| United States Constitution | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The U.S. Constitution | |

| Preamble | |

| Articles of the Constitution | |

| I ‣ II ‣ III ‣ IV ‣ V ‣ VI ‣ VII | |

| Amendments to the Constitution | |

| Bill of Rights | |

| I ‣ II ‣ III ‣ IV ‣ V ‣ VI ‣ VII ‣ VIII ‣ IX ‣ X | |

| Additional Amendments | |

| XI ‣ XII ‣ XIII ‣ XIV ‣ XV ‣ XVI ‣ XVII ‣ XVIII ‣ XIX ‣ XX ‣ XXI ‣ XXII ‣ XXIII ‣ XXIV ‣ XXV ‣ XXVI ‣ XXVII | |

| View the Full Text | |

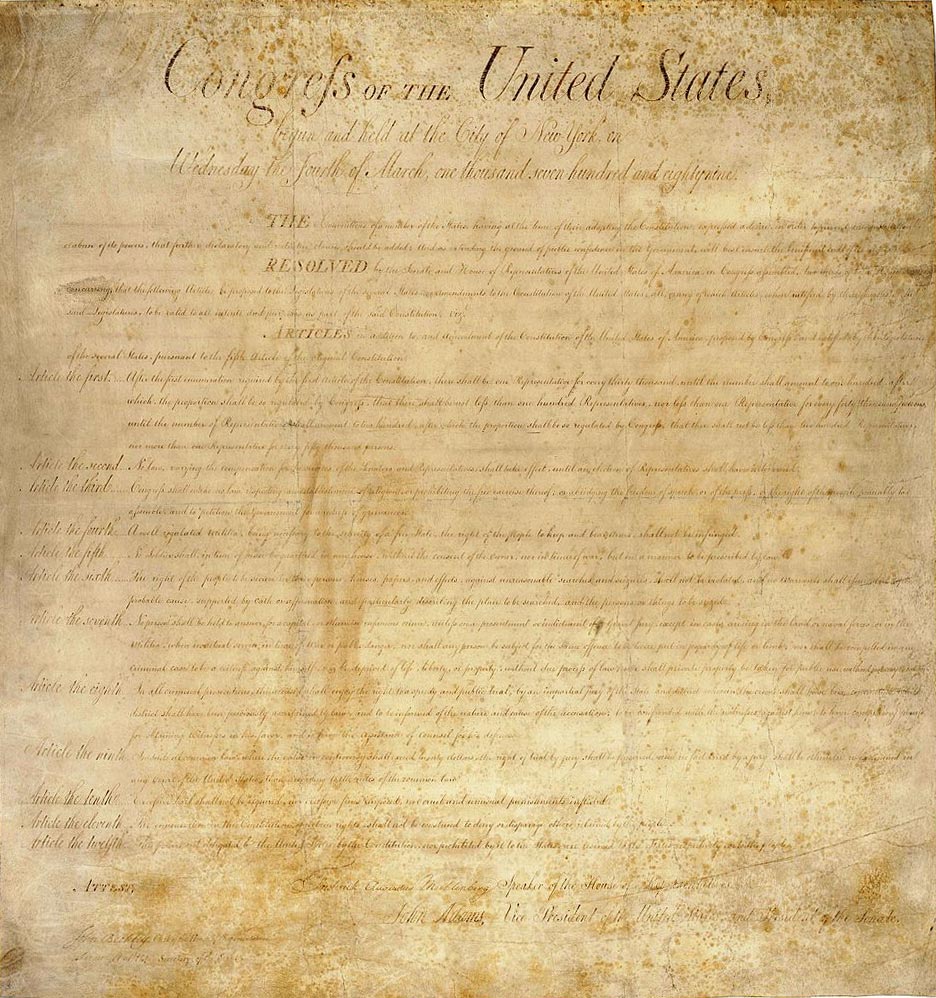

| Original Constitution | |

| Bill of Rights | |

| Additional Amendments |

The 8th Amendment to the United States Constitution forms part of the Bill of Rights and became law in 1791. Its most notable feature is that it bars the United States government from subjecting any citizen to cruel and unusual punishment. Other parts of the amendment prohibit the government from imposing fines or bail which are considered excessive.

Text

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Historical Background

Several of the concepts used in this amendment, as well as a considerable number of its most significant words and phrases, date back to the Bill of Rights passed in England in 1689. This has come about after the case of Titus Oates, whose lies under oath had led to the execution of a number of innocent people. Oates was sentenced to whipping and the pillory, rather than to death, because it was thought that executing him would make honest people fear to give evidence in court.

The phrase “cruel and unusual punishment” was first used in America in 1776, in Virginia’s Declaration of Rights. When the United States Constitution was ratified in 1788, it was recommended by the Virginia convention that the same language should be incorporated into the U.S. document. Patrick Henry and George Mason, among other Virginians, intended that the restriction should also bind Congress, since otherwise, that body could simply inflict cruel punishments rather than them being imposed by the courts.

Their other main line of argument was that, without a provision of this sort, Congress might replace the common law which the U.S. had largely inherited from Britain, and replace it with civil law of the type practiced in countries such as Spain and France. Henry, in particular, was anxious to show that the ancestors Americans should revere would not have allowed torture and barbarity to exist in their lands. The controversy over the issue was substantial, but the 8th Amendment went before Congress in 1789 and was adopted two years later.

Their other main line of argument was that, without a provision of this sort, Congress might replace the common law which the U.S. had largely inherited from Britain, and replace it with civil law of the type practiced in countries such as Spain and France. Henry, in particular, was anxious to show that the ancestors Americans should revere would not have allowed torture and barbarity to exist in their lands. The controversy over the issue was substantial, but the 8th Amendment went before Congress in 1789 and was adopted two years later.

Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Under the terms of the 8th Amendment, as interpreted by the United States Supreme Court, certain punishments are considered barbaric by definition and are therefore prohibited in all circumstances. These include disembowelment and burning alive. In the 21st century, the Supreme Court has extended this prohibition to cover the execution of those below 18 years of age and of those who suffer from a mental handicap. These more recent extensions were the subject of bitter debate and proved highly controversial.

The Supreme Court has also ruled that other punishments should be considered cruel and unusual under specific circumstances. In particular, the Court has said that a principle of proportionality must be adhered to. The 1958 case of Trop vs. Dulles established that the removal of a person’s U.S. citizenship was unconstitutional, on the grounds that it meant that person’s “total destruction” as a member of society. In 1972, also, Furman vs. Georgia effectively outlawed the use of capital punishment in the U.S., although Gregg vs. Georgia four years later allowed executions to resume.

Another significant ruling regarding the reach of the 8th Amendment came in 1977, when in the case of Coker vs. Georgia, the Supreme Court found that it was unconstitutional – on the grounds of a lack of proportionality – for those found guilty of the crime of rape, where the victim was not killed, to be sentenced to death. The minority in this case delivered a furious dissenting opinion, branding the majority “myopic” in that they had failed to take account of the broad sweep of American legal history, rather than simply looking at cases from the previous few years.

Other Provisions

The 8th Amendment’s prohibition on excessive fines was seen as something of a curiosity in the modern era, until the case of United States vs. Bajakajian in 1998. The man in question had taken more than the maximum permitted $10,000 of U.S. currency out of the country without reporting it as the law required, and was fined over $350,000 as a result. The Supreme Court ruled that this fine was so disproportionate that it went against the amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause. This was the first time in over two hundred years of the 8th Amendment’s existence that this clause had been found to have been violated.

The amendment’s Bail Clause came about as a result of injustices perpetrated in England, where judges often abused their power in determining whether bail should be allowed to suspects. After a number of unsuccessful attempts at reforming the law, the English Bill of Rights in 1689 specifically outlawed excessive bail, although it did not specify precisely which offenses should or should not qualify as bailable. The U.S. Supreme Court held in 1987 that the 8th Amendment’s bail clause had only one meaning: that bail conditions, when compared with the magnitude of the alleged crime, should not be excessive.