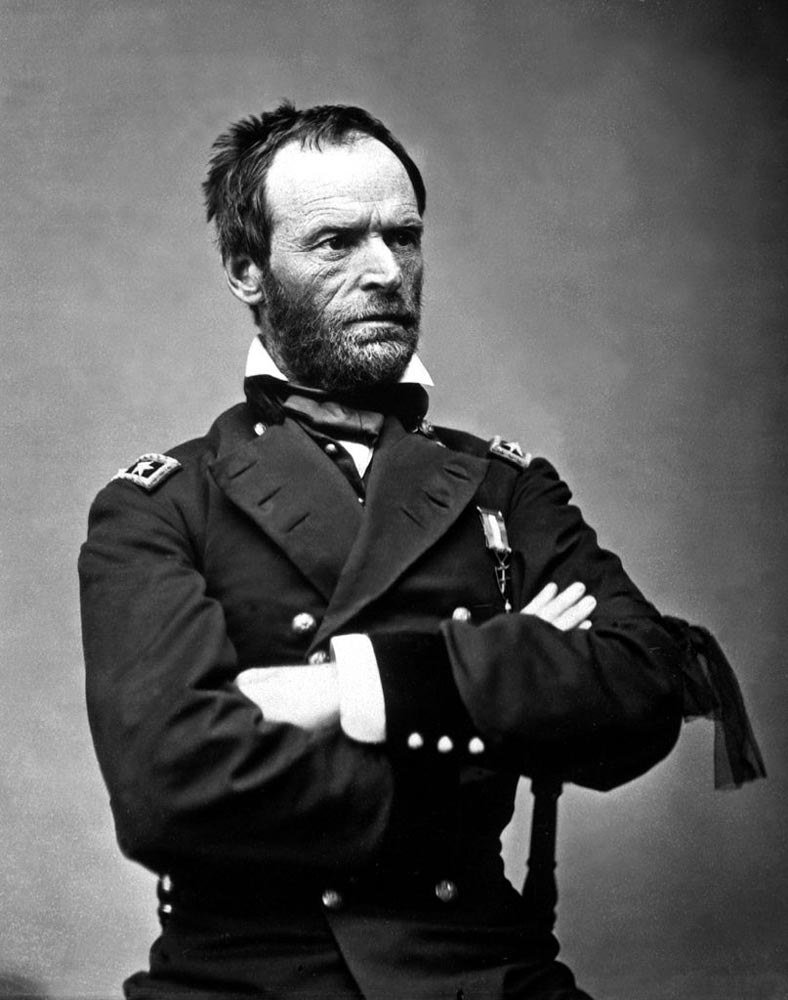

| William Tecumseh Sherman | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Feb. 8, 1820 Lancaster, Ohio |

| Died | Feb. 14, 1891 (at age 71) New York City |

| Allegiance | United States Army Union Army |

| Years | 1840–53, 1861–84 |

| Rank | Major General (Civil War), General of the Army of the United States (postbellum) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War First Battle of Bull Run Battle of Shiloh Vicksburg Campaign Jackson Expedition Chattanooga Campaign Meridian Campaign Atlanta Campaign Savannah Campaign (March to the Sea) Carolinas Campaign |

William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891) was a Union Army general during the Civil War, who was both praised for his superb grasp of strategic matters and criticized for what some saw as overly harsh treatment of the areas his troops invaded. He served under General Ulysses S. Grant in several major victorious campaigns, later succeeding Grant as the Western Theater commander. After the war was over, he remained a soldier, overseeing a number of Indian War campaigns. He is also remembered for his comment, “War is hell.”

Early Life

Sherman was born in the town of Lancaster, Ohio, a settlement which had not yet been incorporated as a city. His father, a well-known lawyer, died when he was only nine years old, after which he was sent away from home in order that he might be brought up by a friend of the family. After his childhood studies were complete, he was enrolled at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Here, his roommate was George H. Thomas who, like Sherman, would rise to generalship during the Civil War. Sherman was a popular student, but not considered among the finest of soldiers.

After graduation, Sherman, as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery, was sent to serve in Florida. He took part in the campaign against the Seminole Indians; this was his first experience of battle. A little later, like most of his contemporaries, he was posted to the Mexican-American War, although he remained in California throughout the period of hostilities and was never on the front line of a battle. He left the Army in 1853 to go to the gold-rush town of San Francisco, where he worked as a banker until the Panic of 1857 ruined much of the banking industry.

Civil War Service

After leaving San Franciso, Sherman traveled to Louisiana to become the head of one of the state’s new military academies, the Louisiana State Seminary. His tenure at the academy was rather short-lived, as the start of the Civil War was drawing closer. When war finally broke out, Sherman resigned from his job and returned north, enlisting as a colonel in the U.S. Army. He was not personally an abolitionist, but was strongly opposed to secession by Southern states, believing that the unity of the Union was crucial to maintaining it as a thriving nation.

After leaving San Franciso, Sherman traveled to Louisiana to become the head of one of the state’s new military academies, the Louisiana State Seminary. His tenure at the academy was rather short-lived, as the start of the Civil War was drawing closer. When war finally broke out, Sherman resigned from his job and returned north, enlisting as a colonel in the U.S. Army. He was not personally an abolitionist, but was strongly opposed to secession by Southern states, believing that the unity of the Union was crucial to maintaining it as a thriving nation.

At the First Battle of Bull Run in Virginia, the Confederacy scored a major victory over the Union forces. Sherman fought at this battle, and was then placed in command of an army in Kentucky. Here, his performance was rather unimpressive: he suffered from chronic nervousness in his actions and repeatedly asked for reinforcements. His behavior was considered so odd that elements of the press openly called him mad. His confidence only really returned when he was given clear and steady support by his new commander, who was none other than Grant.

During the fluctuating Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, Sherman and Grant began to form a close working relationship. On the first day of the battle, the Union forces were attacked without warning by Confederate troops, with the two commanders having to strive mightily in order to repel the enemy and simultaneously stop their own men from fleeing in panic. Sherman suffered a hand wound and twice had his horse shot from beneath him, but his conduct under these difficult conditions was exemplary. Grant was impressed by this, and the two men formed an effective team to push for victory for the Union.

Sherman and Total War

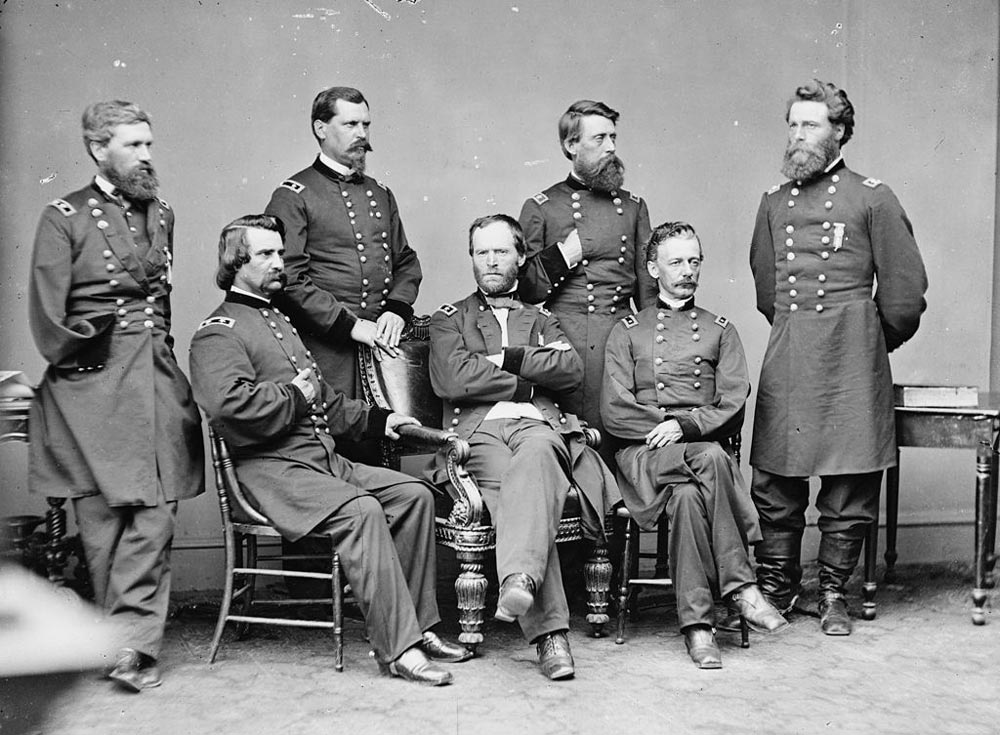

Perhaps Sherman’s most important victory in collaboration with Grant came at the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863. Here, the Confederacy’s hold over the Mississippi River, essential for the movement of men and supplies, was broken, an event which would have far-reaching consequences. After this triumph, Grant was made the Union Army’s overall commander by President Lincoln and departed for Washington. Sherman was the man who was made commander of the Mississippi division in Grant’s place.

Perhaps Sherman’s most important victory in collaboration with Grant came at the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863. Here, the Confederacy’s hold over the Mississippi River, essential for the movement of men and supplies, was broken, an event which would have far-reaching consequences. After this triumph, Grant was made the Union Army’s overall commander by President Lincoln and departed for Washington. Sherman was the man who was made commander of the Mississippi division in Grant’s place.

In the middle of the following year, Sherman and his men set out on a push eastward which took them through Georgia. This, if successful, would effectively end the South’s chances of forcing a victory in the war as a whole. Grant, still in overall control of the Union forces, realized that the essential factor was the Confederates’ willingness to fight to the end: to achieve victory, their will would have to be broken. Sherman was ordered to carry out what, in later years, would come to be known as “total war”, in that he was given license to destroy anything in his path.

September 1864 saw Sherman’s army capture Atlanta, setting fire to a large number of the city’s buildings including its crucial military stockpiles. Once this was done, he turned toward the Atlantic, taking the city of Savannah in the process, before moving north once more into South Carolina. In both this state and neighboring North Carolina, Sherman continued the “total war” policy: military assets such as bridges and railroads were destroyed, but so were farms and their livestock, and even private homes. Sherman had reached Raleigh, a trail of devastation in their wake, by April 9, 1865, when the final Confederate surrender came.

After the War

In 1869, Grant was elected as President of the United States, and he wasted no time in selecting Sherman, his trusted friend, as the U.S. Army’s general commander. In this role, Sherman headed up a number of campaigns against Western Indian tribes, which were carried out with studied brutality. His aim was the same as it had been against the Confederacy: to break the Indians’ spirit to resist and to leave their lands too barren for them to survive. Sherman felt that the Indians formed an obstacle to American progress and that extermination would probably be required, though he was opposed to corruption within the ranks of the government agents who oversaw Indian reservations.

In 1869, Grant was elected as President of the United States, and he wasted no time in selecting Sherman, his trusted friend, as the U.S. Army’s general commander. In this role, Sherman headed up a number of campaigns against Western Indian tribes, which were carried out with studied brutality. His aim was the same as it had been against the Confederacy: to break the Indians’ spirit to resist and to leave their lands too barren for them to survive. Sherman felt that the Indians formed an obstacle to American progress and that extermination would probably be required, though he was opposed to corruption within the ranks of the government agents who oversaw Indian reservations.

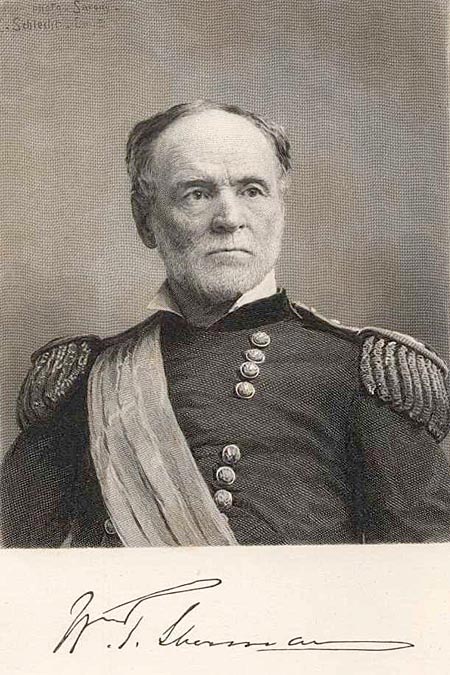

Sherman left the Army in 1884 and lived in New York City for much of the remainder of his life, becoming a patron of the arts and a popular speaker at events such as formal dinners. When asked to run for President for the Republicans in 1884, he refused in forceful terms, making the famous statement that he would not accept if nominated and would not serve if elected. Sherman died in 1891, and was buried in St. Louis. The Sherman tank used by the U.S. Army in World War Two and the enormous “General Sherman” sequoia tree in California are named in his honor.