| Vo Nguyen Giap | |

|---|---|

| Viet Cong Commander | |

| Years of Service | 1944-1991 |

| Born | Aug. 25, 1911 Quảng Bình Province, French Indochina |

| Nationality | Vietnamese |

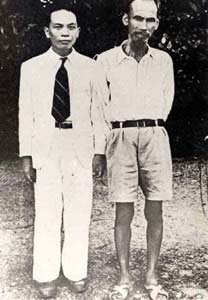

Vo Nguyen Giap (born August 25, 1911) was one of the most well-known of the Viet Cong’s military commanders during the Vietnam War. He was also a high-ranking officer in the war in Indochina in the late 1940s. Aside from his army roles, Giap spent time as a journalist and a government minister. At his peak, his prominence as a general was second only to Ho Chi Minh himself. In later life, Giap became known as a writer on military strategy.

Early Life

Giap’s childhood gave little hint of his future direction because his family was sufficiently wealthy and they could give him a fairly comfortable life. However, at the age of 14, shortly after becoming employed as a power company’s messenger boy, Giap became a member of the revolutionary group Tan Viet Cach Mang Dan. Some authorities claim that he was expelled from a prestigious school for organizing student strikes, although this is disputed by others.

At the University of Hanoi, Giap became a doctor of economics before leaving to teach history. In 1931, he joined the Communist Party, becoming involved in demonstrations protesting French rule in Vietnam. These actions led to his arrest the following year, after which he served a year and a half in jail. Vietnamese communism was banned by the French in 1939, and Giap was forced to flee to China, where he first met Ho Chi Minh.

During his time in China, Giap’s sister – who was also a strong opponent of French colonialism – was also arrested, as was his wife. Both women died in prison. His sister died by means of execution and his wife of natural causes. These two major bereavements had a galvanizing effect on Giap and he felt their loss keenly. As a response to what happened, he resolved to direct all his efforts towards forcing France to pull out of Vietnam.

World War II and After

After Japan invaded China during World War II, Giap was involved in the organized resistance against the Japanese. These years also gave him the opportunity to hone his abilities as a guerrilla fighter, perfecting tactics later used with great effect by Mao Zedong. In August 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies and Vietnam was left without an effective ruler. France had been removed by the Japanese and a provisional government—the Democratic Republic of Vietnam—was announced by Ho Chi Minh. Giap was appointed Minister of the Interior of the new government.

After Japan invaded China during World War II, Giap was involved in the organized resistance against the Japanese. These years also gave him the opportunity to hone his abilities as a guerrilla fighter, perfecting tactics later used with great effect by Mao Zedong. In August 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies and Vietnam was left without an effective ruler. France had been removed by the Japanese and a provisional government—the Democratic Republic of Vietnam—was announced by Ho Chi Minh. Giap was appointed Minister of the Interior of the new government.

However, the Allied Powers had already formulated a plan for Vietnam that was very different to that which Minh had devised. Under this arrangement, Nationalist China would take control of the northern half of Vietnam with the southern portion of the country being controlled by the United Kingdom. France, which had made no secret of its wish to reassert its own authority in the region, was frozen out. However, a year after the end of the war, France did manage to re-establish control when British and Chinese troops pulled out.

Conflict Breaks Out Again

France would not recognize the government of Ho Chi Minh. This rapidly led to conflict with Giap’s forces. At first, the better-equipped French soldiers were substantially superior to the Vietnamese, but their thinly-spread nature eventually allowed Giap time to strengthen his own forces. After 1949, when Mao’s communists had fully taken control of mainland China, they were able to give support to Giap’s men and provide a very useful base where they could recover from their injuries away from the front lines. Giap was further helped by a number of communist guerrillas from China.

Before long, Giap had become known as a commander who was highly proficient at guerrilla warfare. Against the French troops, however, he also employed more conventional methods to great effect. Navarre, in command of the French at Dien Bien Phu, intended to entice Giap’s men out into the open in order to set up a conventional mass battle. Instead, he was outmaneuvered by Giap, who effectively surrounded the Frenchmen as well as outnumbering them by five to one.

Mao’s China had also provided Giap with anti-aircraft guns and highly-damaging 105mm artillery pieces. These were deployed to prevent the French from supplying their soldiers via airdrops. Waiting until he felt that his opponents had been weakened sufficiently, Giap then launched a frontal attack. This began on March 13, 1964. Less than two months later, he received the French army’s surrender; 18,000 of their men had been killed, wounded, or captured. On May 8, France announced that it was ready to withdraw completely from Vietnam. This crushing victory brought Giap high renown as a general.

Mao’s China had also provided Giap with anti-aircraft guns and highly-damaging 105mm artillery pieces. These were deployed to prevent the French from supplying their soldiers via airdrops. Waiting until he felt that his opponents had been weakened sufficiently, Giap then launched a frontal attack. This began on March 13, 1964. Less than two months later, he received the French army’s surrender; 18,000 of their men had been killed, wounded, or captured. On May 8, France announced that it was ready to withdraw completely from Vietnam. This crushing victory brought Giap high renown as a general.

Vietnam War

Giap was commander-in-chief of the forces of North Vietnam throughout hostilities with the United States. The Viet Cong’s guerrilla tactics proved to be extremely effective with Giap also launching a hearts-and-minds campaign by getting his troops to befriend and work for Southern villagers. Even so, some of the southerners were hostile to Giap’s men and most authorities believe that his forces then dealt out brutal retribution. Giap, in other words, was far from being universally hailed in South Vietnam as a liberator freeing them from American tyranny.

Giap’s actions were not confined to guerrilla warfare. He employed a more conventional approach in the 1968 Tet Offensive. U.S. President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization” initiative, however, reduced the number of American servicemen serving in Vietnam, thereby allowing the North Vietnamese a better chance of success against the southerners. On April 30, 1975, the Viet Cong entered Saigon and a socialist republic was proclaimed. Giap was given the dual roles of Minister of Defense and Deputy Premier. However, by 1982, he had been stripped of both posts, and he went into retirement.

Some historians see Giap as one of the modern era’s most significant and substantial military leaders, mentioning him in the same breath as the likes of General Douglas MacArthur and the Duke of Wellington. Others, however, take the view that Giap’s successes came only at immense human cost and that the North Vietnamese troops suffered excessive casualties because of his disregard for the safety of his men.