notes. In the drawing, two male figures are superimposed upon each other. The figures are shown with arms and legs extended in differing degrees of extension. One figure shows the legs slightly apart and the arms extended straight out from the shoulders. The other figure shows the legs moderately spread and the arms extended partway above the shoulders. In both figures, the head and torso are completely superimposed. The male figures are inscribed within a circle and a square, showing the geometric proportion of the human body. Markings upon the bodies serve to identify points used in establishing proportional measurements. In addition, the drawing includes shading and details indicating musculature and anatomical elements such as joints and genitalia.

The Notes

The drawing includes handwritten notes above and below the drawing. The notes are based upon the work of Vitruvius who described the human body as an example or source of proportion in Classical architecture. The text above the drawing lists specific measurements based upon the human body. In this paragraph, da Vinci inscribes some of Vitruvius’ observations and provides geometric ratios based upon the extension of the arms and legs.

The notes beneath the drawing continue listing specific anatomical proportions. While the top portion provides specific measurements, the bottom listing focuses on proportions of the human body. For example, da Vinci noted the span of outstretched arms is equal to height. Each point used in determining the listed proportions are marked in the drawing and a line indicating length or dimension is included beneath the anatomical figures.

Interpretation

While da Vinci clearly references Vitruvius and uses his work as a basis for The Vitruvian Man, this sketch goes beyond the mathematical proportions of the human body. While Vitruvius considered the body a source of architectural proportion, da Vinci extended the observations and work by correlating the symmetry of human anatomy to the symmetry of the universe. In da Vinci’s drawing, changes to the original source material include shifts in the position of the enclosing square and variations in the height of the extended arms. These changes show a greater understanding of anatomy gained through da Vinci’s study of the human body. Although the drawing consists of two superimposed images, the combinations of limb positions allow 16 different poses to be observed.

In addition to the anatomical and artistic value of The Vitruvian Man drawing, mathematicians have studied the drawing extensively and found numerous proportional rules and formulas in da Vinci’s work. The drawing aligns to an octagon, which serves as a geometric framework for the proportions of the human body. Close analysis of the drawing shows each individual proportion adheres to the canon recommended by Vitruvius and still holds up to modern medical and mathematical studies.

The Vitruvian Man is one of the most well-known and easily recognized images of Renaissance art and serves to showcase the blend of art and science which emerged during this period. The drawing, found in da Vinci’s notebooks, was intended to be part of his personal notes and observations of the human body. Yet, it still continues to be a vibrant and resonant image appearing in numerous modern contexts to represent the same blend of science and art.