The Lateran Treaty was an accord of 1929 between Italy and the Vatican. It was signed in February 11th of that year, and ratified in June 7th by the Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy. The treaty aimed to settle once and for all what was known as the “Roman Question”, regarding relations between the Vatican and the former Papal States that had become modern Italy. Although the Italian government in 1929 was that of Benito Mussolini‘s Fascist regime, the treaty was accepted unchanged by the democratic post-war government.

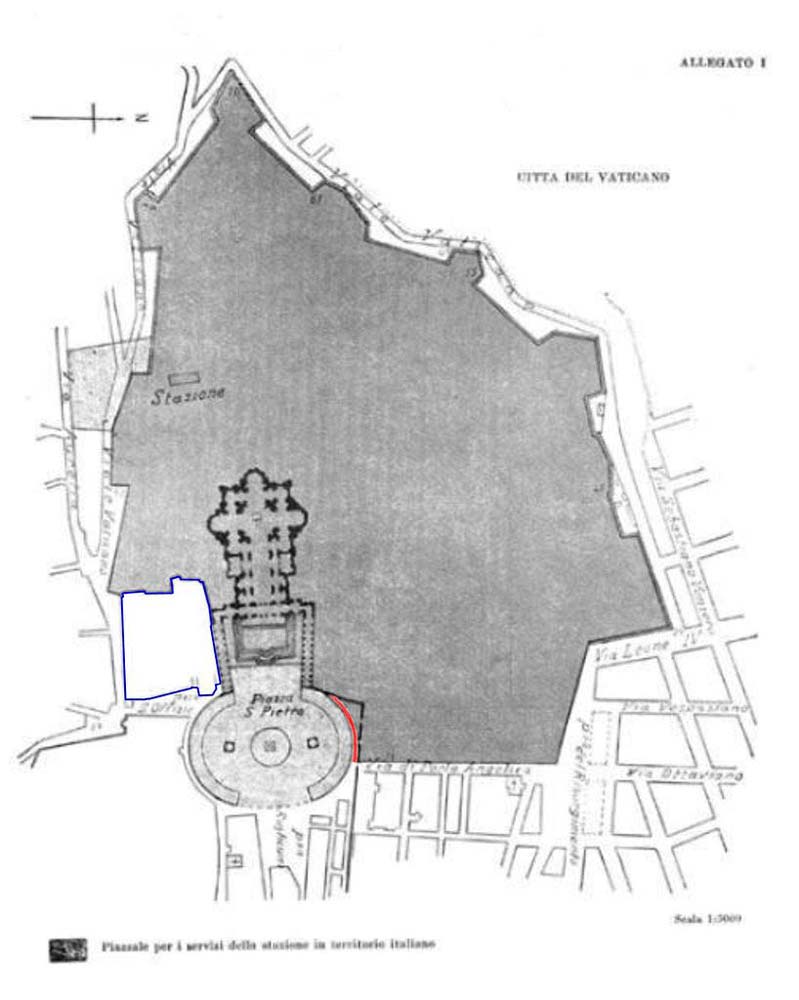

The accords were made up of two documents. The first was a political treaty; this acknowledged the legitimacy and sovereignty of the Holy See’s administration within the new State of Vatican City. The second formalized relations between the Italian government and the Roman Catholic Church. The political pact was accompanied by four annexes. These provided a map of the Vatican City’s territory, plans and lists of which buildings would be exempt from taxation and expropriation, and what was intended to be a final financial settlement to compensate the Holy See for its loss of other territories and goods.

Background

Despite the unification of Italy during the middle of the 19th century, the Papal States stayed outside the process. In 1860, Italy occupied Romagna, which made up the eastern portion of the Papal States, thereby leaving Latium as the only one still under Papal control. Ten years later, even this – including the city of Rome – was to be annexed by the Italian state. For sixty years thereafter, a hostile relationship was to characterize dealings between Italy and the Papacy, with the Pope’s own status becoming unclear and often referred to as “the Roman Question.”

In 1926, negotiations were begun between the Vatican and Italy with the aim of solving these difficulties. These were finally agreed three years later. Among their provisions was a guarantee that the Holy See could maintain full sovereignty independent from Italy itself. In return, the Pope agreed that he would remain neutral in international affairs, and would not intervene to mediate in any controversy without the support of all interested parties. Italy, meanwhile, reaffirmed that Roman Catholicism would remain the single religion of the Italian nation.

Financial Terms

The sum paid to the Holy See in compensation for its material loss to Italy was in fact relatively small. Italy had proposed in 1871 that it would pay 3.25 million lire per year to the Papacy, but that the Pope – at that time, Pius IX – would only be granted use of the Lateran and Vatican palaces, not full sovereignty over them. These terms were therefore unacceptable to the Holy See, which refused to countenance Italy’s proposal. For two generations, successive Popes painted a picture of themselves as prisoners inside the Vatican, unable to leave because of Italy’s intransigence.

The signing of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 constituted a considerable propaganda coup for Mussolini, who proceeded to make the most of it. Among his most physically visible actions was the commissioning of the Via della Conciliazione. This road, which was begun in 1936 but not finally completed until well after the end of World War Two, was intended as both a physical and a symbolic link between the center of Rome and the Vatican City itself. The relatively smooth continuance of the treaty into post-war Italian times is also illustrated by its inclusion in the 1947 Italian Constitution.

Revision and Controversy

In 1984, the second document of the treaty, regulating the place of the Roman Catholic Church in the Italian state, was repealed, allowing a number of other religious groups to benefit from a new type of income tax. Italy also ceased to recognize the award of noble titles and orders of knighthood which had been made by the Holy See, as well as the ability of the Italian government to object to potential bishops simply on political grounds. Later, in 2008, the Vatican announced that – after a dispute surrounding an Italian right-to-die case – the Holy See would no longer adopt all new laws of Italy.

The major controversy surrounding the Lateran Treaty during Italy’s Fascist years came in 1938, when Mussolini’s government passed laws banning Jews from marrying non-Jews. Since this directly affected Roman Catholics, the Vatican considered that the section of the treaty giving the Church the right to regulate any marriages in which Catholics were involved had been breached. The Holy See also protested that the agreement had specified that Roman Catholic marriages would automatically be accepted as valid by the Italian civil authorities. Nevertheless, the marriage laws remained in force.