The Chinese Qing Dynasty was a monarchical regime led by the Manchus that ruled from 1644 to 1912. The majority of the population abided by local or folk religion, shamanism, and animism focused on familial values and veneration for local spirits and ancestors. Family traditions such as mourning and burial rites were widely observed, a display of the deep devotion of the Qing to filial piety. Additionally, shamanic shrines and shamans were used for spiritual ceremonies. The imperial family also participated in shamanistic rituals performed during the Chinese New Year.

The primary belief system at the time was Confucianism, although whether it was considered a religion or a philosophy has been widely debated. The two other major religions in the country were Buddhism and Daoism, otherwise known as Taoism. All three of the major religions could be practiced alongside folk religion. Meanwhile, the imperial Manchus covertly continued their Tibetan Buddhism customs. Islam and Christianity were also slowly growing in their following during the Qing dynasty.

Confucianism

Confucian teachings were derived from the philosopher Confucius who authored several works that highlighted moral values, the most famous being the Lunyu. The philosopher emphasized developing a strong character and following ethical guidelines, contributing to “cosmic harmony .” Furthermore, one of the foundations of Confucianism is the idea that one must “Do not do unto others what you would not want others to do unto you.” Deviating from these principles was the cause of any discord or calamities.

During the transition from the Ming to the Qing Dynasty, conflicts arose among Confucian followers due to the contradiction of obedience to the new administration and the virtue of loyalty to the past leaders, prompting the diversification of the populace’s perspectives.

The well-known Confucians during the Ming and Qing Dynasties were Wang Yangming, and Huang Zongxi were symbols of this shift in Han Chinese mentality. The former urged believers to think independently and to express their individuality instead of simply following the authorities without good reason. The latter was critical of imperial rule and its autocratic ways.

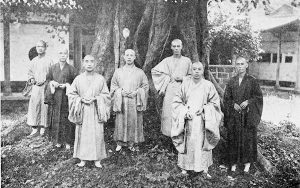

Buddhism

All the Manchu emperors from the Qing Dynasty overtly practiced Confucianism, allowing it to be China’s dominant and official religion. The imperial palace had dedicated altars for sacrifices and upheld Confucian policies intending to gain support among the Chinese populace. This was because the Manchus were not the Han Chinese that was ethnic to China, but they were nomadic people that came from a line of Jurchen rulers in the northern part of China during the 12th century. They were related to the Mongols and the Turks, albeit distantly.

The religion and the installment of Chinese officials in the palace garnered the Manchus favor among their constituents as part of their Mongolian protocol to relate to their conquered peoples’ culture. Clandestinely the Manchus kept their Tibetan Buddhism tradition that had been acknowledged during the previous Ming Dynasty. This connected them to the most common religion of the Tibetans and the Mongols.

The Manchus’ worship of Tibetan Buddhism resulted in the Dalai Lama’s visit to China in the year 1652. The Dalai Lama is the most highly regarded religious leader of the Tibetans. During the Qing Dynasty, the Dalai Lama and his successors were given the status of Qing protectorate as Tibet was considered one of their vassal states that they must safeguard.

During the Battle of Nanjing in 1853, numerous monks were killed in the capital of Nanjing. The Taiping leaders then enforced a policy that required monks to own licenses. The Buddhists in China developed their own specific belief system following Tibetan Buddhism. This stronger identity enticed people from other Asian countries to study and learn about Chinese Buddhism. Consequently, the Sri Lankan Buddhist missionary Anargarika Dharmapala traveled to Shanghai to explore China in 1893. He aimed to inspire the Chinese Buddhists to head to India and cultivate Buddhism there. However, Anargarika chose to stay in China, joined by Japanese Buddhist missionaries who actively inculcated Buddhist beliefs in others at the start of the 19th century.

Taoism

Taoism, also referred to as Daoism, was a philosophy and religion that stemmed from the teachings of the philosopher Lao Tzu. He was the writer of the Tao Te Ching, or The Way and Its Power, the book from which believers learn how to live a balanced life in harmony with the universe or Tao. The writings are composed of sayings from the 3rd to 4th century that advise on how to live virtuously that can result in immortality.

An important aspect of Taoism is worshiping the local gods and other immortals. This linked the religion to the shamanistic customs of the Chinese. The Ming dynasty rulers had previously used this connection to appeal to their populace; thus, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty followed their strategy.

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam

The three monotheistic religions that attempted to instill their own beliefs in the Chinese were Christianity, Judaism, and Islam— all sent missionaries to indoctrinate the Chinese.

In the middle of the 1800s, Islam reached the cities with Islamic Turkestan immigrants, increasing the converts in the area. Meanwhile, Christianity had already had a foothold in the country for centuries due to visiting Jesuit priests that had stayed in the Chinese court.

Islam was almost insignificant in China until around the mid-1800s, when its influence spread from Islamic Turkestan and from Chinese cities, which had a substantial proportion of Muslim immigrants or converts. It played almost no role in official society right up to the end of the Qing period in 1911.

Conversely, hundreds of Catholic missionaries had already arrived in the country during the previous administration, the Ming dynasty. The priest Adam Schall von Bell was the first missionary from the West to bring the calendar used in their motherland.

The Catholic missionaries allowed the Chinese to continue with their shamanic practices while they impressed the imperial family with their knowledge of astronomy and cartography. However, they fell silent when they were not accepted by the imperial family for some time until 1692 when the Kangxi Emperor issued an edict of toleration. Franciscan and Dominican religious leaders resumed their evangelization in rural communities with the same policy that adopted the locals’ already established shamanistic beliefs.

In the 18th century, Protestant missions, alongside Islamic and Judaist missions, came to China. Some historians believe that there may have been as many as 100,000 Christians in China in 1700.

The Yongzheng Emperor that rose to the throne in 1724 called Christianity a “heterodox religion,” branding it as a cult-like belief system and discouraging the Chinese public from opening up to Christian missionaries. However, the Christian clerics did not establish Chinese leadership for their respective sects of Christianity and were allowed to remain in China. Their number of conversions would continue to grow.

In 1811, the Jiaqing Emperor illegalized Christianity, but a Treaty lifted this in 1846. Christian missionaries once again continued to convert the Chinese. In the 1900s, there were around 1,400 Catholic religious members from other countries in China and almost 1 million converts.

In contrast, the Chinese Jewish community that had first been established in the 8th century was slowly decreasing. By the middle of the 19th century, there were no more Jews that were capable of reading Hebrew in the province of Kaifeng. Later, in the 1980s, the Jewish Chinese rebuilt their following, and by the 1990s, Judaic studies could be taken in universities.