The Marco Polo bridge incident of China in 1937 is commonly regarded as the start of a major war between then Imperial Japan and the Republic of China. What started as a minor skirmish quickly escalated into a full-scale war between the two nations. In the years of brutal and bloody war that followed, more than a million soldiers would be killed on both sides, and hundreds of thousands of civilians would lose their lives.

The Marco Polo bridge incident of China in 1937 is commonly regarded as the start of a major war between then Imperial Japan and the Republic of China. What started as a minor skirmish quickly escalated into a full-scale war between the two nations. In the years of brutal and bloody war that followed, more than a million soldiers would be killed on both sides, and hundreds of thousands of civilians would lose their lives.

Background

The Marco Polo Bridge, also called the Lugou Bridge, is located in the Chinese city of Wanping, which is in the vicinity of present-day Beijing. The bridge is a large granite structure of 11 arches that spans the Yongding River. It is a centuries old structure, last restored in the late 1600s by the emperor of an ancient Chinese dynasty.

The bridge was a strategic location because it was then the only link between Beijing and an important region to the south controlled by another powerful faction, the Chinese Nationalist Party. Gaining control of the bridge, then, meant significant control of the city of Beijing and the surrounding territories.

During the time leading up to the bridge incident, there were already a large number of Japanese troops stationed in area. The Japanese were taking advantage of loop-holes in Chinese policy which dated back to the Boxer Protocol of 1901. This policy allowed certain foreign nations to place their own troops along an important railroad leading to Beijing so that communications could be maintained between the various governments who had an established presence in China.

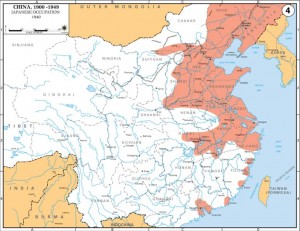

The policy was meant to allow only a small number of foreign personnel but the Japanese stationed between 7,000 and 15,000 troops around the Marco Polo bridge area. In previous years—since 1931—Japan had been attacking and absorbing large chucks of the Chinese continent, gobbling up a number of territories through military conquest. Although the Chinese and Japanese governments were nominally at peace in 1937, the situation remained fluid and unstable.

Imperial Ambitions

The Japanese had been conducting long-term policies of imperialism and expansion. It was no secret that they intended to eventually control all of China. Thus, many historians believe that the skirmish which led to the Marco Polo bridge incident was agitated intentionally, with flimsy excuses manufactured by the Japanese as a pretext to open another full-scale war with the Chinese.

A Skirmish Becomes a Battle

In July of 1937, the Japanese began conducting nighttime military maneuvers in the regions surrounding the Marco Polo bridge. The Chinese objected to this but were not eager to create an incident. Nevertheless, they requested that local residents receive advanced notice for their nighttime military maneuvers from Japanese authorities. The people of the countryside were frightened and concerned that yet another Japanese invasion was starting. Therefore, the request was made of the Japanese to let local officials know these were merely training exercises.

In July of 1937, the Japanese began conducting nighttime military maneuvers in the regions surrounding the Marco Polo bridge. The Chinese objected to this but were not eager to create an incident. Nevertheless, they requested that local residents receive advanced notice for their nighttime military maneuvers from Japanese authorities. The people of the countryside were frightened and concerned that yet another Japanese invasion was starting. Therefore, the request was made of the Japanese to let local officials know these were merely training exercises.

The Japanese agreed, but quickly reneged on their promise. They once again began conducting surprise maneuvers at night, and at one point, moved their infantry close to a contingent of Chinese military forces. The surprised Chinese began directing small weapons fire at the Japanese, and they fired back. During this incident a Japanese soldier went missing. The next day, the Japanese accused the Chinese of taking him captive and demanded the right to conduct a search for the soldier in Chinese territory.

The Chinese countered by offering to conduct their own search and invited a Japanese officer to observe. The Japanese agreed, but before this plan could be carried out, a Japanese infantry unit attacked the city of Wanping. This attack was repulsed by the Chinese. Hostilities ceased for the moment, but the tension had been raised to an extreme level.

The Incident Escalates

The Marco Polo bridge incident may have ended there. However, both sides began amassing large numbers of troops in the area. Communication between the Chinese and Japanese became increasingly frustrating and belligerent. A full-scale war broke out on July 20 when the Japanese began shelling Wanping with heavy artillery. On July 25, both armies committed to all-out war.

The Chinese launched a massive assault on Japanese positions, but were unsuccessful in repulsing them. The fighting was intense and deaths and casualties occurred in large numbers. The Chinese were forced to retreat some distance away to the other side of the Yongding River. And, as the Japanese government had ordered its forces to advance only as far as the Yongding River, the fighting might have ended at this point.

Over the next several days, however, a number of complex political maneuvers and negotiations involving various factions of the Chinese government lead to the Battle of Beiping-Tianjin, in which the Japanese won a decisive victory. A few weeks later, in August, the two nations fought the Battle of Shanghai, which resulted in another victory for the Japanese. More than a quarter of a million Chinese and 70,000 Japanese were killed in the Battle of Shanghai, making it among the bloodiest battles in world history.

The Battle of Shanghai was the first of 21 major battles in the Second Sino-Japanese War. More than 1.3 million Chinese would be killed and more than 1 million Japanese. The war ended with the close of World War II after the Japanese surrendered to Allied Forces following the atomic bomb attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Following their surrender, the Japanese lost all of the lands they had won in China since 1931.

A Dark Period

The First Sino-Japanese War began in 1931 and resulted in the loss of a major portion of territory and cities to the Japanese. Following this, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident ignited the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

One of the most shocking episodes that followed the Marco Polo bridge incident was the Japanese conquest of the city of Nanking. Here, more than 100,000 Chinese civilians were brutally slaughtered by Japanese soldiers. In the process, they committed unimaginable war crimes, including the rape of tens of thousands of Chinese women, who were then murdered and mutilated. Other atrocities, such as the killing of babies, the dismemberment of innocent civilians, and even cannibalism, were rampant among the Japanese forces.

The Marco Polo bridge incident is considered a moment of national shame and horror for the Chinese people, and is certainly among the darkest periods in world history.