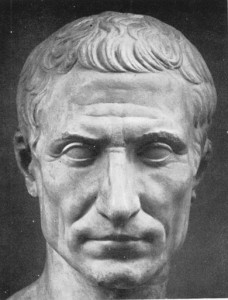

Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) was a Roman general, whose increasing power in the middle of the first century B.C. played an important role in the ending of the Roman Republic. Despite his military genius and many victories, he made powerful enemies in the Senate, and he was eventually assassinated. His heir, Octavian, rose to become the first Roman Emperor. Caesar himself wrote extensively about his career, and his “Commentaries on the Gallic Wars” remained a standard text for centuries to come.

Early Life

Julius Caesar was born in Rome in 100 B.C., in the month that was later to be named July in his honor. His family were influential patricians, and Caesar followed the set path for boys of his background when becoming an army officer. He quickly proved himself to be highly skilled at swordplay, as well as an expert rider.

Despite his young age, he also showed a gift for inspiring the men he commanded, some of whom were much older and more experienced in battle. He also increased morale by doubling his soldiers’ wages.

At age 25, Caesar fell into the hands of pirates, who decided to ransom him rather than slit his throat. The money was paid by his family, but Caesar found the humiliation of having been captured intolerable to bear. He gathered a group of his friends and tracked down the pirates, killing them all by crucifixion. He then turned his attention to a political career, putting himself into debt by putting on games. His gamble paid off, and he was elected as consul in 59 B.C.

Caesar in Power

As consul, he wasted no time in demonstrating the importance he attached to the military, going to the Public Assembly in order to push through a bill, giving land to ex-soldiers that had been rejected by the Senate. Caesar was impatient with his opponents, going so far as to pay thugs to rough up senators who opposed him. This brought him enemies within the senatorial ranks. Nevertheless, after his consulship Caesar was sent to command the army in Narbonese Gaul.

As consul, he wasted no time in demonstrating the importance he attached to the military, going to the Public Assembly in order to push through a bill, giving land to ex-soldiers that had been rejected by the Senate. Caesar was impatient with his opponents, going so far as to pay thugs to rough up senators who opposed him. This brought him enemies within the senatorial ranks. Nevertheless, after his consulship Caesar was sent to command the army in Narbonese Gaul.

The Gaulish cavalry was highly skilled and won some victories over the Romans, but Caesar felt that their inter-tribal rivalries would allow the better organized Romans to triumph in the long run. By 55 B.C. he proved this. His forces had destroyed many of the Gauls, as well as the Helvetii in the Alps.

Once he reached the north coast of Gaul, Caesar resolved that his next assault would be on Britain. Although his invasion did not result in the addition of Britain to the Empire, he was by now a rich man, thanks to the riches he had taken in Gaul.

Caesar was anxious that his successes should be widely known, so he published accounts of his campaigns in Rome. The Senate, unhappy with his immense popularity, gave control to Pompey, a rival soldier, and resolved that Caesar must retire. The latter refused to yield and marched on Rome itself.

In 48 B.C., at the Battle of Corfinium, Caesar beat a force of Senate loyalists, and the news of his victory resulted in the flight of his enemies from the capital. He is said to have pardoned all his domestic enemies when he returned to Rome.

Caesar in Egypt

Pompey retreated to still-loyal Macedonia but was then forced to flee to Egypt, pursued by Caesar’s superior army. The Egyptian ruler, Ptolemy XIII, was worried that this would lead to a Roman invasion of Egypt and had Pompey killed, intending to send his head to Caesar as proof. Two days later, Caesar entered Alexandria and was given the head, but the gesture backfired: he was shocked by Ptolemy’s violent act and seized the city himself, intending to demand money to return to Rome.

Pompey retreated to still-loyal Macedonia but was then forced to flee to Egypt, pursued by Caesar’s superior army. The Egyptian ruler, Ptolemy XIII, was worried that this would lead to a Roman invasion of Egypt and had Pompey killed, intending to send his head to Caesar as proof. Two days later, Caesar entered Alexandria and was given the head, but the gesture backfired: he was shocked by Ptolemy’s violent act and seized the city himself, intending to demand money to return to Rome.

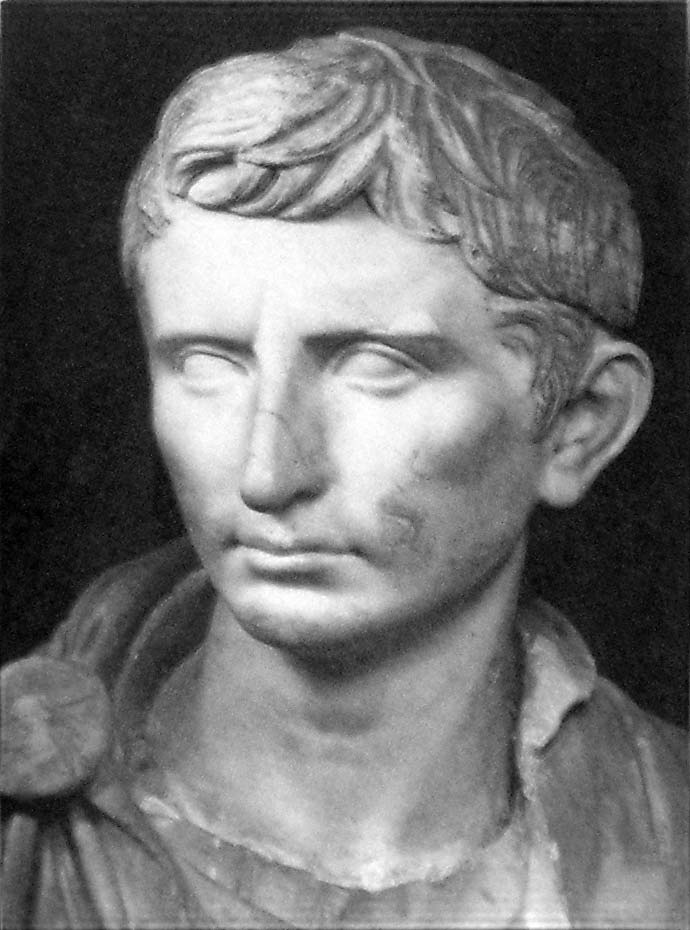

During this period, however, Caesar met Egypt’s young queen, Cleopatra. Although Caesar was now over 50 and had three marriages behind him, he became besotted with Cleopatra and – after defeating Ptolemy – installed her as ruler with her brother, also called Ptolemy. In June 47 B.C., Cleopatra’s son was born; he was nicknamed Caesarion in tribute to his father. Although Cleopatra wanted her son to be named as her lover’s heir, Caesar chose instead to give the honor to Octavian, his nephew.

In 46 B.C., Cleopatra and her sons visited Rome. Many senators disliked their relationship, partly because Caesar was already married and partly on account of her nationality. Caesar tried to win back the whole-hearted support of the ordinary people by launching an expansionist push against the Parthians. Many in Rome were uneasy at his ambition, feeling that it was better to consolidate Rome’s existing territories, rather than attempting to increase their size still further.

The Return to Rome

Back in the Roman capital, Caesar appointed 300 senators who were known to be loyal to him. This saw the effective end of the Senate as an independent law-making body: although it – and the Public Assembly – continued, it was Caesar who was now in total control. By 44 B.C., his power had risen to such heights that he felt sufficiently confident to declare himself Dictator for life. The role of Dictator had previously only been used sparingly, temporarily, and in the direst of emergencies.

Caesar had a number of fine buildings constructed in honor of himself and his family, and huge numbers of sculptures of Caesar were distributed around the Empire. He courted further controversy when some of these statues carried the claim that Caesar was a living god.

The people of Rome started to become concerned that Caesar hoped for a return to the time of Roman kings, something underlined when he took to wearing red boots made in the royal style and imaging his head on coins; no living Roman had ever appeared on a coin before.

Plot and Assassination

Although Caesar had once been enormously popular, by now many people objected to what they saw as his desire to be king, and to his habit of rejecting advice. Dissension grew to the point where a band of senators agreed that Caesar would have to be killed. This group, numbering around 60 men, included some who had formerly been among Caesar’s closest friends. Most famously, these included Marcus Brutus, who was thought by many to be one of Caesar’s illegitimate children.

Although Caesar had once been enormously popular, by now many people objected to what they saw as his desire to be king, and to his habit of rejecting advice. Dissension grew to the point where a band of senators agreed that Caesar would have to be killed. This group, numbering around 60 men, included some who had formerly been among Caesar’s closest friends. Most famously, these included Marcus Brutus, who was thought by many to be one of Caesar’s illegitimate children.

Since Caesar was about to leave for Parthia, it was necessary for the plotters to hurry, and the assassination was arranged for March 15, 44 B.C. – three days before his departure.

As Caesar arrived at the Senate, he was surrounded by the conspirators and was stabbed by Casca. When Caesar turned, hoping for assistance, he saw the others with their daggers drawn and realized he was to die. Upon seeing Brutus among them, and so realizing the situation was hopeless, Caesar awaited his fate. Later he would come to be revered as one of the finest military commanders of the ancient world.