| United States Constitution | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The U.S. Constitution | |

| Preamble | |

| Articles of the Constitution | |

| I ‣ II ‣ III ‣ IV ‣ V ‣ VI ‣ VII | |

| Amendments to the Constitution | |

| Bill of Rights | |

| I ‣ II ‣ III ‣ IV ‣ V ‣ VI ‣ VII ‣ VIII ‣ IX ‣ X | |

| Additional Amendments | |

| XI ‣ XII ‣ XIII ‣ XIV ‣ XV ‣ XVI ‣ XVII ‣ XVIII ‣ XIX ‣ XX ‣ XXI ‣ XXII ‣ XXIII ‣ XXIV ‣ XXV ‣ XXVI ‣ XXVII | |

| View the Full Text | |

| Original Constitution | |

| Bill of Rights | |

| Additional Amendments |

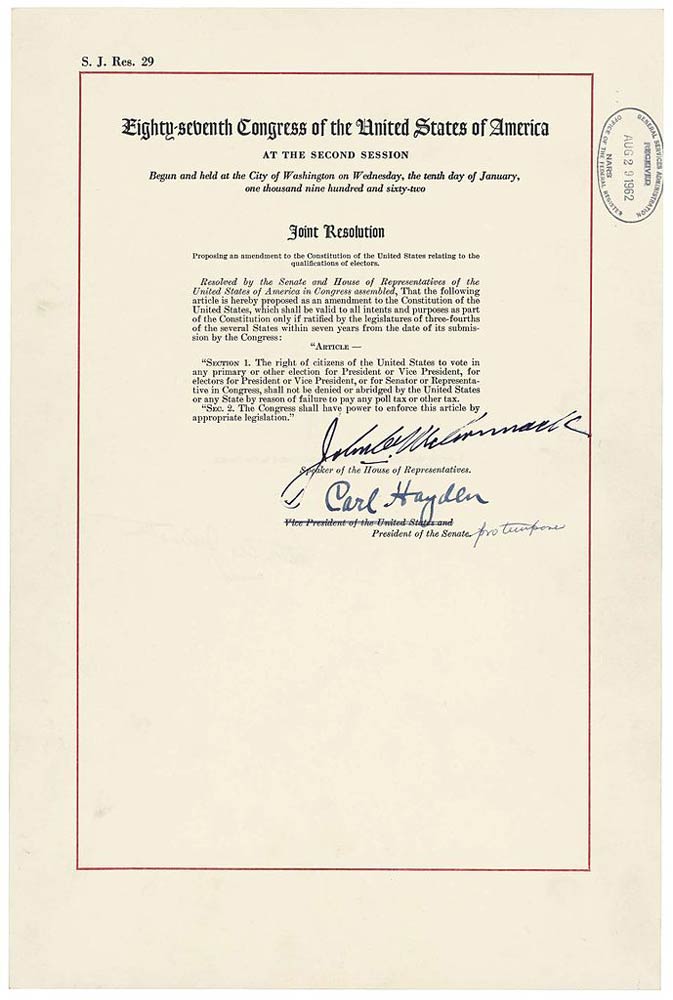

The Twenty-Fourth Amendment, ratified on January 23, 1964, eliminated the ability of governments, whether federal or state, to impose a poll tax or any other type of tax as a requirement for allowing citizens to vote.

Text

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.

Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Basis

After the dust had settled following the Civil War, and the Restoration Amendments had been passed, some southern states began the practice of charging a poll tax, the payment of which was required before a person would be allowed to vote. This afforded the ability to limit access to voting by African Americans, who could not pay the tax, yet did not violate the 15th Amendment. Poll taxes became a standard for voting in the South, eventually being implemented by all eleven states that once comprised the Confederacy.

Process

The road to ratification of the 24th Amendment was not an easy one, and it was not a short one. From the period spanning 1890 to the ratification of the amendment in 1964, it was considered, addressed, drafted, reconsidered, dropped, and reconsidered. The federal government, for the most part, disregarded the poll tax issue from the early 1900’s to 1937. Further, the poll tax even survived a challenge that was presented to the Supreme Court in which the tax was upheld as being part of states’ rights.

The road to ratification of the 24th Amendment was not an easy one, and it was not a short one. From the period spanning 1890 to the ratification of the amendment in 1964, it was considered, addressed, drafted, reconsidered, dropped, and reconsidered. The federal government, for the most part, disregarded the poll tax issue from the early 1900’s to 1937. Further, the poll tax even survived a challenge that was presented to the Supreme Court in which the tax was upheld as being part of states’ rights.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt vocalized his opinion that the poll taxes should be abolished but did not pursue the matter out of concern that doing so would alienate the conservative Democrats of the South. President Roosevelt was about to unveil his New Deal plan, and he needed those Democrats’ support.

Efforts to abolish the taxes continued despite efforts by some of the senior senators from the South to filibuster. In the late 1930’s, the House passed a bill 254-84 that would abolish the taxes; however, the senior senators were able to completely bring the process to a halt with another filibuster.

Interestingly, the tone of the poll tax debate changed as the 1940’s arrived. Before this era, legislators made no effort to hide the fact that the poll tax was a deliberate effort to restrict the black vote. As the 1940’s progressed into the 1950’s, the intent had been translated to convey the idea that the concern was based upon constitutional issues, although non-public documents indicate that the underlying purpose of limiting the black vote had not changed.

Interestingly, southern states that had taken the initiative to abolish poll taxes remained in opposition to passage of The Poll Tax Bill. These states were experiencing difficulty with their restoration state in the union combined with their remnant of a dream of separatism. They did not relish the idea of the federal government having the power to interfere in the states’ electoral process, and for this reason sided with those states who were opposed to The Poll Tax Bill.

As his term commenced, President Harry S. Truman created the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, to investigate matters concerning equal rights, including the poll tax. As the Cold War commenced in the 1950’s, the Poll Tax Bill faded into the background as fear of communism took center stage, and it was learned that some Marxist Americans were opposed to the poll tax.

The election of President John F. Kennedy resulted in another look at the civil rights issue, including the poll tax. After consideration of the issue, he decided that the best course of action would be a constitutional amendment, since all efforts to pass legislation resulted in filibuster.

President Kennedy was able to gain the support of senators who had formerly opposed any type of civil rights legislation, and this fact served to bolster support by others who would have most likely opposed its passage.

Although ratification was not accomplished with 100% approval, the Twenty-Fourth Amendment was ratified on January 23, 1964. Thirty-eight states initially ratified the amendment, with four states later ratifying as well. The amendment was rejected outright by the State of Mississippi, and at the time of this writing, eight other states have not ratified the amendment.

In Summary

The Twenty-Fourth Amendment’s journey into being began with the post-Civil War era and reached its zenith in 1964 under the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson. President Johnson referred to the passage of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment as “a triumph of liberty over restriction.” It is an excellent example of the tenacity of the American spirit.