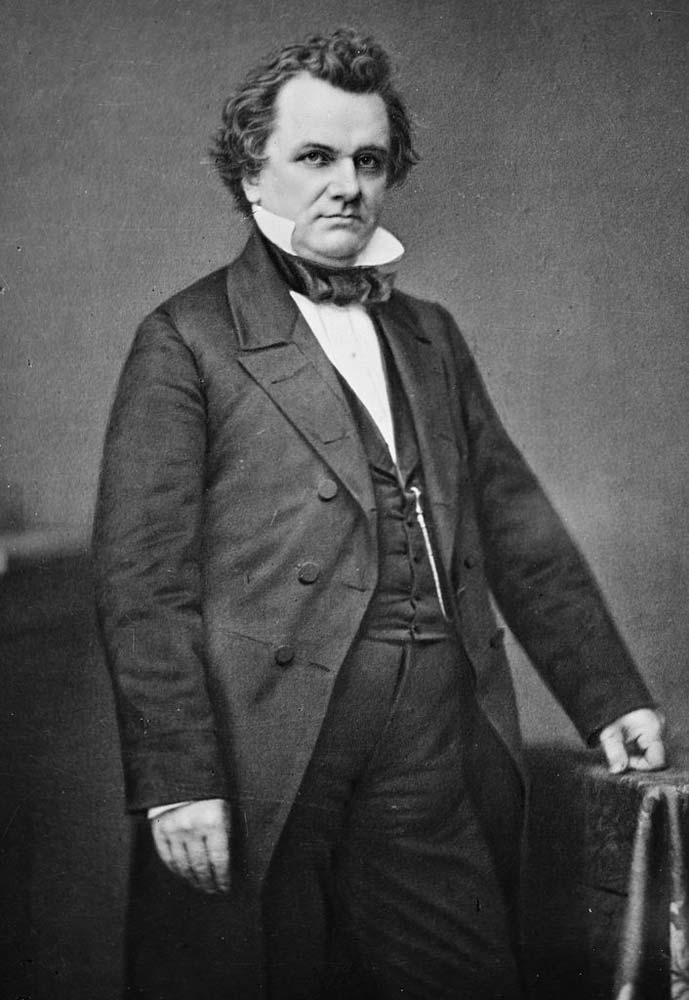

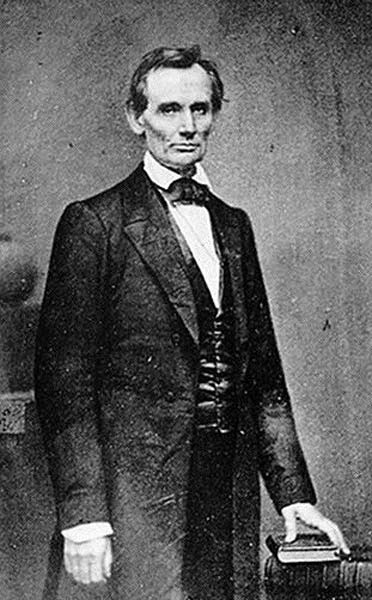

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln was running on the Republican ticket for U.S. Senator of Illinois. His opponent was Democrat Stephen Douglas. As part of the campaign, the two candidates agreed to a series of nine debates (one in each Congressional district) across Illinois. They ended up holding seven debates because Lincoln and Douglas spoke separately in Chicago and Springfield.

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln was running on the Republican ticket for U.S. Senator of Illinois. His opponent was Democrat Stephen Douglas. As part of the campaign, the two candidates agreed to a series of nine debates (one in each Congressional district) across Illinois. They ended up holding seven debates because Lincoln and Douglas spoke separately in Chicago and Springfield.

Different Times, Different Rules

At the time, U.S. Senators were not elected by popular vote of the people. Rather, Senators were appointed to their positions by the members of the state legislature. This meant that whichever party won the most seats at the state level would get its choice of who to send on to Washington.

Even so, debating before and appealing to the general public was still important for the Washington-level Senate candidates. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates drew gigantic crowds, even many people from out of state, because their focus was on the very hottest, most contentious issue of the day: Slavery.

The debate format was strenuous by today’s standard. The first speaker was given a full hour to speak uninterrupted. His opponent spoke next for 90 minutes. Then the first speaker was given an additional 30 minutes to rebut.

Freedom vs. Slavery

Lincoln made a passionate argument for the banishment of slavery. Douglas argued much the opposite. He favored a plan wherein each state should be allowed to form its own policy on slavery while Lincoln argued for a national ban that would include all states, and thus eliminate slavery from America.

Interest was so keen in the debates that local newspapers transcribed them word-for-word for the reading public. In those days, most newspapers were heavily partisan. Thus, a Republican paper would print cleaned up and well-edited versions of Lincoln’s speech, while printing the words of his opponent as they had been spoken, with all the common grammatical slips and mistakes of spoken language. Democratic newspapers did the same.

Free But Not Equal

It is interesting to note that while Lincoln favored freedom for black slaves, he also vigorously denied that he was an abolitionist. That is, he argued that while slaves would be free, they still might be considered inferior to whites. Lincoln said that he considered the white race superior to blacks, but that this was a non-issue in terms of whether black should be slaves or free.

He also said that he did not favor “a social and political equality” that would place blacks and white on an equal level. He did not favor the mixing of races in terms of marriage. Rather, he said that blacks should be free to live their lives as they please, and that white people could “ignore them” if they wanted to.

Douglas countered by attempting to paint Lincoln as a total abolitionist. Despite the distinctions he was making, Douglas said that Lincoln’s position on blacks and slavery would amount to making them equal to whites in all ways within American society.

Douglas Wins

After seven debates, the elections were conducted and Douglas and his Democrats won a very narrow majority of seats in the Illinois legislature, even though they lost slightly the overall popular vote. That meant Douglas was sent on to Washington as U.S. Senator. But Abraham Lincoln was to get the last laugh.

After the debates, Lincoln gathered the text of all his debate speeches, edited them and issued them in the form of a book. The book became popular reading throughout the United States. The book did much to bolster Lincoln’s image on a national scale. Upon losing his bid for the U.S. Senate, he ran for President of the United States successfully and was elected to that office in 1860.

Debates Lasting Influence

The Lincoln-Douglas debates have been studied ever since as examples of excellent debating. They are frequently cited as examples of rhetorical eloquence and use of style in language. Many of the central political and philosophical issues of American politics were more sharply defined as the result of the debates.

The Lincoln-Douglas debate also serve as a model for a specific kind of debate competition still taught in high schools, colleges and universities today. However, the format of speaking for an hour, then 90 minutes, followed by a 30-minute rebuttal is rarely used. Modern debates tend to involve more rigorous and frequent exchange between opponents who rebut each other point by point, each speaking for two or three minutes at a time.

The original Lincoln-Douglas debates remain today as a central aspect of American history. They mark a turning point for how political public discourse is conducted – the debates set a standard of excellence that has served as a model ever since.