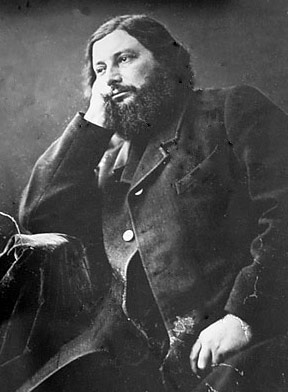

| Gustave Courbet | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 10, 1819 Ornans, Doubs, France |

| Died | Dec. 31, 1877 (at age 58) La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland |

| Nationality | French |

| Movement | Realism |

| Field | Painting, Sculpting |

| Works | View Complete Works |

French painter Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) was influential in leading the Realist movement of 19th century French painting. Realism as applied to the visual arts refers to a style that describes the simple fact of what the eyes can observe, as opposed to romanticism which was a style that dominated the French art world of the time, and was underscored by strong emotion such as trepidation, terror, or awe. In contrast, the Realist of 19th century France abandoned the overstated emotionalism which was depicted in much of the artwork of that time period, and instead focused on painting subjects that were considered uncouth, such as peasants and the working poor. Gustave Courbet holds a significant place in 19th century French art history as a trend setter, and as a painter who was unafraid to make controversial cultural commentary with his artwork.

Early Life And Rising Influence

Courbet was born Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet in 1819 to a successful farming family in Ornans, France. Although the family was relatively affluent, anti-monarchical sentiments prevailed in the family since his grandfather fought in the French Revolution. At a young age, Courbet’s sisters, Zoé, Zélie and Juliette, were his primary figures for sketching and painting, and as a young man of twenty, Courbet moved to Paris in 1839 to work in the art studio of Steuben and Hesse. But having an independent mindset, he soon left, electing instead to cultivate his very own technique and style by analyzing the paintings of Spanish, Flemish and French masters in the Louvre, and then painting replications of these artworks. After moving to Paris, Courbet would often return home to Ornans to hunt, fish, and search within himself for artistic creativity.

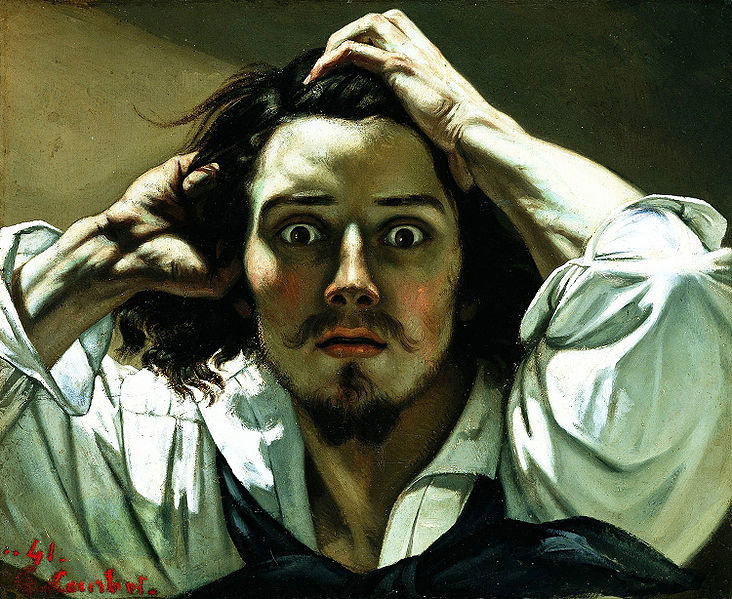

Courbet’s first artworks include a painting of an Odalisque (a female slave in the Ottoman Empire) which was inspired by the writings of Victor Hugo, and a Lélia illustration of French writer George Sand. But he quickly departed from literary influences, preferring instead to structure his works of art on witnessed realism. Although Courbet’s underlying desire was to portray the world of reality, many of his self-portraits of the 1840s are Romantic in nature. Examples include, Self-Portrait with Black Dog (approved for display at the 1844 Paris Salon), The Sculptor (completed in 1844), the exaggerated self-portrait called Desperate Man (completed in 1845), The Cellist a Self-Portrait (shown at the 1848 Paris Salon), and The Man with a Pipe (finished in 1849).

Courbet’s first artworks include a painting of an Odalisque (a female slave in the Ottoman Empire) which was inspired by the writings of Victor Hugo, and a Lélia illustration of French writer George Sand. But he quickly departed from literary influences, preferring instead to structure his works of art on witnessed realism. Although Courbet’s underlying desire was to portray the world of reality, many of his self-portraits of the 1840s are Romantic in nature. Examples include, Self-Portrait with Black Dog (approved for display at the 1844 Paris Salon), The Sculptor (completed in 1844), the exaggerated self-portrait called Desperate Man (completed in 1845), The Cellist a Self-Portrait (shown at the 1848 Paris Salon), and The Man with a Pipe (finished in 1849).

In 1846 and 1847 Courbet made several trips to the Netherlands and Belgium which served to cement his belief that artists ought to depict the true life surrounding them, as Frans Hals, Rembrandt van Rijn, and other Dutch Master had. As a result of his beliefs and his growing influence, by 1848 Courbet had gathered supporters among many Neo-romantics of the time, and especially Realists and most importantly, the French art critic, Champfleury.

Courbet achieved more widespread recognition when his painting After Dinner at Ornans received a prestigious gold medal at the 1849 Paris Salon and was bought by the state. The gold medal ensured that his paintings would no longer need jury endorsement for exhibition at the Salon, a luxury that he enjoyed until the rule was change in 1857. Also in 1849, Courbet painted Stone-Breakers, what many call the first of his great artworks. The painting depicts roadside peasants breaking and carrying rocks, and was sadly destroyed in the British bombing of Dresden in World War Two.

Establishing And Securing Influence

With the Salon of 1850-1851, Courbet expanded his realistic art influence by submitting several paintings including the Peasants of Flagey, The Stone Breakers, and A Burial at Ornans. A Burial at Ornans is one of Courbet’s most significant paintings, and captures the funeral of his grand uncle which was held in September 1848. The townspeople who were present at the funeral were the actual models for the painting. Traditionally, models had always been used by artists as subjects in historical artwork. However in Burial at Ornans, Courbet used the real people who attended the burial. The resulting depiction is a realistic display of them, and of existence in Ornans.

With the Salon of 1850-1851, Courbet expanded his realistic art influence by submitting several paintings including the Peasants of Flagey, The Stone Breakers, and A Burial at Ornans. A Burial at Ornans is one of Courbet’s most significant paintings, and captures the funeral of his grand uncle which was held in September 1848. The townspeople who were present at the funeral were the actual models for the painting. Traditionally, models had always been used by artists as subjects in historical artwork. However in Burial at Ornans, Courbet used the real people who attended the burial. The resulting depiction is a realistic display of them, and of existence in Ornans.

The painting is large, measuring 10 feet by 22 feet, and simultaneously drew both positive reviews and intense condemnation from critics as well as the public. This may have been partly because it disrupted traditional ideas by showing a commonplace burial with a scope, which in the past would only have been set aside for a highly religious ceremony, or royal and elevated subject. As a result of A Burial at Ornans Courbet certainly gained more notoriety, and eventually the public warmed to the idea of this new Realist style of painting. The importance of A Burial at Ornans was not lost on Courbet also, as he likened the Burial depiction to a burial of the Romantic style of painting itself.

After this, Courbet became somewhat of a celebrity, and the words “genius,” “socialist,” and “savage” were used to describe him. Associating his ideas of realism to political insurrection, Courbet actively promoted democratic and socialist ideas, and spanning the early 1850s, he painted several works using common folks to highlight his political ideology such as, Village Damsels (1852), Wrestlers (1853), Bathers (1853), The Sleeping Spinner (1853), and The Wheat Sifters (1854).

Throughout the latter part of the 1850s, Courbet continued to paint and display his works for which he became increasingly famous. In the 1857 at the Salon, he submitted six paintings, including the shocking (for the time period) Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Summer), which showed two prostitutes under a tree. Courbet began painting a string of progressively sexual artworks including Femme nue couchée. This series was crowned by The Origin of the World in 1866 which shows a woman’s genitals, and was not publicly displayed until 1988, and Sleep (in 1866), showcasing two women in bed. By exhibiting these sorts of scandalous and controversial paintings, Courbet assured himself public recognition and sales of his work.

In 1870 Courbet was nominated by Napoleon III for the Legion of Honor which is the highest decoration in France. But true to his anti-authoritarian ideals, Courbet refused to accept the honor which not only angered the upper power structure but earned him immense popularity from those that were against the Napoleon regime. When the Paris Commune took power in France in 1871, Courbet was put in charge of all of the Paris art museums, and is credited with saving them from looting mobs. However, the Paris Commune was not stable and power shifted back to the old guard government shortly thereafter, leaving Courbet in an untenable political situation.

Exile And Death

When the Paris Commune assumed control of France in 1871 (March 18 – May 28), Courbet proposed that the Vendôme Column (a military commemoration built by Napoleon I) be taken down. He argued it was a monument devoid of all artistic value, and proposed that it be moved to the Hôtel des Invalides. His proposal was taken up by the Paris Commune and it was disassembled, with no intentions of being rebuilt. With the short life of the Paris Commune in power, and for his part in executing the order for dismantling the Vendôme Column, Courbet was held responsible by a Versailles court martial in September 1871, and sentenced to six month in prison and a fine of 500 francs. He continued to paint even while in prison, completing several still life compositions.

When the decision was made in 1873 by newly elected president Mac-Mahon to rebuild the Vendôme Column, Courbet was ordered to pay the expenses required for the Column’s reconstruction. He was unable to pay the high cost of rebuilding the Column, so he went into exile in Switzerland to avoid bankruptcy. Over the next four years until his death, Courbet continued to paint and participated in a few regional and national exhibitions. On 31 December 1877 Gustave Courbet, leader of the Realist movement of painting in 19th century French art, died in the municipality of La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, of a liver disease.