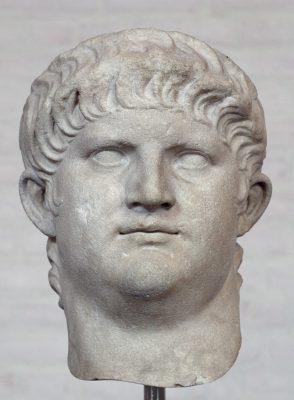

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, more famously known as Nero, was born in Italy on December 15, 37 A.D. He was the son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, who died when Nero was two years old. His mother, Agrippina the Younger, was banished by the emperor Caligula when her husband died. She would later be reunited with her son when Caligula died and was succeeded by Claudius. Agrippina would marry Claudius, who would adopt Nero and eventually choose him as his heir instead of his son, Britannicus. In 53, Agrippina would arrange for Nero to marry Claudius’ daughter, Octavia.

Rise to the Throne

In the year 54, Claudius died, believed by some to be by poisoning, through Agrippina’s maneuverings. The seventeen-year-old Nero became emperor with three trusted people at his side — his mother, the philosopher Seneca, and the praetorian prefect Burrus. Agrippina’s influence over her son soon manifested on coins, where her face appeared alongside her son’s. She did not hold back on her domineering ways towards Nero, prompting the historian Cassius Dio to write that Agrippina “managed for him all the business of the empire…she received embassies and sent letters to various communities, governors, and kings …”

The Murder of Britannicus

The wise Seneca persuaded Nero that it would be best to free himself from his mother’s power. Angered at this, Agrippina argued that Britannicus should be the heir to the throne. At the same time, she criticized Nero for his romance with his friend’s wife, Poppaea Sabina.

Not long after this, Nero had Britannicus poisoned at a dinner party. As Britannicus convulsed, Nero explained to the party attendees that Britannicus was just having an epileptic fit, and that he had been suffering from it since childhood. Britannicus died months later.

The Murder of Agrippina

After Britannicus’ death, Agrippina’s influence on Nero seemed to have weakened, and her face disappeared from Roman coins. Nero then decided to finally take her out of his life. He spread information that Agrippina was plotting to assassinate him. He ordered the boat she was sailing on to be sunk so that she would drown. Agrippina, however, made it to shore, and so Nero later had her stabbed to death at her villa. Nero feared serious repercussions following this but was glad when the Senate congratulated him for eliminating risk to his life.

The Murder of Octavia and Poppaea

Octavia failed to bear Nero a child, and in the year 62, he divorced her and falsely accused her of adultery. He exiled her to the island of Pandateria, and later had her suffocated in a steam bath. She was then beheaded, and her head presented to Poppaea. Afterward, Nero married Poppaea, and they had a daughter who lived for only three months. Nero had Poppaea pregnant again in 65, but she died. Some historians say Nero kicked her in the belly because she was spending too much time at the races, but other historians believe she died due to complications from a miscarriage.

Nero and the Fire

On July 18, 64, a fire ignited in the Circus Maximus that would spread and destroy houses, temples, and public buildings. Some ancient writers say Nero started the fire in order for him to reconstruct the whole area. Other historians doubt this, pointing out that much of the city was constructed out of flammable materials and, naturally, was always prone to fires. The fire raged for ten days, burning down ten districts.

Nero was in Antium at the time but rushed back to Rome when he heard the news. Contrary to popular stories, Nero did not play the fiddle while Rome burned, as the fiddle did not exist in his time. He may have played another instrument or have sung, but the historian Tacitus asserted that there were no eyewitness accounts on the matter. Nero knew the public suspected him of starting the fire. When the inferno ceased, he placed the blame on the Christians, who were at that time, looked at by the public as members of a strange cult.

Tacitus wrote, “Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.”

The cause of the fire may never be known. It is clear, though, that Nero had constructed a golden palace, called the Domus Aurea, on the area that the fire had razed. The palace’s entrance was said to have a bronze statue of Nero that stood 120 feet high.

Downfall

Financial troubles hounded Nero’s final years. The state treasury had been depleted by reconstruction costs in the city, revolts in Britain and Judea, and continuing conflicts with Parthia. Left with no other options, Nero reduced the silver content of the denarius by 10 percent. Afterward, he uncovered an assassination plot against him and ordered the execution of several senators and prefects. Seneca was also accused of having involvement in the conspiracy, and Nero ordered him to commit suicide. Seneca accepted his doom, and his wife chose to share his fate. Both opened their veins and died a slow death.

After this, Nero decided to take a vacation in Greece and participate in the Olympic games. Emperors were not allowed to partake in the games, but Nero changed this rule. Because he regarded himself as an artist, he ordered the addition of events such as acting and singing and then performed in these events. People felt insulted by what Nero had done to the events, especially when he was awarded for his artistic presentations.

The Roman people’s support for Nero quickly began to erode. In the year 64, a governor in Gaul named Julius Vindex declared his rejection of Nero’s rule. He then announced his backing for Galba, a governor in Spain, as emperor. Although Vindex’s forces were defeated by Nero’s soldiers, the Praetorian Guard and the Senate shifted their support to Galba. Terrified of being executed, Nero drove a dagger into his throat. His final words were, “What an artist dies in me!”

Nero’s mistress, Acte, had the former emperor buried in the Mausoleum of the Domitti Ahenobarbi. Centuries after his death, Nero’s name would become synonymous with matricide, depravity, and megalomania.