The Qing dynasty was reigned from 1636 to 1912, ruled by the Manchus who came from a Northeastern portion of China called Manchuria. While they were in power, they adopted many cultural practices that were already established by the Han Chinese, the dominant ethnicity in China at the time. The Manchu leaders also cultivated a relationship with the Mongols, who also inspired their way of living.

The Qing dynasty continued Ming dynasty structures such as the civil service examination and the primarily Confucian traditions. At the same time, the Manchus observed Tibetan Buddhist religious practices and spoke both Manchu and Chinese languages in court.

The abundance experienced during the Qing period is attributed to three emperors that impacted culture at that time, namely: Kangxi emperor, Yongzheng emperor, and Qianlong emperor.

Kangxi emperor (1661 to 1722) brought about prosperity during his rule; he was responsible for creating the Kangxi dictionary, which promoted the multilingual profile of his constituents. Secondly, Yongzheng emperor (1722 to 1735)was a strict administrator that enriched the country and allowed the arts to flourish. Lastly, Qianlong emperor was dubbed as a “patron of the arts,” owning an expansive collection of artwork.

Literature and the Arts

During the Qing dynasty, the fastest developments in culture were in poetry and painting. One of the key achievements was the composition of a rhyming dictionary in 1711. This document was printed, published, and is still used at present. Consequently, literature was popularly consumed by the male gentry class, although these pieces were often composed by women.

In 1782, the widest compilation of poetry and prose was gathered and completed at the command of the Qianlong emperor. It was called the Siku Quanshu and was even more extensive than the one Yongle emperor had made during the Ming dynasty. 10,680 titles can be found on its pages, with 3,593 summaries alongside it.

The Gujin Tushu Jicheng, or the “Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times,” was also made during the Qing dynasty, requested by Kangxi. Also known as the Imperial Encyclopedia, it was a collection of all the literature from decades before that and held illustrations and written works about various topics from religion, social customs, and the like. It was completed during his son Yongzheng’s reign, but he credited its creation to his father. The book had around 160 million words.

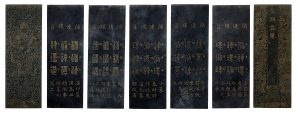

Another compilation commissioned by Kangxi was the Kangxi Dictionary, the most reliable written document on Chinese characters. This was to standardize the Chinese writing system and honor Confucian ideals. The emperor commented that many interpretations could be made of old texts due to each individual’s different meanings regarding each Chinese character. The dictionary was widely used to prevent these misinterpretations and holds 47,035 characters.

Aside from the imperial collections, the Six Records of a Floating Life, was one of the important literary works of the time. It was an autobiography written by Shen Fu, a bestseller that documented mundane life with topics such as the beauty of his wife and childhood memories.

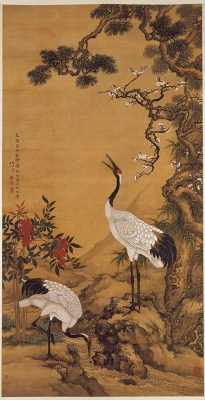

In terms of arts, two of the “Four Arts” were calligraphy and painting. Imperial scholars and painters were often employed by aristocrats, officials, or by the emperor himself to create pieces. The individualist art style also emerged during the time, conveying themes related to freedom and moral outlooks that sometimes stemmed from the Manchu-led rule. Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors were also known for asking the Italian Jesuit artist Giuseppe Castiglione to paint for them, which destigmatized the patronage of foreign artists.

Scholarly subjects were also more accessible with such personalities as Huang Zongxi being known for his political commentary. The founder of the Zhejiang school was a critic of the Chinese political system and its authoritative nature. Another Ming loyalist that was prolific in his writings was Wang Fuzhi. Much like the two former scholars, Yanwu Confucian writer who opposed the Qing dynasty. The three spread Neo-Confucian ideas and dialogue.

Despite the anti-Manchu stance of many scholars, the emperors remained patrons of the literature and prose brought about by philosophers and scholars.

Tea Drinking Culture

The act of drinking tea which had slowly faded in popularity throughout Chinese culture was revived during the Qing dynasty, with both the imperial court and common people enjoying tea as part of everyday life.

In the palace, lavish tea sets became a staple. The Tea Feasts that were first celebrated during the Tang dynasty were once again practiced with more extravagant detail. In particular, Qianlong emperor held the fanciful annual “Sanqing Tea Feast” at Chonghua Palace, which the emperor bestowed upon his high-ranking officials. Furthermore, the “Qian-sou Banquet” was also held during the Kangxi rule and then the Qianlong rule. The massive feast included 3,000 officials and other aristocrats during Qianlong’s 61st year as emperor. The festivities started and ended with the act of drinking tea. Tea parties at the Forbidden City usually took place in the Wenhua Hall or the Hall of Literary Glory, the Chonghua Palace or the Hall of Double Glory, and the Qianqing Palace or the Hall of Heavenly Purity.

Tea drinking was also done in the Imperial Academy as a way to honor Confucius, and the act was generally connected to the philosophy. Thus, it was often integrated into important ceremonies and occasions. Qianlong paired tea drinking with writing poetry as he compiled the Siku Quanshu. Lastly, another notable practice of the imperial family was drinking milk tea which was often a combination of black tea and milk.

For the common folk, the trend culminated in the rise of modern tea houses all over the country. These tea houses became the standard meeting places for conversation or for solitary reflection. The multicultural attitude of the Qing was exemplified in tea drinking as all Chinese drank tea, not only the Han Chinese.