| Second Battle of Bull Run | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Military Leaders | |||||||

| John Pope | Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| 62,000 | 50,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and Deaths | |||||||

| ~10,000 killed and wounded | ~1,300 killed ~7,000 wounded |

||||||

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

The Second Battle of Bull Run was fought between August 28 and 30 in 1862, and was the second time Union and Confederate forces had met at Bull Run, near Manassas in Prince William County, Virginia. The first battle had taken place in July of the previous year and resulted in a defeat for the Federal army.

The second battle pitted the Federal troops in the Army of Virginia, commanded by Major General John Pope, against the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee.

Background

The President, Abraham Lincoln, had placed Major General Pope in charge of the Army of Virginia, a newly established force. Lincoln was concerned by the failure of the Army of the Potomac’s Peninsula Campaign under Major General George B. McClellan, and wanted a commander who had a more aggressive approach.

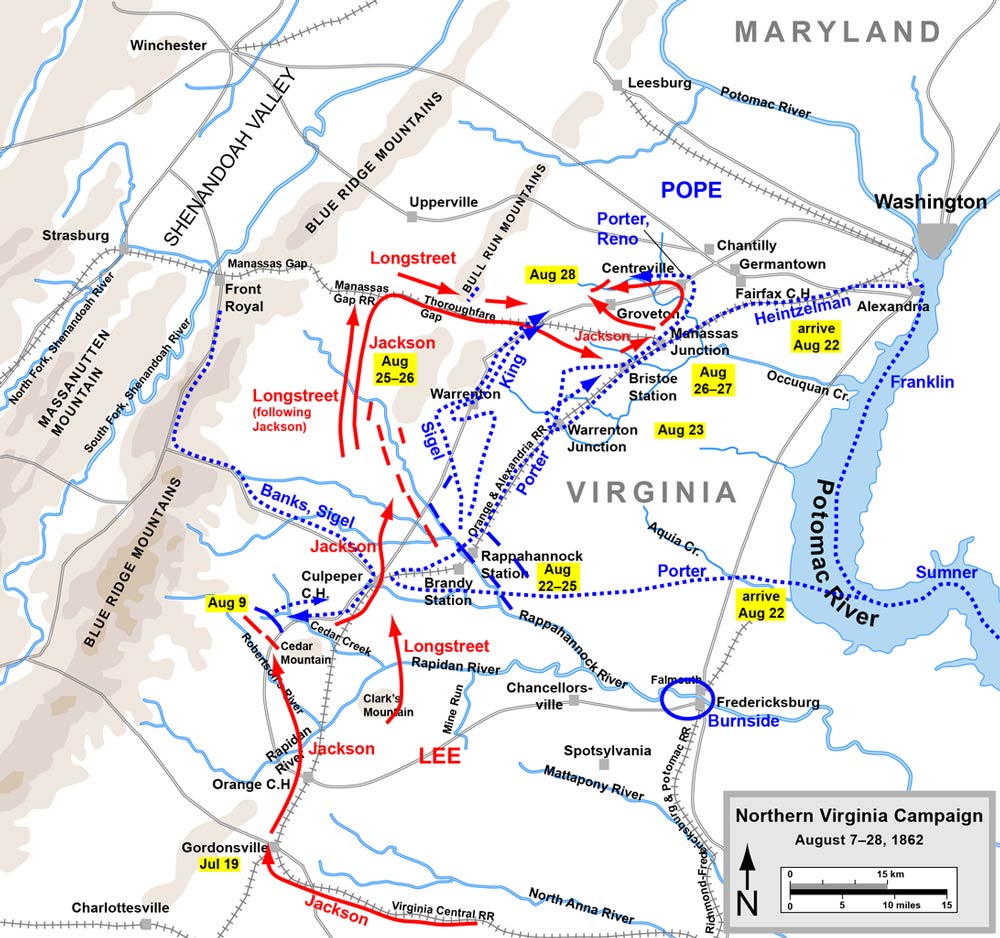

Pope’s instructions were to defend Washington and the Shenandoah Valley against the possibility of a Confederate attacks. He was also to move his troops towards Gordonsville in an attempt to take Confederate attention away from McClellan’s army, then located in the Virginia Peninsula.

Following several successful engagements against McClellan’s troops, General Lee was confident enough to take some of his army from defensive duties around the Confederate capital at Richmond. He sent Stonewall Jackson to Gordonsville to halt Pope’s advance, and later sent an additional 12,000 men under the command of Major General A.P. Hill to support Jackson.

Pope’s and McClellan’s armies were widely separated, and Lee decided to try to destroy Pope’s army, and then take on McClellan’s, which Lee thought was the weaker of the two.

General-in-Chief of the Union army, Henry W. Halleck, sent orders to McClellan on August 3, instructing him to join up with Pope’s men on the approach to Gordonsville. McClellan’s military career is full of episodes of hesitancy, and once again he delayed and did not begin moving until August 14, eleven days after receiving his orders.

Between August 22 and 25, Pope’s and Lee’s forces engaged in a number of minor encounters along the Rappahannock River. During this period, McClellan’s men had begun to arrive and reinforce Pope’s forces.

Recognizing that he was being outnumbered, Lee decided to try to cut off Pope’s supply lines by taking the Orange and Alexandria railroad. He dispatched half his forces on a flanking maneuver, and on August 26, Stonewall Jackson took control of the railroad at Briscoe Station, followed by Manassas Junction and the major Federal supply depot there. He then moved to take up a defensive position at Stony Ridge.

Pope was forced to retreat from the Rappahannock, and Lee’s army took up defensive positions around Bull Run.

The Battle

The battle began on August 28. The Confederates had set up positions to prevent the Union army from moving along the Warrenton Turnpike. Units of the Union army moved to the turnpike in an attempt to consolidate forces with Pope, whose main force was now located at Centerville, and these were attacked by Jackson’s units.

Meanwhile, Confederate forces under the command of Major General James Longstreet defeated the Federal forces at the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap. This victory enabled Longstreet’s men to move to join up with Jackson’s.

On August 29, Pope launched an offensive against Jackson’s troops, who were now in defensive positions along an incomplete railway grade. Pope believed that some of his forces were in a position to prevent Jackson from retreating to the Bull Run Mountains. Jackson was confident that his defensive position was solid and he could hold out until Longstreet’s troops arrived. The Confederates successfully held off the Federal offensive, and later in the day, Longstreeet’s men arrived from Thoroughfare Gap.

In the early morning of August 30, the final section of Longstreet’s units arrived and took up position in darkness at Groveton. As the sun rose, these units realized they were completely isolated and were far too close to the Union forces. Their commander, Richard H. Anderson immediately ordered a retreat.

Pope’s Mistake

Pope was convinced that the entire Confederate army was now in retreat, and planned to pursue them. Despite intelligence that the Confederates were still in position, Pope sent his soldiers forward to renew attacks on the Confederates. He ignored the advice of several of his staff to proceed with care.

Pope ordered Major General Fitz John Porter’s to attack along the turnpike. At the same time, other units were to move forward along the Union right flank. Pope ordered these troop movements constantly, believing he would be pursuing retreating Confederate forces.

The Confederates, rather than retreating, had moved heavy artillery to high ground overlooking Brawner Farm in anticipation of a Union attack. Secondly, Porter’s men were not in the best position to follow Pope’s orders, and there was a significant delay before they were ready to carry out the instruction. The Federal troops were repelled by a heavy Confederate artillery bombardment and the attack failed.

Counterattack

Longstreet then launched a counter attack, using 25,000 men in the assault. The objective was to take Henry House Hill, as this location had proved decisive in the First Battle of Bull Run. Throughout the day, fierce fighting took place as ground was won and lost.

Pope also recognized the strategic importance of Henry House Hill and initiated a withdrawal to reinforce his defenders there. These troops came under intense pressure from Confederate troops, who succeeded in defeating several units of artillery and infantry.

As darkness fell, Pope had managed to withdraw to Henry House Hill and establish a solid defensive line. So intense had the action been that the Confederate forces were short on ammunition and exhausted from the action. This gave Pope the opportunity to begin an orderly withdrawal to Centerville under cover of darkness.

Just as in the First Battle of Bull Run, the Union army had been forced into retreat. However, this time the retreat was orderly and disciplined, and the army did not suffer the devastating humiliation and losses it had sustained in the retreat in July of the previous year.

After the Battle

The Second Battle of Bull Run led to heavy casualties on both sides. The Union army lost around 10,000 men in total, while the Confederates lost about 8,300. On September 12, Pope was relieved of his command.