| Peninsula Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Military Leaders | |||||||

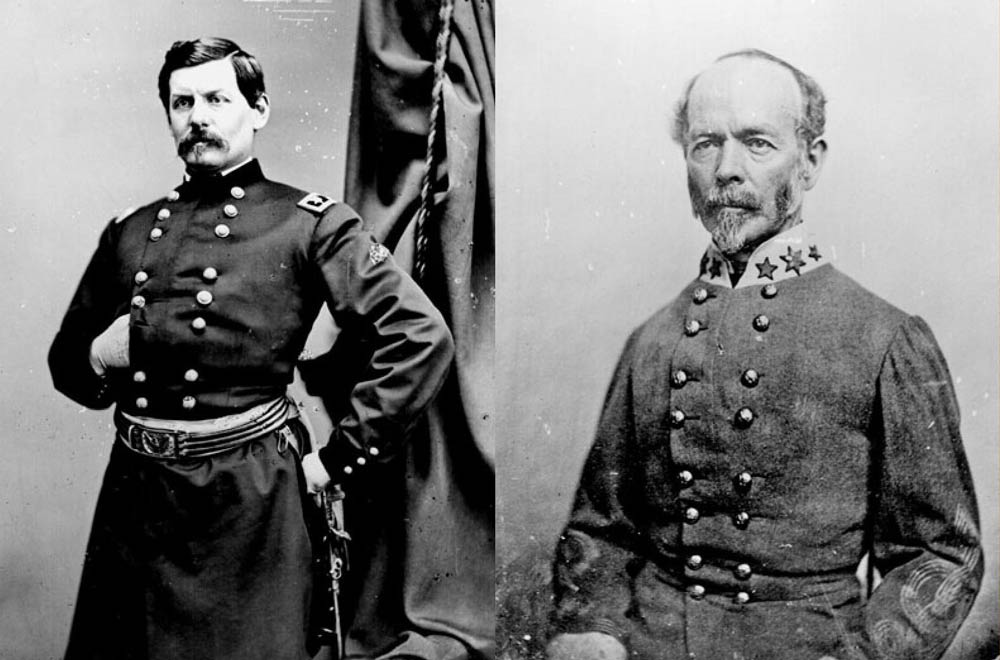

| George B. McClellan | Joseph E. Johnston | ||||||

| Military Units in Battle | |||||||

| Army of the Potomac | Army of Northern Virginia | ||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| approx. 121,500 | approx. 92,000 | ||||||

| Battles Involved | |||||||

| Siege of Yorktown (April 5 – May 4, 1862) Battle of Williamsburg (May 5, 1862) Battle of Eltham’s Landing (May 7, 1862) Battle of Drewry’s Bluff (May 15, 1862) Battle of Hanover Court House (May 27, 1862) Battle of Seven Pines (May 31 – June 1, 1862) Seven Days Battles (June 25 – July 1, 1862) |

|||||||

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

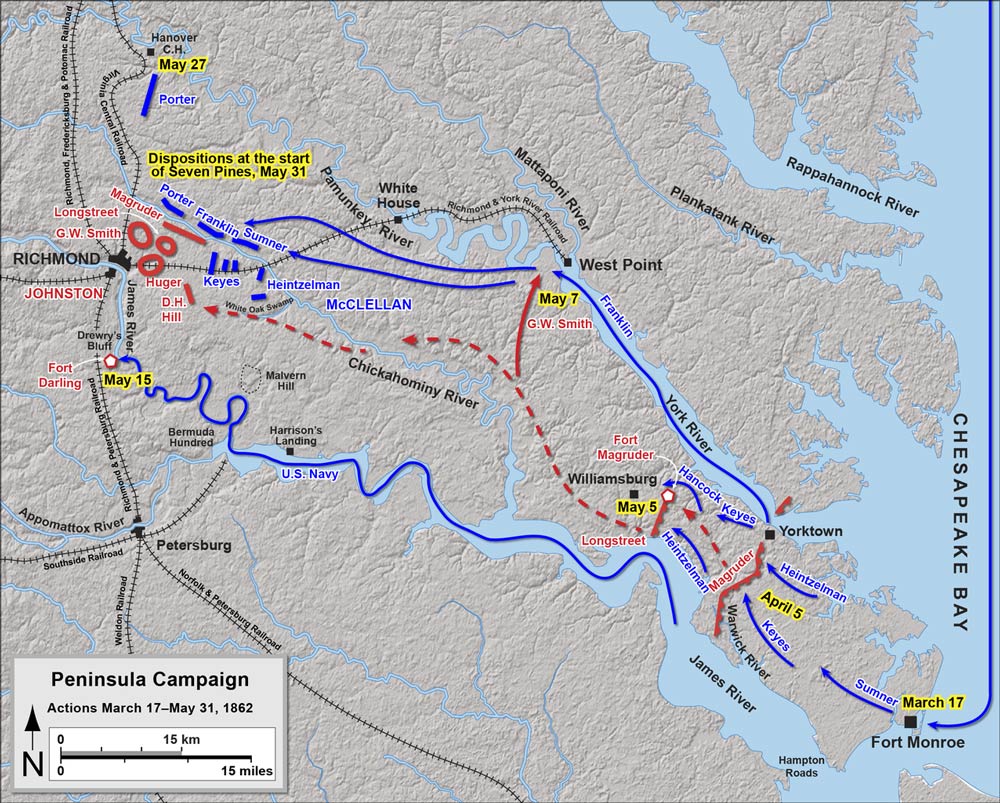

The Peninsula Campaign (often referred to as Peninsular Campaign) was a major Union operation during the Civil War, which commenced in southeastern Virginia. The operation started from March through July 1862, and was the first major offensive in the Eastern Theater. In this campaign, the Union army was led by Major General George McClellan. It was a major turning point against the Confederacy in Northern Virginia and was intended to capture Richmond, the capital of the Confederate. Having moved his Army of the Potomac to Fort Monroe by boat on the Atlantic coast in April, McClellan decided to proceed toward Richmond through the peninsula formed by the James River and York. McClellan was very cautious and refused to launch any attack until late in May.

The first stage of this operation ended in the indecisive Battle of Seven Pines. Here Confederate General J. Johnston was injured and the command was passed to General Robert Lee. The Peninsular Campaign also comprised of one of the major battles in the Civil War: the Seven Days Battles.

General Versus the President

President Lincoln had named McClellan to replace Winfield Scott as the general in chief of all Union troops in November 1861. McClellan was convened to Washington following the overwhelming defeat at Bull Run, the previous July. Since then, McClellan managed to shape most of the inexperienced volunteer troops into effective disciplined forces, referred to as Army of the Potomac. McClellan was a cautious man and always overestimated his enemies. It’s for this reason that the president got frustrated with his unwillingness to take the initiative and issued General War Order No. 1, requiring all troops to move forward.

However, McClellan objected to the president’s idea, convincing the president to further reschedule the offensive attack against Confederate army under the leadership of Joseph Johnston. McClellan preferred to advance his men down the Chesapeake by a boat instead of an overland offensive. This way, he could get between Johnston’s troop and the Confederate capital: Richmond. Early in March 1862, Lincoln agreed to this plan, but demoted McClellan as the Union general in chief to a commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan was also supposed to leave enough troops to safeguard Washington.

Campaign Preparation

Although McClellan got the approval he so much needed for his planned offensive, General Johnston on the other hand removed his men from Manassas to a more easily defendable position, about 40 miles south to a place called Culpeper. The Union Army inspected the vacated Confederate works and disclosed that the rebels’ defense was much weaker than what McClellan claimed. From then on, General McClellan’s persistent demand for more men to face the superior Confederate forces were unattended to in Washington.

Frustrated by Johnston’s move, McClellan then decided to move his Army of the Potomac to Fort Monroe by boat. From there, his army would advance to the peninsula towards Richmond, obliging Johnston to head south to secure the Confederate capital. Once again, McClellan’s plan was halfheartedly accepted by Lincoln and the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. Later on, the president learnt that McClellan had not left troops to defend Washington. Lincoln ordered an entire large corps not to advance toward McClellan. With that order, McClellan advanced to Fort Monroe with 100,000 men instead of the 150,000 he had demanded for.

From Yorktown to Seven Pines

McClellan thought that he would find the main Confederate force at Yorkton on the Peninsula. Despite the Confederates having fortified a line across the Peninsula with just 11,000 troops, McClellan hesitated to go on the offensive once again. By this time, Johnston’s troop was about 80 miles away, but McClellan continued to defy the President’s repeated orders to launch an attack. Finally, McClellan ordered his army to proceed up the peninsula, after learning that Johnston had pulled his troops from Yorktown toward Richmond. By the third week of May, McClellan was approaching Richmond.

Although the Federal side had 100,000 men against 60,000 Confederate defenders, McClellan still wanted more reinforcements. On May 31, the Confederates launched an attack against two Federal corps 6 miles east of Richmond, at the South of the Chickahominy River. The two-day Battle of Seven Pines and Fair Oaks saw the rebel defenders drive one Union corps back. They also inflicted heavy casualties on the Federal side before McClellan stabilized his line. On their side, the Confederate suffered a major blow when General Johnston was critically injured. Confederate president Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with General Lee, a move that would have weighty effects for the rest of the clash.

Seven Day’s Battle

Throughout June, Lee planned a counteroffensive, while McClellan continued to demand for more troops and supplies from Washington. To him, he was facing about 200,000 enemy troops, while in reality Lee’s maximum force comprised of 92,000 men. On July 26, Lee left some divisions to defend Richmond and attacked McClellan from the right side north of the Chickahominy. In the Seven Day’s battle, General Lee ordered a series of attacks at Gaines’ Mill, Frayser’s Farm, Mechanicsville, and Malvern Hill. McClellan won most of the skirmishes during the seven days, but ordered his army except the Fifth Corps to retreat to Harrison’s Landing on the James. These news caused northern morale to fall.

Campaign Aftermath

After redeploying his troops toward south of the river, McClellan continued to plan to siege and capture Richmond, but he lost the calculated initiative and did not regain it ever again. General Lee on the other hand, took the advantage of the month-long silence in McClellan’s advance, to strengthen his defense in Richmond and advance them south to the James River. Here, he built 30-mile long defensive lines. The second phase of this operation saw Lee Launch fierce counterattacks on the Union camp at the east of Richmond during the Seven Days Battle. These battles led to crucial Confederate tactical victories, but they were cut short on the sudden arrival of General Stonewall Jackson. With this reinforcement, McClellan reassembled his troops to a base on the James. Later on, President Lincoln ordered the troops to return to Washington D.C, to reinforce general John Pope’s army in the Second Battle of Bull Run and Northern Virginia Campaign.