General Sherman’s March to the Sea, also known as the Savannah Campaign, was conducted through Georgia from November 15 to December 21, 1864. This campaign was under the leadership of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman of the Union Army. It started with Sherman’s army leaving the decimated city of Atlanta on November 16, 1864 and came to an end on December 21 with the capture of port of Savannah. The March is considered to be the most disparaging movement against civilians during the American Civil War. In addition to that, it caused major damage, especially to infrastructure and industry.

General Sherman’s March to the Sea, also known as the Savannah Campaign, was conducted through Georgia from November 15 to December 21, 1864. This campaign was under the leadership of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman of the Union Army. It started with Sherman’s army leaving the decimated city of Atlanta on November 16, 1864 and came to an end on December 21 with the capture of port of Savannah. The March is considered to be the most disparaging movement against civilians during the American Civil War. In addition to that, it caused major damage, especially to infrastructure and industry.

Preparation

After capturing the city of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, General Sherman spent a few weeks preparing to change his base to the coast. He declined the Union’s idea to proceed through Alabama to Mobile, reasoning that after Rear Admiral Farragut blocked Mobile Bay in the previous month (August), the Alabama Port did not hold any military importance. Rather, Sherman decided to advance southeast for Charleston or Savannah. He also decided to study census records so as to know the best route that could provide enough food for his troops and horses.

Despite President Lincoln being skeptical and not wanting Sherman to enter the enemy territory prior to the election in November, General Sherman convinced Lieutenant General S. Grant to have the campaign in winter. Grant’s intervention gave Sherman the permission he so much needed, but he had to wait until after presidential election date. This campaign was designed by Grant and Sherman, and intended to be similar to Grant’s successful Vicksburg Campaign. For this reason, Sherman’s troops would reduce their need for traditional supply lines. Sherman used crop and livestock production data from the 1860 census, when he was planning for this march. The troops were to destroy cotton gins and storage bins since the Southerners used the cotton to trade for guns and several other supplies.

Opposing Forces

After Confederate General John Hood left Atlanta, he shifted his Tennessee army outside the city to recover from the earlier crusade. Earlier on, in October he started an attack toward Chattanooga, Tennessee, trying to move Sherman back over ground that both parties had fought for since May. Instead of alluring Sherman to fight, General Hood turned his troops to the west and rally into Alabama, ditching Georgia to Union Army. With this, Hood thought that raiding Tennessee, would force Sherman to follow. However, Sherman had projected for this kind of tactic and had sent General G. Thomas to Nashville to handle food. After the Confederate forces were cleared from Georgia, Sherman was able to move south despite facing scattered cavalry.

The March

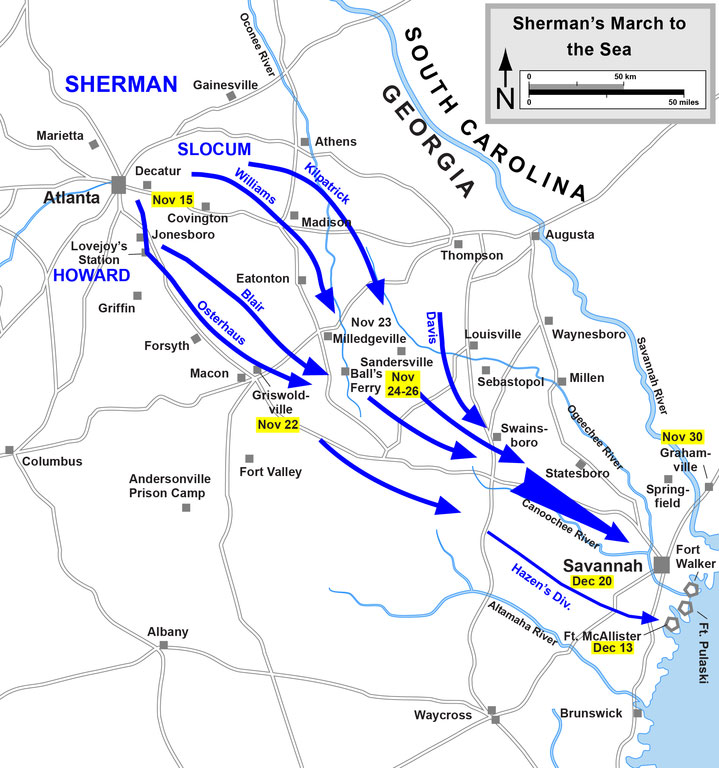

Sherman divided his remaining 62,000 men into two equal columns for the march. The right column was the Army of Tennessee, under the leadership of Major General Oliver Howard, while the left column was the Army of Georgia led by Major General Henry Slocum. Sherman also created a cavalry division under Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick to support the two wings. In addition to that, he had about 600 ambulances and 2,500 supply wagons. These two wings advanced in separate routes, the left wing headed for Augusta while the right one headed for Macon. Generally, these two wings stayed 20 to 40 miles apart at any particular time. After bypassing Macon and Augusta, the two wings headed for the Milledgeville. Sherman advance was opposed by Confederate cavalry with about 8,000 men led by Major General Joseph Wheeler and some divisions of Georgia militia led by Gustavus Smith.

Sherman divided his remaining 62,000 men into two equal columns for the march. The right column was the Army of Tennessee, under the leadership of Major General Oliver Howard, while the left column was the Army of Georgia led by Major General Henry Slocum. Sherman also created a cavalry division under Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick to support the two wings. In addition to that, he had about 600 ambulances and 2,500 supply wagons. These two wings advanced in separate routes, the left wing headed for Augusta while the right one headed for Macon. Generally, these two wings stayed 20 to 40 miles apart at any particular time. After bypassing Macon and Augusta, the two wings headed for the Milledgeville. Sherman advance was opposed by Confederate cavalry with about 8,000 men led by Major General Joseph Wheeler and some divisions of Georgia militia led by Gustavus Smith.

Even though, William Hardee had the general authority in Georgia, could not do much to discontinue Sherman’s progress. Sherman’s scavengers became recognized as bummers as they invaded plantations and farms. The state capital calmly surrendered on November 23, prompting Sherman to occupy the empty governor’s mansion and capitol building.

During the march, there were several battles involving Wheeler’s cavalry and Union army, but only two skirmishes were of any implication. The first battle took place on November 22 at the east of Macon city at Griswoldville. Here, the Georgia militia faced the Union infantry with devastating consequences. In the end, the Confederates lost 650 men, while the Union side suffered 62 casualties. The second battle happened on December 13 at the Ogeechee River, when the Union infantry attacked and captured Fort McAllister and therefore opened the rear entry to the port city.

One of the most controversial skirmishes was on December 9, at Ebenezer Creek, when Union’s Jefferson Davis detached the pontoon bridge before the contrabands, who were following the liberating armies, could cross the river. A number of them perished after drowning while trying to reach for their safety. This move was condemned by the Northern press after the march, however, Sherman supported his commander by saying that Davis did what was necessary at the moment.

On reaching the suburbs of Savannah on December 10, Sherman found out that Hardee had flooded the surrounding rice fields blocking him from linking with the U.S. Navy. However, after the successful capturing of Fort McAllister, Sherman was able to connect to the Navy fleet under Rear Admiral John Dahlgren. He was also able to get the supplies and siege artillery he needed in order to take Savannah. On learning about Sherman’s success to link with the U.S. Navy, Hardee escaped; and on December 20, Sherman led his troops across the Savannah River on a hastily constructed pontoon bridge. The following morning saw Mayor R. D. Arnold of Savannah give a formal surrender in exchange for General Geary’s pledge to protect the citizens and their properties. Sherman’s troops under the leadership of Geary’s division of the 20 Corps occupied the city in that same day.

The Aftermath of Sherman’s March

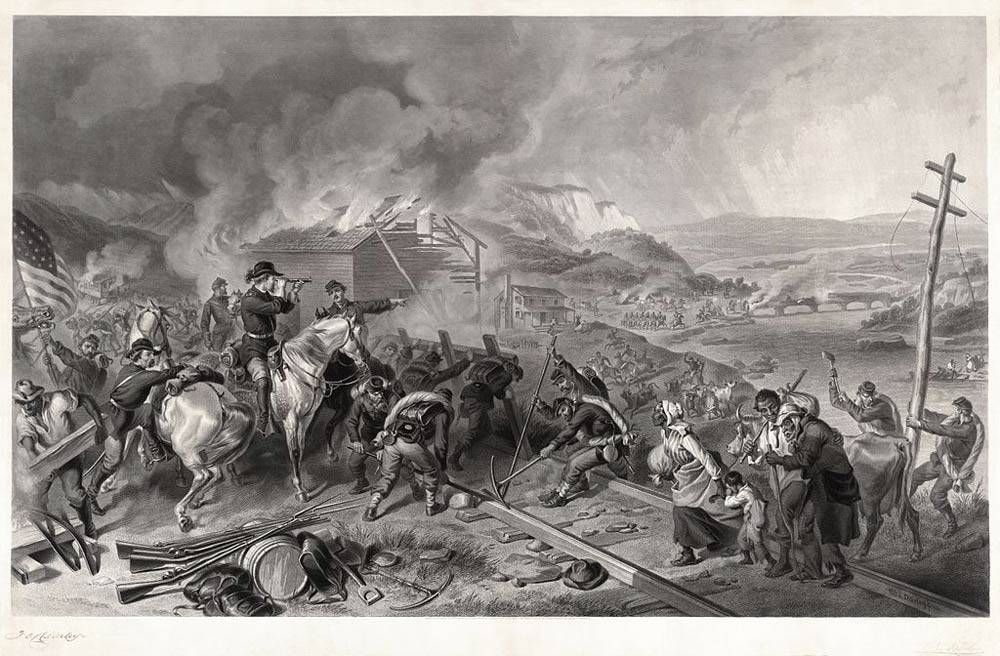

The March left the Southerners frightened and appalled. Sherman and his army had destroyed crops and fences, killed many livestock, and burned factories, houses as well as barns. This left the civilians demoralized and hungry. However, the forces refrained from killing civilians and raping women. Due to the hardships on children and women, desertions started to increase in Confederate R. Lee’s troops in Virginia. Sherman thought that his crusade against civilians would reduce the war period by breaking the Confederate willpower to fight.

At the end of Sherman’s March to the sea, his army of 60,000 men had covered 285 miles within 5 weeks. They had cut a swath of between 20 and 60 miles through Georgia. Sherman got the permission to continue with the psychological war into South Carolina in 1865. His march through Georgia to South Carolina made him an idol in the North and an arch-villain in the South.