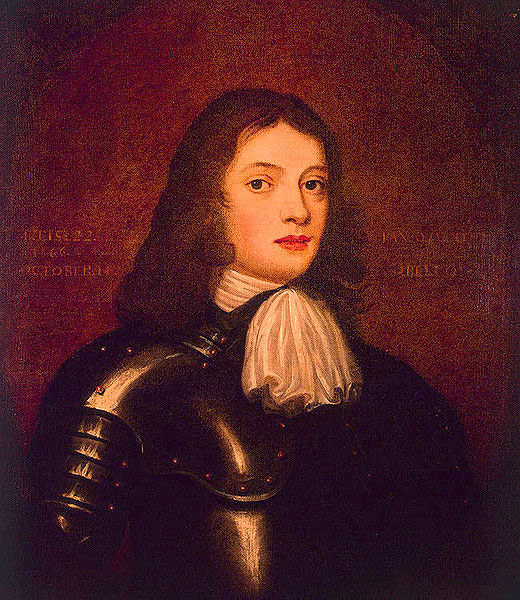

William Penn was born in England in 1644. He was the founder of the province of Pennsylvania, which was at first a British colony, but later became the great state we all know as Pennsylvania – which means in Latin, “Penn’s forest.” While there were many contributors to what would become the U.S. Constitution, his ideas about democracy provided a foundation for the document and for the direction of the new nation.

William Penn was born in England in 1644. He was the founder of the province of Pennsylvania, which was at first a British colony, but later became the great state we all know as Pennsylvania – which means in Latin, “Penn’s forest.” While there were many contributors to what would become the U.S. Constitution, his ideas about democracy provided a foundation for the document and for the direction of the new nation.

Early Life

Penn was raised by Anglican parents in England. When he was 22 he became a member of the Religious Society of Friends, otherwise known as Quakers. They believed in obedience to the inner light, which was a direct manifestation of God, and they did not recognize the authority of any other man or organization, even going so far as refusing to participate in any militia or army service. Admiral Sir William Penn, the younger Penn’s father, was very distressed by the religious beliefs of his son, and it came to be a defining theme in the younger Penn’s life

His Quaker Faith

George Fox, the founding father of the Quakers, was a compatriot of Penn, and they were fast friends. The pair traveled and ministered to other Quakers throughout England and Europe, and Penn authored a defense of the beliefs of the Quakers and vouched for the character of Fox in the introduction to Foxes’ autobiography. Quakers were viewed with suspicion by the contemporary government since they did not follow the religion imposed by the monarchy, nor did they believe in swearing any kind of earthly oath of allegiance or loyalty.

George Fox, the founding father of the Quakers, was a compatriot of Penn, and they were fast friends. The pair traveled and ministered to other Quakers throughout England and Europe, and Penn authored a defense of the beliefs of the Quakers and vouched for the character of Fox in the introduction to Foxes’ autobiography. Quakers were viewed with suspicion by the contemporary government since they did not follow the religion imposed by the monarchy, nor did they believe in swearing any kind of earthly oath of allegiance or loyalty.

Penn’s religious experiences began early when he was a student at Chigwell School in Essex. He was strongly affected by these experiences and his beliefs were strong – strong enough to have the result of getting him exiled from proper English society. His expulsion from the Anglican church and subsequent multiple arrests attested to his allegiance only to God and the principles of Quakerism. One of these arrests led to a trial by jury which was then overturned by a judge – resulting in a new law that prohibited any English jury from being under the control of a judge – an important step forward in English jurisprudence. Unfortunately, the government of England pursued a policy of persecuting the Quakers, to the point that Penn and others made the decision to go to the new world and establish a new free colony of Quakers there.

Settling in the Colonies

Before Penn had even arrived in the colonies, he and a number of influential Quakers were granted a province in the colonies called West New Jersey in 1677. English settlers from various places in the British Isles arrived in the colonies and the town of Burlington was founded by them. While Penn was still in England, he wrote a charter for the new province that established guarantees of jury trials, religious freedom, protection from illegal and unjust imprisonment, and free elections.

Ironically, because the King owed a loan to Penn’s father, he granted a substantial area of land in the colonies to Penn, at which time it received the official name of Pennsylvania. Possibly, the land grant was influenced by the wish of the king to establish a place distant from the crown for religious outsiders to be free to follow their own beliefs and callings. A pioneering county in Pennsylvania was known as Buck’s county, named after its namesake in England from which a large proportion of colonizers had come, as well as being the family seat of the Penn clan.

Penn’s new colony was the site of a grand experiment in democracy and religious freedom. While he and the colony were nominally subject to England’s King Charles, he implemented a plan that provided a system of democratic rule including religious freedom, trial by jury of peers, a representative form of government, and a policy of separating powers. All of these basic principles were to become foundation ideas for the new government of the United States and its constitution.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania was a forward-looking place to live and a frontier as well. It drew settlers who wanted to be free to worship God as they saw fit. Many groups came to Pennsylvania, including the Amish, Lutherans, Mennonites, French Protestants, and anyone who believed in God, as well as Quakers from a variety of locations. In addition to religious freedom, the province was Penn’s venture into capitalism, as he believed that it would be an enterprise that made a profit for him and his growing family. An early entrepreneur, he advertised the advantages of the settlement in many potential markets in the old world, and in the process drew settlers from many different backgrounds and languages. While his efforts were sincere and commendable, he was never able to make a profit from the venture, and he was much later thrown into debtor’s prison in his homeland – when he died in 1718 he was a pauper, without a penny to his name.

Pennsylvania was a forward-looking place to live and a frontier as well. It drew settlers who wanted to be free to worship God as they saw fit. Many groups came to Pennsylvania, including the Amish, Lutherans, Mennonites, French Protestants, and anyone who believed in God, as well as Quakers from a variety of locations. In addition to religious freedom, the province was Penn’s venture into capitalism, as he believed that it would be an enterprise that made a profit for him and his growing family. An early entrepreneur, he advertised the advantages of the settlement in many potential markets in the old world, and in the process drew settlers from many different backgrounds and languages. While his efforts were sincere and commendable, he was never able to make a profit from the venture, and he was much later thrown into debtor’s prison in his homeland – when he died in 1718 he was a pauper, without a penny to his name.

For two years Penn was able to actually live in his namesake province, from 1682 to 1684. He was successful in drawing up the plans for a model city named Philadelphia – the city of brotherly love – and thereafter followed through on exploring the land bearing his name. He established a close and working relationship with the Native American Delaware tribe, and made sure that they had been justly and completely compensated for lands they had given over to the colony. Obviously sincere in his feelings and dealings with the indigenous Americans, he learned dialects of many different Indian tribes so he could enter into negotiations without the need of an interpreter. He initiated legal statutes that gave the Native Americans rights to a fair trial with Europeans, and succeeded in enacting these measures, even though subsequent colonists did not follow his injunctions and precedents. As a result of his successful communications and treatment of the natives, Pennsylvania was spared much of the trouble meted out to other colonies in the coming years.

His efforts to deal fairly with the natives continued in later years, most famously when he negotiated a treaty and actually paid a fair market amount for lands acquired. While the veracity of this treaty was later questioned, it has stood the test of time and history and remains a shining example of the way the indigenous Americans should have been treated.

Penn’s Later Life

Penn had to return to England for pressing family and business matters, but was able to come back for a final visit in 1699. During that sojourn he proposed a federation of the English-ruled colonies. He had desired to live in his planned city of brotherly love, Philadelphia, but had to make his way back to his land of birth for financial reasons in 1701. During the next ten years of his life he found himself embroiled in legal battles with a former financial consultant and adviser, named Philip Ford. While still involved in legal proceedings in England, he suffered a stroke that left him unable to speak or care for himself. He passed away at his English ancestral home in 1718, and was interred adjacent to his wife in a Quaker cemetery. The entire colony of Pennsylvania was still owned by his descendants up to the final days of the American Revolution.