| Georgia O’Keeffe Famous Paintings | |

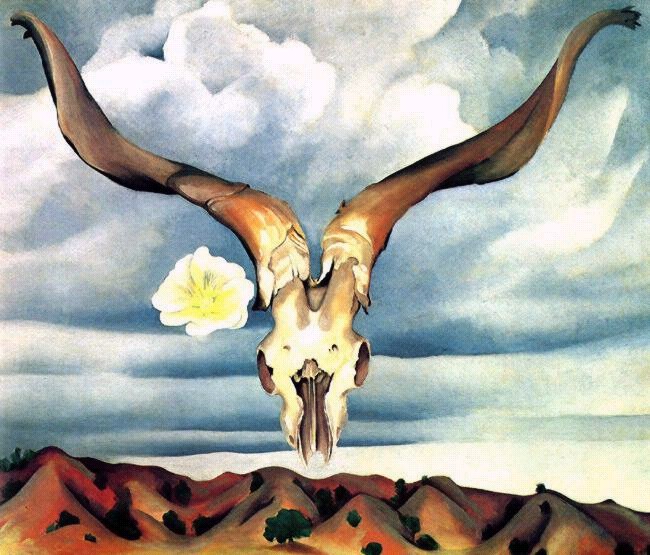

| Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue, 1931 | |

| Blue and Green Music, 1919-1921 | |

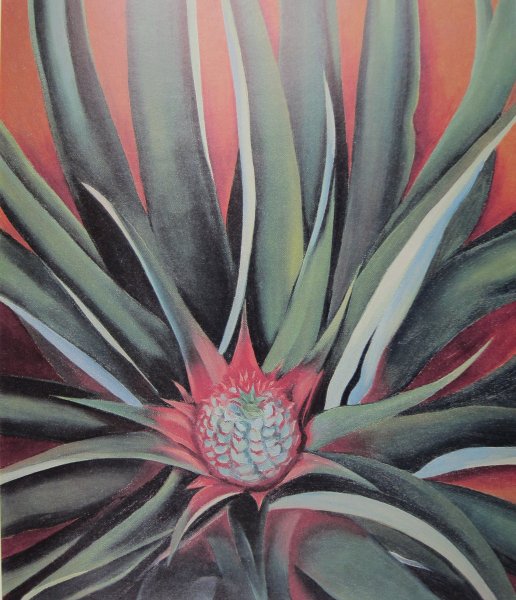

| Pineapple Bud, 1939 | |

| Black Iris, 1926 | |

| Red Canna, 1924 | |

| Blue Morning Glories, 1938 | |

| Complete Works |

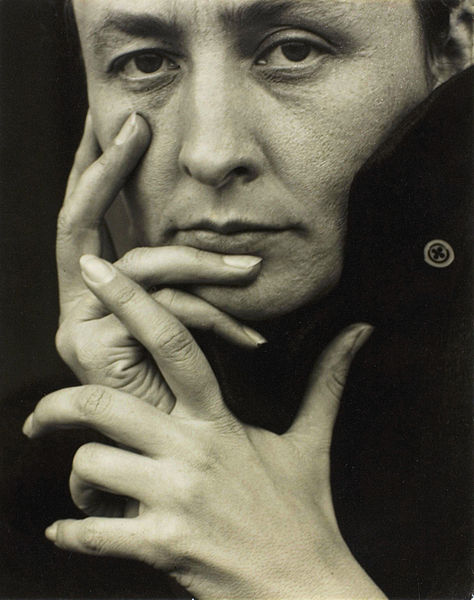

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, on November 15, 1887. She was the second out of seven children and the first girl in her family. Her father was Hungarian, and her mother was a descendant of one of many who came on the Mayflower. Since her mother loved art, she had all the children take art classes. Georgia was the only one she considered to be good at art and was encouraged to take additional classes from the Town Hall, where a local water color painter gave lessons.

In 1901, her family moved to Williamsburg, Virginia, so the eldest could attend college. Georgia had hoped to attend high school in Wisconsin, so lived with her aunt. She was reunited with her family in 1903, and completed high school in Virginia so her family could see her graduate.

Instead of going to college back east like her mother wanted, she attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1905. She then moved to New York City in 1907, and then began going to the Art Students League. After being there one year, she won the William Merritt Chase Award for her oil painting Mona Shehab (Dead Rabbit on a Copper Pot), which was a still life, and considered to be the best painting of the year at the school.

Shortly after, she moved back to Chicago and started working as an illustrator. She quit painting during this time, her family was going through financial trouble, and she realized she could not make a decent living from selling her art.

In 1910, she moved back to Virginia because she had contracted the measles. She stayed with her family until 1912, when she decided to attend a seminar on art, she was so inspired by it that she went back to painting. Georgia attended a Rodin exhibit, and there she met Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer. He offered her a room at his niece’s home which allowed her move out of her parents’ house.

By July of 1913, she and Alfred were so deeply in love; he left his wife and moved in with her. Finally, in 1924, his divorce became final. He and Georgia married. That same year, Georgia’s first flower painting came out, Petunia, No. 2, and it was a success; she continued to paint more flowers.

By July of 1913, she and Alfred were so deeply in love; he left his wife and moved in with her. Finally, in 1924, his divorce became final. He and Georgia married. That same year, Georgia’s first flower painting came out, Petunia, No. 2, and it was a success; she continued to paint more flowers.

Beginning in 1923, Alfred hosted an annual exhibit of her work, which was widely accepted and attended by all the art critics. Five years later, she sold six of her Calla Lily paintings for $25,000, which at that time was the most expensive piece of art sold at an auction.

She later took a trip to New Mexico with a friend, and fell in love with the place. From 1929 to 1949, she spent almost every year painting and living there, except for 1933-1934. During this period, she became very ill, and had to be taken to a hospital. It is unclear whether or not she had a nervous breakdown, but she was treated for psychoneurosis.

When she was released from the hospital, she went for a trip to northern New Mexico, and bought some property called Ghost Ranch. She lived there from that day on, and her paintings started to reflect the western/Mexican culture around her. Cow skulls started appearing in her art, juxtaposed with flowers from the area, with a desert landscape in the back ground.

In 1942, she was given a one-woman retrospective, which is when a museum dedicates an entire exhibit to one artist. She received a second in 1946, and was very proud of her achievements. But towards the end of 1946, her husband Alfred died. She went to New York to tidy up her husband’s affairs, and then permanently moved back to New Mexico.

In 1962, she was inducted to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. At the time, there were only fifty seats open, and it was considered a very big honor to be part of this organization. Its goal was to “foster, assist, and sustain excellence in all fields of art.” In 1970, the feminist movement started, and O’Keeffe’s paintings were used as examples of feminism in art, which made her furious. Her intent in all her art work was to closely scrutinize things, not to make flowers into sexual objects like they were claiming.

The next year, her eyesight began to fail. Her center vision was rapidly disappearing, and all she could really see out of was her peripheral vision. She quit painting again, she did not want to ask for assistance with her art. On July 10, 1977, President Gerald R. Ford gave her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor an American can earn besides a Purple Heart.

Since she could no longer take care of herself, she moved to Santa Fe where she could receive help. She became increasingly frail over the next few years, and she started painting again to help pass the time. On March 6, 1986, she died at the grand old age of 98. She was cremated the next day, which was stated in her will, and her ashes were dumped on Pedernal Mountain, which was visible from her balcony at Ghost Ranch.