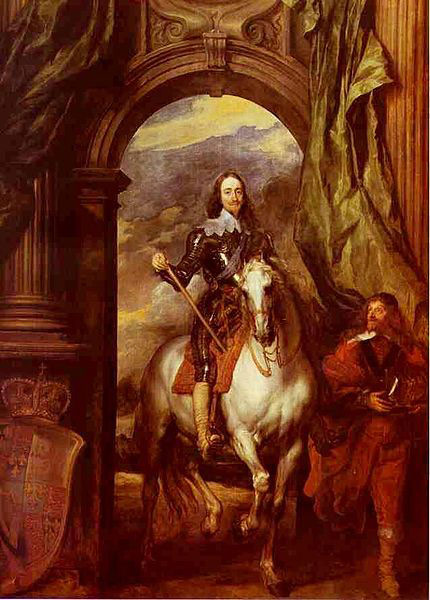

King Charles I (Nov 19, 1600 to Jan 30, 1649) is remembered in history as the King whose obstinacy led to his execution and brought down the Monarchy, which turned England briefly into a republic.

King Charles I (Nov 19, 1600 to Jan 30, 1649) is remembered in history as the King whose obstinacy led to his execution and brought down the Monarchy, which turned England briefly into a republic.

Early Years

Charles was the second son of King James VI of Scotland and Princess Anne of Denmark. He was born in Fife, Scotland. In 1603, after the demise of Queen Elizabeth I, his father succeeded to the throne of England as King James I. In his childhood, Charles hero worshipped his brilliant elder brother Prince Henry. Henry died when Charles was only 12 years old. Charles and his sister Elizabeth mourned the loss of their beloved brother, and this created a deep bond between the siblings, a bond which was to have deep political ramifications over the years. Though born weak, Charles used tremendous will power to overcome his shortcomings and became skilled at riding and hunting. His tastes were sophisticated and he had an innate belief that a King ruled the country by “divine right.”

His sister Elizabeth was married to Frederick V, the Elector of the Palatinate, a leading state in the German Protestant Union. Protestant nobles chose Frederick and Elizabeth to be the King and Queen of Bohemia, over the claim of the Hapsburg Emperor. This was the trigger for the Thirty Years’ War which engulfed Europe. Frederick was defeated in battle and exiled from the Palatinate.

Initial Years of the Throne

King Charles I succeeded his father King James I as the second Stuart King in 1625. He ascended the throne at a time when there was great pressure from Protestants to take up arms against the Catholic powers of Europe, mainly Spain. Though James I believed in peace and diplomacy, England had became embroiled, in what is known as the Thirty Years’ War (1618 to 1648), which was raging in Europe between the Catholic and Protestant countries.

King Charles I succeeded his father King James I as the second Stuart King in 1625. He ascended the throne at a time when there was great pressure from Protestants to take up arms against the Catholic powers of Europe, mainly Spain. Though James I believed in peace and diplomacy, England had became embroiled, in what is known as the Thirty Years’ War (1618 to 1648), which was raging in Europe between the Catholic and Protestant countries.

King Charles I allowed England’s foreign policy to be directed by a deeply unpopular Duke of Buckingham. The Duke used bad judgment and launched a series of wars against Spain and France as a means of indirectly helping Frederick and Elizabeth to regain the Palatinate. The expeditions proved disastrous. When the Parliament tried to impeach the Duke, Charles dissolved the Parliament on two occasions. However the need for funds for his war agenda forced him to call a third Parliament. In 1628, Charles detractors forced him to accept the Petition of Rights, which prevented arbitrary use of the King’s powers. Though he reluctantly accepted the petition, he paid only lip service to its provisions.

Confrontation with the Parliament

The Duke’s disastrous military misadventures and the King’s religious policies had alienated the King from the Members of Parliament and the common people. The Duke of Buckingham was assassinated in 1628 and the King’s critics stepped up their opposition. Charles responded by dismissing the third parliament in 1629 and imprisoning many of his opponents. The King declared that henceforth he would rule the country alone. The King’s personal rule lasted eleven years and was known as the “Eleven Years’ Tyranny”. Initially it was successful and the people enjoyed a measure of peace and prosperity. Charles made peace with Spain and France in 1630. By 1635, with increasing trade and commerce, the finances of the country were in good shape.

However, without a Parliament, King Charles had no means to legally enforce taxes and had to resort to obscure and unpopular methods to raise money, such as forced loans, sale of commercial monopolies and ship money. These unpopular measures, coupled with his controversial religious policies, alienated even his ardent supporters among the nobility. To add further unpopularity, the King used the ‘Star Chamber’, which was initially supposed to be a court of appeal but in reality was the opposite, to torture his opponents and suppress dissent. In the minds of the people, all this added up to the King’s misuse of power during the period of his personal rule.

Religious Policy

King Charles believed in the elaborate and ritualized form of Anglican Church worship. He appointed William Laud as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud believed in strict application and obedience to Church doctrine. He also used the Star chamber to torture Puritans, who were opposed him on the grounds that the Anglican Church dogma was too similar to that of the Roman Catholic Church. The King’s marriage to the French Catholic Princess Henrietta Maria and her open practice of Catholism caused apprehension in the minds of the Protestant population. Though Charles himself was a devout follower of the Anglican Church, his deeply divisive religious policies alienated powerful and influential people like Cromwell. The King, under advice by Archbishop Laud insisted that the three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland conform to Anglican practices. As a backlash to this policy, the Scottish National Covenant was formed against interference in the practice of religion. This resulted in the Bishops’ Wars between England and Scotland. To finance the war, Charles was forced to convene the Parliament in 1640, thus ending 11 years of his personal rule.

King Charles believed in the elaborate and ritualized form of Anglican Church worship. He appointed William Laud as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud believed in strict application and obedience to Church doctrine. He also used the Star chamber to torture Puritans, who were opposed him on the grounds that the Anglican Church dogma was too similar to that of the Roman Catholic Church. The King’s marriage to the French Catholic Princess Henrietta Maria and her open practice of Catholism caused apprehension in the minds of the Protestant population. Though Charles himself was a devout follower of the Anglican Church, his deeply divisive religious policies alienated powerful and influential people like Cromwell. The King, under advice by Archbishop Laud insisted that the three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland conform to Anglican practices. As a backlash to this policy, the Scottish National Covenant was formed against interference in the practice of religion. This resulted in the Bishops’ Wars between England and Scotland. To finance the war, Charles was forced to convene the Parliament in 1640, thus ending 11 years of his personal rule.

Confrontation with the Short and Long Parliaments

The short Parliament of 1640 was bitterly opposed to the King’s policies of Church and State. Rather than taking on the King frontally, the Parliamentarians impeached and sentenced to death the Archbishop Laud and the Earl of Stafford. Charles could not do much to help them.

The next crisis arose when the Irish rose against the English rule. A dispute arose between the King and Parliament as to who should control the Army against the Irish. The King’s attempt to arrest the five leading Parliamentarians opposed to him, resulted in civil unrest which forced the King and his family to flee London in 1642. Both the King and Parliament appealed to the people for support and it culminated in the first civil war. The Parliament, by skillfully raising fears of the King using the Irish to regain control and the ensuing fears of a Catholic resurgence, caused irreparable damage to the Royalist cause. The Royalists were defeated in 1645-46 by a coalition of the Parliament, Scottish Covenanters and a newly formed professional New Model Army.

Trial & Execution

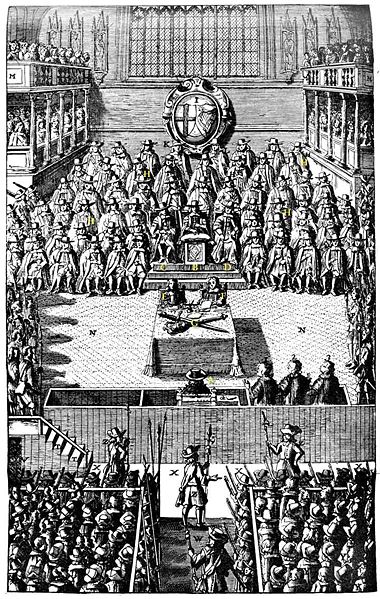

King Charles I surrendered to the Scottish army rather than to the Parliament. In spite of him using devious plots to try and regain power, he was not successful. By his association with foreigners and Catholics he had damaged his position irreparably. The Army was furious with King Charles I for provoking a second war when he had lost the first, which they thought was a clear indication of God’s favor to the Parliamentarians cause.

King Charles I surrendered to the Scottish army rather than to the Parliament. In spite of him using devious plots to try and regain power, he was not successful. By his association with foreigners and Catholics he had damaged his position irreparably. The Army was furious with King Charles I for provoking a second war when he had lost the first, which they thought was a clear indication of God’s favor to the Parliamentarians cause.

In 1649, the Parliament appointed a High Court of Justice to try King Charles I for high treason. Charles refused to recognize the jurisdiction of the court. He was found guilty and sentenced to death on January 27, 1649. He was executed on Jan 30th; bringing to an end a troubled era in English history. The Monarchy was restored in 1660 and remains in place to this day.