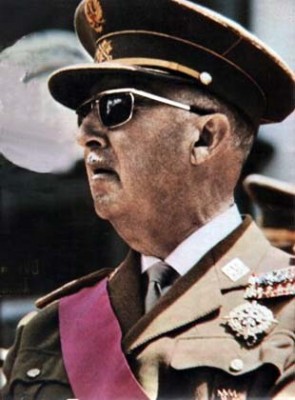

Francisco Franco was a Spanish military general who became Spain’s leader near the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939. His dictatorship lasted until his death in November 1975. The legacy of his regime is marred by appalling breaches of human rights and the murders of many thousands of civilians.

In modern Spain, all state owned statuary and commemorative plaques dedicated to Franco have been removed. Any private institutions that continue to display Franco commemorative material are unable to receive state aid. All streets and areas named in honor of Franco have been renamed.

Early years

Franco was born in Ferrol, Spain in 1892. Several generations of his family on his father’s side had built successful careers in the Spanish naval service. Franco’s father wanted his son to keep up the family naval tradition, but due to an embargo on recruitment into the naval academy, Franco decided to join the army in 1907.

Africa

Franco graduated as a lieutenant in 1910. After serving in mainland Spain for two years he was sent to Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Morocco, in 1912. The Spanish were engaged in an ongoing, and often bloody, war with Moroccans who resented the Spanish presence in Melilla.

Franco graduated as a lieutenant in 1910. After serving in mainland Spain for two years he was sent to Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Morocco, in 1912. The Spanish were engaged in an ongoing, and often bloody, war with Moroccans who resented the Spanish presence in Melilla.

Franco quickly began to attract the attention of his commanding officers because of his capabilities as a soldier and leader. He was rapidly promoted and had attained the rank of captain before being severely wounded in battle. Following his recovery, he was made a major and returned to serve in mainland Spain in 1917.

When a new section of the army was established in 1920, Franco was appointed as second-in-command and returned to serve in Africa. He was soon promoted to lieutenant colonel. He then received another promotion following his leadership of a difficult mission to support troops in Melilla, after which he was placed in command of the Spanish Foreign Legion.

Shortly thereafter, he was promoted to full colonel. He was also involved in a decisive action against Rif forces in Morocco, which was to bring about the end of the Spanish Rif war. In 1925, Franco was promoted yet again, becoming the youngest Spaniard to be made a general.

In 1928, the separate training academies for various branches of the army were combined into a single academy, based in Zaragoza in Spain, and Franco was placed in charge of the institution.

During his rapid rise through the ranks, Franco had become friends with various members of the Spanish royal family. He was an avowed monarchist but did not express any opinion when the monarchy was ousted in 1931, and Spain was declared a republic.

Beginning of Franco’s Dissent

When the new republican government made the decision to close the general military academy, Franco was scathing in his attack on the decision. As a result, he was left without a commission for several months and was put under surveillance. In early 1932, he was transferred to serve in A Coruna, Spain and the following year he was moved to the Balearic Islands.

Following elections in October 1933, a number of revolutionary disturbances took place throughout Spain among groups who were opposed to the new government. Franco was appointed leader of the forces sent to suppress the rebels. The action against the rebels was successful, but was bloody with many casualties.

Franco openly expressed his opinions of the rebels as enemies of the state and declared that even though the rebels were Spanish, they should be treated just as if they were a foreign force. In May 1935, Franco was made Chief of General Staff.

Rebellion

Following another election in early 1936, which the left wing won by a narrow margin, tensions between the left and right were mounting. Franco was transferred to the Canary Islands, a Spanish-owned group of islands off of northwest Africa. Although this transfer was effectively an effort to remove him from a position of influence in the growing dispute, he initially voiced no opposition. He was approached by a group planning a coup but did not commit himself to supporting the action.

Nevertheless, the organizers decided to go ahead with the rebellion. When it was pointed out to Franco that he would have to make a choice about which side to support, he agreed to support the rising. The rebels arranged for Franco to be taken to Africa, where he was placed in charge of the Spanish African Army, and this became the first unit to rebel in July, 1936.

The coup failed to achieve an outright victory, but the rebels, who were now calling themselves the Nationalists, had taken control of about one third of the country, precipitating the start of the Spanish Civil War. The Nationalist side was supported by Italy and Germany, and with support from both of these countries, Franco was able to move a large force from Africa to Seville on the Spanish mainland, although his troops were blockaded in the city.

Franco appealed to Italy and Germany for additional support, especially for aircraft, and when he received this support he was able to break the blockade. Plans were then made to march on Madrid, and Franco dispatched a column of about 15,000 troops on this mission.

The column had reached Maqueda, just 50 miles from Madrid, when Franco ordered it to divert to Toledo, to lift a siege on Nationalist forces there. The column was successful in breaking the siege, but the delay gave the Republican side additional time to organize the defense of Madrid. When the Nationalists launched their first attack on Madrid in October, it was successfully repelled by Republican forces.

Before that occurred, and following the death of the Nationalist leader, General Jose Sanjurjo, the different Nationalist factions eventually made Franco commander in chief of the Nationalist forces. A key factor in this decision was that Hitler had declared that any help given by Germany would only go to Franco’s forces.

Head of State

At the beginning of October, a proclamation was issued by the Nationalists in Burgos in northern Spain. This declared that Franco was now the supreme commander of the Nationalist army and the Spanish head of State.

Rather than concentrating his troops on taking Madrid, Franco undertook a campaign of taking other cities and areas. Only when almost all of the rest of Spain was taken did Franco move to gain control in Madrid. Some historians and military analysts question the wisdom of that decision, believing that it prolonged the civil war. Both Hitler and Mussolini wanted a direct assault on Madrid, but continued to support Franco even though he ignored their advice.

On March 28th, 1939, the Nationalists finally succeeded in taking Madrid. The following day, the city of Valencia, which had been under attack by Nationalists for more than two years, also surrendered, and the Nationalists declared overall victory on April 1st.

Franco Regime

While atrocities had been committed by both sides during the war, those carried out by the Nationalists under Franco’s instructions had been the most extensive and the most brutal. For example, Franco had ordered his air force to attack a line of thousands of civilians who were fleeing from the city of Malaga in southern Spain.

Following his success, he undertook a campaign of brutal oppression against those who had sided with the Republican government during the civil war. The period immediately after the war become known as the White Terror. Nationalists executed many thousands of their opponents. Many more were imprisoned and others were placed into effective slavery.

The oppression was not confined to military and political opponents. Many people who had expressed opposition to the uprising were also targeted. Anybody who criticized the new leadership was at risk of being killed. Death squads roamed the country, slaughtering anybody they perceived to be against the new order. Thousands of people were taken from their homes, and were never seen again.

The war had led to a flood of refugees moving across the border into France. The French government confined them to refugee camps. Franco persuaded to French to encourage these people to return to Spain. Those who did were placed in concentration camps.

The Second World War

When the Second World War broke out, it was expected that Franco would join the Axis because of the support he had received from Italy and Germany during the civil war. Franco was somewhat ambivalent, and did not completely rule out support. He met with Hitler to discuss the possibility of Spain joining the Axis. He was willing to do so if Germany met several demands, but Hitler could not agree to these.

Despite officially maintaining that Spain was neutral, Franco did permit Spanish soldiers to join the German army, with the proviso that they would not be used on the western front.

Some historians think that Franco’s offer to support Germany, subject to Spanish demands being met, was a clever tactic. It showed that Hitler had nothing to fear from Spain, thereby removing Spain as a potential target for an Axis invasion. At the same time, Franco knew that Hitler would not be able to meet the demands, and Spain would not be drawn into the war.

In an effort to appease the Germans, Franco made Spanish ports available for German military operations. When it became obvious that Germany would be defeated, he withdrew this offer in 1943. During the war, Franco also entered into an agreement with the Germans to supply a list of Jews to them, and instructed local officials to draw up this list. However, he took no direct action against Jews, and none were forced to move to Axis occupied territories.

Post WWII

When the Second World War finished, Franco was officially recognized as the Spanish leader by a number of foreign governments, including Britain. In 1947, he declared that Spain was a monarchy, but did not reinstate any of the royals deposed in 1931. He left the throne vacant, but conducted himself, to all intents and purposes, as a King. This included having his likeness appear on coins, bank notes and postage stamps.

Within Spain, Franco set about installing an authoritarian regime. He banned trade unions, and introduced extensive censorship of all media. He also banned several political parties.

Spanish identity

Franco set about establishing a Spanish national identity, promoting culture like flamenco and bullfighting that he saw as intrinsically Spanish. However, Spain was made of a whole host of different cultural identities. In many parts of Spain, Spanish was not even the first spoken language. Franco banned the teaching of other regional languages such as Basque, and made it compulsory to use Castilian Spanish as the first language.

Additionally, any official or legal documents were only recognized if they were drafted in Castilian Spanish. All public buildings, road signs, and maps that bore names in regional languages were changed into Castilian.

The Catholic church

Franco also declared that the Catholic church was the established church of Spain. He put a ban on recruiting non-Catholics into state appointed roles. He reversed secular legislation brought in by the Republicans, and instituted bans on divorce, abortion and the use of contraceptives. He declared that civil marriages that had taken place under the Republicans were no longer recognized, and people in such unions had to remarry in church.

He established the quasi-military Guardia Civil. Although nominally a police force, the Guardia dressed in military-like uniforms. The force was widely regarded as Franco’s own personal police force, and was particularly feared.

Throughout his reign, Franco remained rigidly conservative and authoritarian, although enforcement of many of the laws, such as those dealing with speaking regional languages, was gradually relaxed.

Economy

Spain did enjoy some economic growth for a period under Franco. Much of this was brought about not by decisive government action but by other factors. Mass emigration had followed the civil war, and many of those emigrants were sending money back to relatives still in Spain. Spain established itself as a major tourist destination under Franco’s initiatives to develop infrastructure. Nevertheless, when he died, Spain was still one of the poorest countries in Europe.