| United States Constitution | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The U.S. Constitution | |

| Preamble | |

| Articles of the Constitution | |

| I ‣ II ‣ III ‣ IV ‣ V ‣ VI ‣ VII | |

| Amendments to the Constitution | |

| Bill of Rights | |

| I ‣ II ‣ III ‣ IV ‣ V ‣ VI ‣ VII ‣ VIII ‣ IX ‣ X | |

| Additional Amendments | |

| XI ‣ XII ‣ XIII ‣ XIV ‣ XV ‣ XVI ‣ XVII ‣ XVIII ‣ XIX ‣ XX ‣ XXI ‣ XXII ‣ XXIII ‣ XXIV ‣ XXV ‣ XXVI ‣ XXVII | |

| View the Full Text | |

| Original Constitution | |

| Bill of Rights | |

| Additional Amendments |

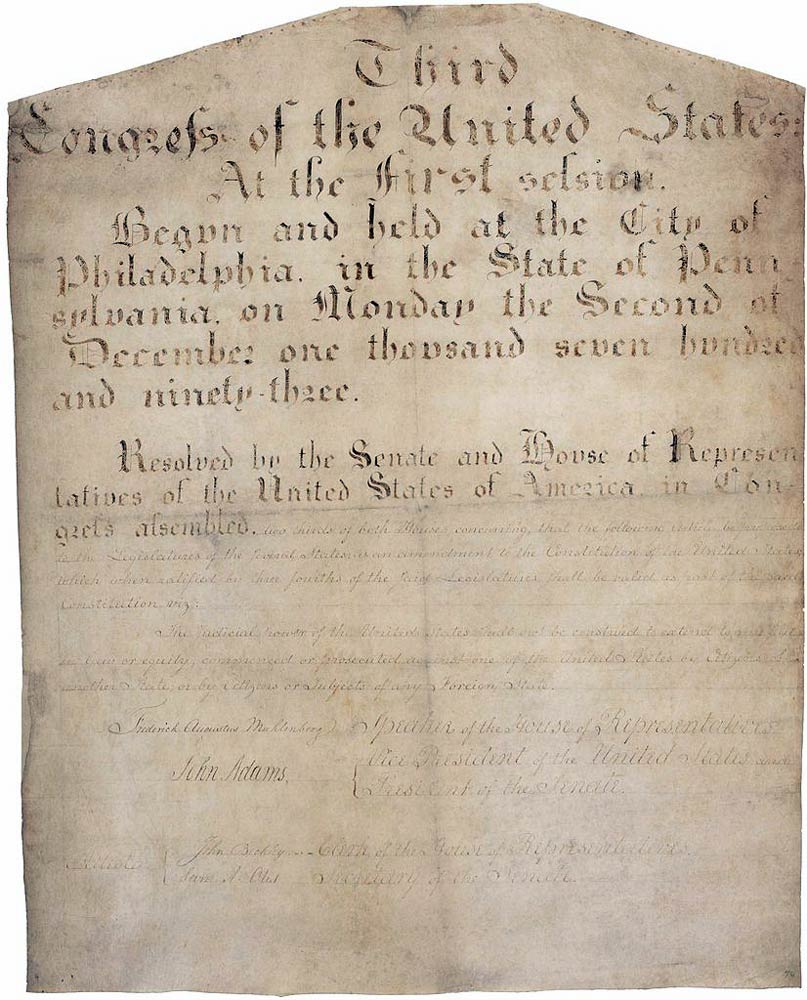

The first amendment to be adopted after passage of the Bill of Rights, the 11th Amendment was approved by Congress on March 4, 1794 and was ratified on February 7, 1795.

This amendment clarified the question of states’ sovereign immunity from suits brought by citizens of other states, or of other countries, and provides that all states shall enjoy sovereign immunity from such lawsuits.

Text

The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.

Basis

The catalyst that sparked the realization that this amendment was needed was generated in Chisholm v. Georgia (1793). In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that superior courts were empowered to consider cases brought by the private citizenry in opposition to states; further, the Court ruled that these states were not protected by sovereign immunity from legal action taken by persons whose citizenship lay with other states, or other countries. The Eleventh Amendment served to clarify Article III, Section 2 of the original Constitution from which the decision in this case was based.

The Question of Immunity

In Chisholm v. Georgia, Alexander Chisholm, a resident of South Carolina, filed a lawsuit against Georgia for breach of contract for supplies that it purchased from Chisholm during the war, yet for which no payment was remitted to Chisholm.

In Chisholm v. Georgia, Alexander Chisholm, a resident of South Carolina, filed a lawsuit against Georgia for breach of contract for supplies that it purchased from Chisholm during the war, yet for which no payment was remitted to Chisholm.

The state of Georgia balked, claiming that its sovereign immunity did not allow such a lawsuit. Annoyed that the state of Georgia was invoking this claim, which in essence had the effect of cutting the higher court’s authority, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Chisholm.

The resultant outcry from this decision brought about prompt action to enact the Eleventh Amendment. In fact, two days after this decision was handed down, a senator introduced a proposal before Congress that did, in fact, become this amendment.

The language of the Amendment is simple. It states that the judicial power of the United States cannot be interpreted to extend to any other lawsuit begun or carried out against one of the states of the U.S. by citizens of other states, or by citizens and/or subjects of another country.

The overall intent of the Eleventh Amendment was to establish a chain of command, with states being subject to federal law, and thus they could not mistreat citizens. By the same token, the states needed a degree of protection from lawsuits that could be frivolous in nature.

Therefore, four recognized points came into being from the Eleventh Amendment and are accepted as the standard protocol:

• Lawsuits may be brought before federal courts against subdivisions of states, such as cities, counties, and municipalities;

• Any state may consent to having a lawsuit against it brought before a federal court;

• Congress has the ability to “abrogate” or remove any state’s immunity from lawsuits in federal court upon satisfactorily showing that its intent in doing so is “unmistakably clear.”

• If federal law is violated by a state, the federal court can specifically name state officials and direct them to comply with the law (although the state cannot be sued in federal court).

It is interesting to note that the language in the Amendment does not address the matter of a state having a lawsuit filed against it by its own citizens. Yet, in 1890, in Hans v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court interpreted the Amendment as indicative of a broad range of sovereign immunity, but not without dissension from opposing justices who wrote in their dissenting opinion that the states, in effect, yielded any rights to sovereign immunity when they ratified the Constitution.

The degree of sovereign immunity granted to states was not all-encompassing. The Supreme Court mandated that states must comply with federal law, and ruled that the federal government may take action to prevent federal officials from violations of federal law.

In Summary

The Eleventh Amendment gave the states sovereign immunity from lawsuits filed by citizens of other states or nationalities. The Supreme Court expounded upon the text of the Amendment by defining the instances in which sovereign immunity is, or is not, applicable. It stands to reason that since states are not truly sovereign (but are answerable to federal law) they are thus under the jurisdiction and protection of the federal government. While states do enjoy some sovereignty, it cannot supersede the authority of Congress and/or higher courts of the land.

An interesting postscript to the story is that, in the case that started it all, Chisholm v. Georgia, the passage of the Eleventh Amendment resulted in the Supreme Court decision (brought forth in Hollingsworth v. Virginia in 1798) that every pending action of Chisholm v. Georgia be dismissed.