In 1893, a Muslim businessman named Dada Abdullah informed Gandhi that he had a cousin in South Africa who needed the services of a lawyer. Gandhi asked about the salary and then accepted the offer. He expected that it was only a one-year contract in the colony of Natal, which was also ruled by the British empire.

The Making of a Civil Rights Activist

Gandhi was only 23 years old when he sailed for South Africa in April 1893. He immediately experienced harsh treatment and discrimination upon arrival. He was forbidden to sit with white passengers in a stagecoach and was ordered to sit on the floor. Gandhi refused, and as a result, he was physically assaulted. On another occasion, he was sitting in the first-class compartment of a train and was ordered to transfer to third class. Gandhi refused, and he was hurled off the train. He remained on the train station platform and spent the night there, thinking about whether he should go back home to India or fight for his rights. Gandhi decided to stay, and the next day, he was able to travel by train. Not long after, he entered a Durban court and was told by the magistrate to take off his turban. Gandhi did not comply with the instruction. Before he arrived in South Africa, Gandhi reasoned to himself that he was primarily a British citizen and, secondly, an Indian. And so, he was deeply disturbed by the act of discrimination committed against him and other Indians. He was puzzled over how other human beings could derive satisfaction from treating others harshly. And from then on, he began to doubt how the British empire valued its Indian citizens.

In May of 1894, Gandhi’s business with Abdullah’s cousin ended, so his Indian friends prepared a goodbye party for him before he sailed home for India. However, Gandhi decided to extend his stay because he planned to help Indians fight against a bill that sought to deny them voting rights. The white rulers maintained that voting was a right reserved for Europeans only. Gandhi requested the British colonial secretary to reexamine his opinion on the matter. Gandhi failed to stop the bill’s passing, but his efforts created awareness about the situation of Indians in South Africa. In 1894, he created the Natal Indian Congress, and with this organization, he brought together Indians in South Africa and gave them political strength.

In 1900, Gandhi actively participated in the Boer War by creating a corps of stretcher-bearers and naming it the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. The Natal Indian Ambulance Corps was medically qualified and properly trained to help on the battlefield. He created this corps to prove to the British authorities that Indians were loyal citizens of the British Empire. Gandhi was also eager to prove that Hindus were also physically strong and could work in dangerous situations. He brought together 1,000 volunteers who served British soldiers in their fight against the Boers. In places where the ground was too difficult for ambulances, Gandhi and his men rescued wounded soldiers on the front lines and carried them for several kilometers to temporary hospitals. For their efforts, Gandhi and 37 members of the ambulance corps were awarded the Queen’s South Africa medal.

When the Transvaal government passed a new act mandating the registration of Indians and Chinese residents in the colony, Gandhi saw the chance to implement nonviolent resistance or satyagraha. Gandhi instructed his allies that they must be ready to use nonviolent means to respond to the anticipated violence of the authorities. He added that the white rulers would inflict physical pain, arrests, and incarceration, but all protesters must meekly submit to all these. This is where Gandhi developed his philosophy of satyagraha or nonviolent resistance. Eventually, he developed his public speaking skills and political discernment and took these skills back home to India.

Gandhi’s Ideas on Racism

When he arrived in South Africa, Gandhi was not interested in entering politics. However, after being discriminated against, spat on, and called a parasite, Gandhi changed his mind and decided that the cruel rule of the British should be opposed. Consequently, he entered the political sphere and created the Natal Indian Congress. However, Gandhi turned his attention only to the oppression of Indians and overlooked the situation of Africans. Gandhi’s ideas on racism were controversial and sometimes disturbing to those who knew him. Sometimes Gandhi’s words reflected racism, as when he complained that Indians were maltreated like Kaffirs. Kaffir is a racial insult directed towards black Africans. It is possible that in his overzealous attempt to fight for his people’s rights, he missed the fact that black South Africans also fought for racial equality. In 1895, when Gandhi presented a legal brief that sought Indians’ voting rights, he argued that Indians and Anglo-Saxons came from the same genetic origins as the Indo-European peoples. And so, he asserted that Indians should not be classified with Africans.

Disillusionment with the Empire

When the Bambatha Rebellion erupted as a consequence of British taxation in the Natal Colony, Gandhi urged Indians in South Africa to form a stretcher-bearer group. Gandhi stated that military involvement would be favorable to Indians and would make them healthy. Later, Gandhi led a unit of stretcher-bearers made up of Indians and Africans alike. This unit served for two months before it was demobilized. After the rebellion was settled, the colonial authorities did not grant Indians the civil rights they had been demanding. This resulted in Gandhi’s disillusionment with the British empire and made him realize that non-cooperation may be a better means of fighting discrimination.

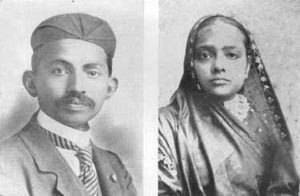

Gandhi was an admirer of the novelist Leo Tolstoy and was deeply influenced by his book, The Kingdom of God is Within You. In 1910, Gandhi created a community near Johannesburg and called it Tolstoy Farm. This peaceful community became the main office of his crusade of satyagraha. Gandhi, along with his wife, Kasturbai, headed home to India on the 9th of January, 1915. He took home with him the political maturity and determination that he had acquired in South Africa and would use them to help India achieve its independence from British rule.