| Operation Shingle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Military Leaders | |||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| Initially: 36,000 soldiers and 2,300 vehicles Breakout: 150,000 soldiers and 1,500 guns |

Initially: 20,000 German soldiers + five Italian battalions (4,600 soldiers) Breakout: 135,000 German soldiers + two Italian battalions |

||||||

| Casualties and Deaths | |||||||

| Total: 43,000 casualties 7,000 killed 36,000 wounded or missing |

Total: 40,000 casualties 5,000 killed 30,500 wounded or missing 4,500 prisoners |

||||||

| Part of World War II | |||||||

Operation Shingle is the name given to an amphibious landing by the Allies in Italy during World War II. It took place on January 22, 1944, under the command of United States Major General John P. Lucas. The object, which was successfully achieved, was to land sufficient forces to outflank the Germans along the Winter Line and set up an assault on Rome itself. The fighting which resulted after the landing is usually referred to as the Battle of Anzio.

Background

The Allies had launched their invasion of Italy in September 1943, with U.S. and British troops powering up the Italian peninsula before being halted at the Winter Line – also known as the Gustav Line – just before they entered the town of Cassino. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring had managed to mount a strong defensive force, which the Allies were not able to break through. The commander of Italian Allied forces, General Harold Alexander of the United Kingdom, paused to take stock and to consider his options.

Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, urged that an effort should be made to break the deadlock by means of what he referred to as Operation Shingle. This would involve Allied landings taking place behind the Winter Line, close to the town of Anzio. The U.S. Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, was initially unimpressed by Churchill’s suggestion and refused to consider it. However, Churchill appealed over Marshall’s head to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and won his support for the initiative.

Operation Preparation

The details of the plan were that Lt. General Mark Clark, in command of the American Fifth Army, would attempt to lure Axis forces south by mounting an assault on the Gustav Line. Meanwhile, the VI Corps under Major General John P. Lucas, after landing at Anzio, would attempt to endanger the German rear by means of a movement through the Alban Hills to the northeast. The Allies calculated that if the Germans did not react, the newly landed troops would be available to mount an assault on the Italian capital – but if they did respond, then the Gustav Line itself would be so weakened as to make its continued defense much harder.

The details of the plan were that Lt. General Mark Clark, in command of the American Fifth Army, would attempt to lure Axis forces south by mounting an assault on the Gustav Line. Meanwhile, the VI Corps under Major General John P. Lucas, after landing at Anzio, would attempt to endanger the German rear by means of a movement through the Alban Hills to the northeast. The Allies calculated that if the Germans did not react, the newly landed troops would be available to mount an assault on the Italian capital – but if they did respond, then the Gustav Line itself would be so weakened as to make its continued defense much harder.

Preparations for the operation continued, and Alexander wanted Lucas to make a quick landing and immediately launch an offensive in the Alban Hills. However, the final orders given by Clark to Lucas were much less urgent, allowing Lucas considerable flexibility in his timing. Some historians suggest that this betrayed a lack of confidence in the plan from Clark, in that he believed such an attack would require a considerably larger force. Lucas was also unhappy with the plan as it stood, and felt that he did not have sufficient numbers of troops with which to go ashore. As the date for the launch of the plan approached, he went so far as to compare it to the Gallipoli campaign, an infamous military disaster in World War One – and one which Churchill himself had also devised.

The Landings

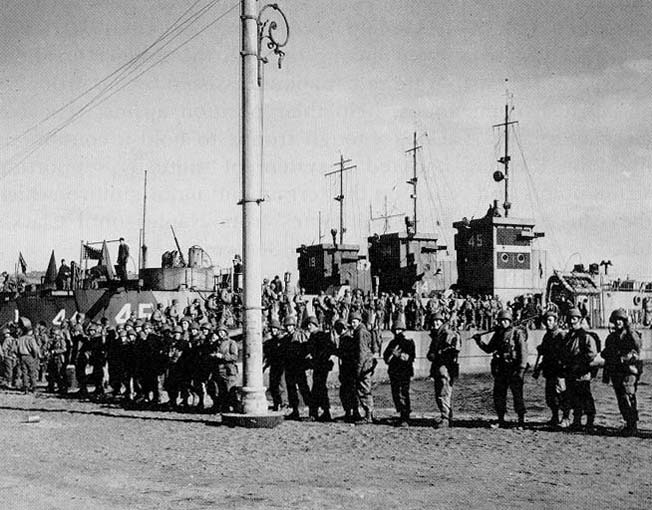

Although there remained serious doubts among the senior commanders on the ground, Operation Shingle went ahead as planned on January 22, 1944. Three Allied forces made landings: the British 1st Infantry Division was the most northern, with the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division making its landing to the south of Anzio.

Although there remained serious doubts among the senior commanders on the ground, Operation Shingle went ahead as planned on January 22, 1944. Three Allied forces made landings: the British 1st Infantry Division was the most northern, with the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division making its landing to the south of Anzio.

The port itself came under assault from the American 6615th Ranger Force. On their initial landings, the Allied armies encountered less resistance than they had anticipated, which allowed them to begin their push into the interior quite quickly.

By the end of the day, the Allies had control of a beach-head two or three miles wide; they had landed around 36,000 men by this time. Although there was some temptation to mount a rapid assault on the German rear, Lucas decided instead that he would concentrate on increasing his perimeter’s strength.

Both Churchill and Alexander were unhappy with this lack of an advance, as they felt that it diminished the usefulness of the operation as a whole. Lucas, however, believed that the superior numbers of the enemy made his actions the correct choice.

Most authorities believe that while Lucas was justified in being cautious, he nevertheless should have tried to push inland rather more quickly. Kesselring, upon being told about the Allied landings, immediately sent mobile reaction units to the scene. He also asked for, and received, reinforcements numbering six divisions from the German High Command.

Kesselring had at first believed that the landings were not containable, but he modified his views upon seeing the inaction of Lucas. By January 24, there were 40,000 men facing the Allied lines in prepared positions.

Later stages and Aftermath

Churchill’s irritation at Lucas’s inactivity continued, and a letter he wrote to Alexander prompted the latter to visit the beach-head on February 14 and tell Lucas a breakout should be mounted as soon as this was doable. Lucas himself displayed his own irritation in his diary the following day, stating baldly that there was “no military reason for Shingle.”

One week later, Clark moved to replace Lucas with his deputy, Lucian Truscott. Lucas was relegated to that deputy status, and was told that his future role would be in the United States rather than in front-line combat.

Conditions remained difficult for the Allied forces, and for several months they were unable to mount the desired breakout. This finally occurred in May, when intense fighting took place near the Gustav Line. In just one day, the U.S. 1st Armored Division suffered over 950 casualties, the highest figure for a single day’s fighting sustained by any American division in the entire war.

Despite these losses, the breakout was a success and the Americans steadily advanced on Rome. Hitler, wanting to avoid another Stalingrad, ordered that Rome be declared an open city, and Clark himself entered the capital on June 4.

Operation Shingle remains controversial to this day, especially concerning Lucas’s initial reluctance to attack. Churchill, in his memoirs, repeatedly blames the lack of quick success for the operation on Lucas, although some of this bitterness may have been related to Clark’s insistence that the final relief of Rome in June should be an entirely American affair.

Kesselring, writing after the war, supported Lucas’s view that the invaders were lacking the strength of numbers for victory in the way imagined by Churchill to be a realistic prospect. Even Alexander conceded that the way events actually turned out was probably the best outcome for the Allies in the long run.