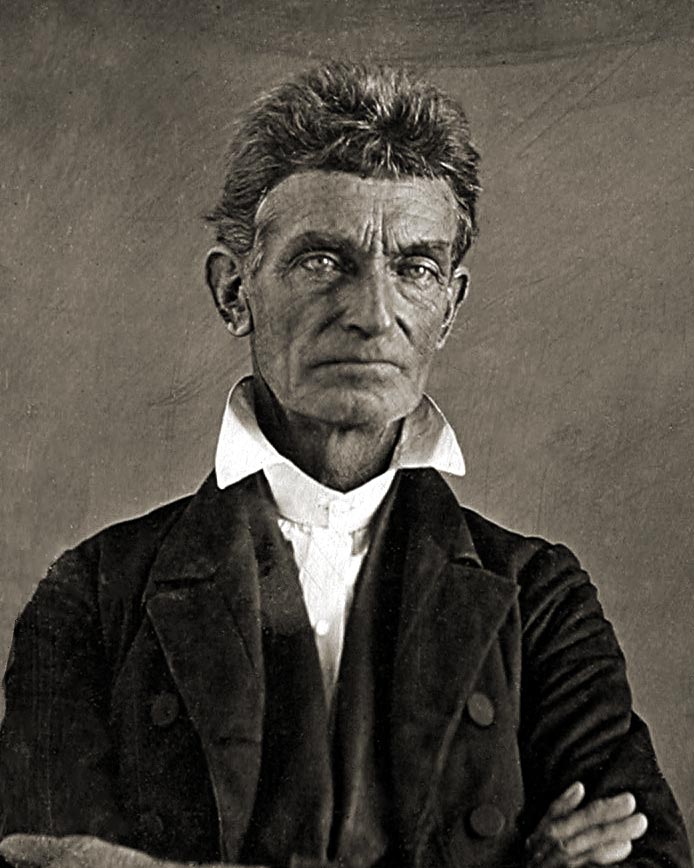

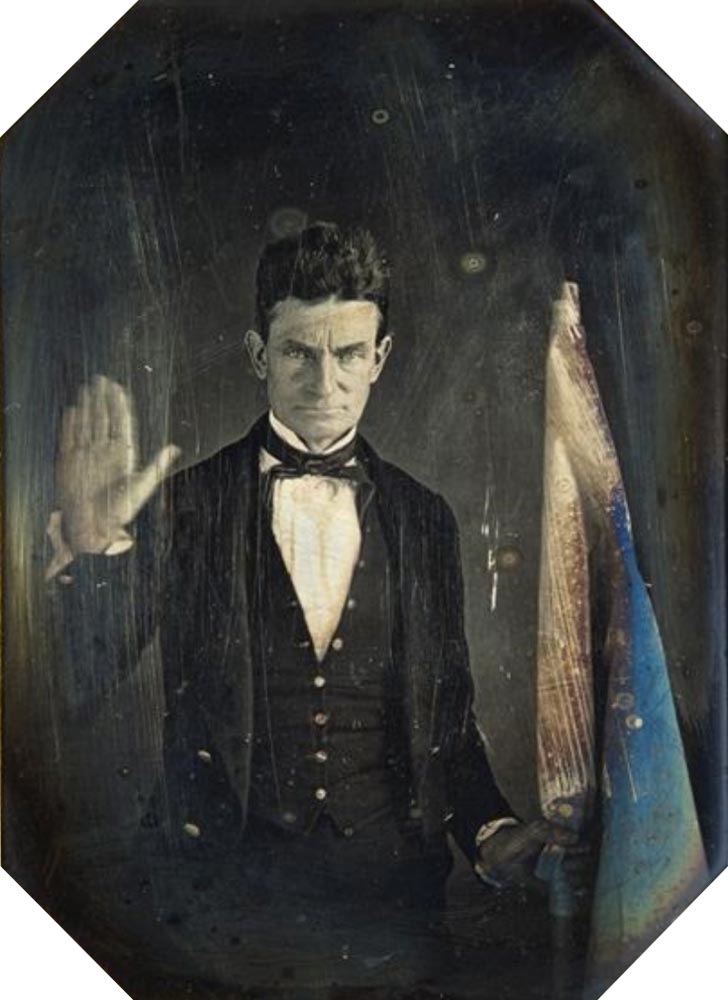

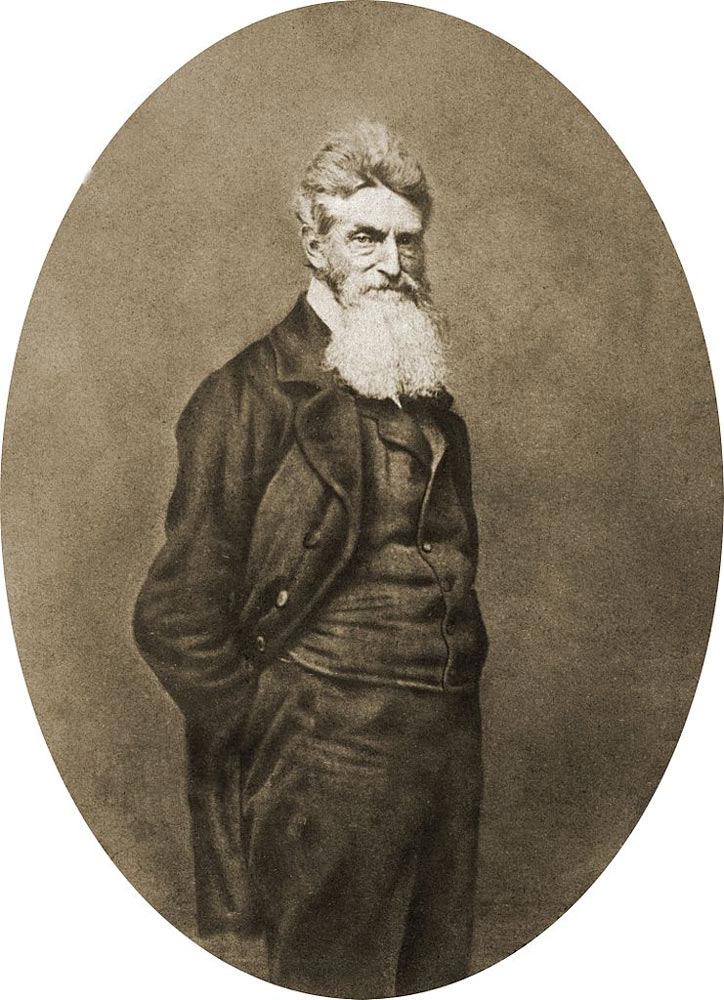

| John Brown | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | May 9, 1800 Torrington, Connecticut |

| Died | Dec. 2, 1859 (at age 59) Charles Town, Virginia |

| Known for | Pottawatomie Massacre Raid on Harpers Ferry |

| Penalty | Hanging |

John Brown (1800-1859) was an American abolitionist in the years just before the American Civil War. He was so strongly opposed to the institution of slavery that he was prepared to use violence to achieve his aims. He is best known for the abortive attack he led on federal troops at Harpers Ferry in 1859, although he had previously been involved in several other violent attacks on supporters of slavery. After the incident at Harpers Ferry, Brown was arrested and executed for treason and murder.

Early Life

Brown was the son of a tanner, born in the Connecticut town of Torrington. Instead of following his father into the leather trade, he decided to go into the church, but before long he had changed his mind and was apprenticed to a tanner himself. At the age of twelve, Brown witnessed at first hand the mistreatment of a black boy, which he later said was the catalyst that sparked his determination to fight an “eternal war” against the institution of slavery. In 1820, he married his first wife, Dianthe, and the couple had seven children together. After her death twelve years later, he married Mary, with whom he had a further thirteen children.

Before he was out of his teens, Brown’s views on slavery had hardened to such an extent that he had become convinced that there was no peaceful way to abolish it. Instead, believed Brown, the slaves could only be freed by force, something which would necessitate a full-scale invasion of the Southern slaving states. However, as a young man still, he was in no real position to put his ideas into practice. Instead, he started several unsuccessful businesses over the next few years, eventually moving with Mary and the surviving children to New York, where he settled on a farm in North Elba.

Before he was out of his teens, Brown’s views on slavery had hardened to such an extent that he had become convinced that there was no peaceful way to abolish it. Instead, believed Brown, the slaves could only be freed by force, something which would necessitate a full-scale invasion of the Southern slaving states. However, as a young man still, he was in no real position to put his ideas into practice. Instead, he started several unsuccessful businesses over the next few years, eventually moving with Mary and the surviving children to New York, where he settled on a farm in North Elba.

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed into law, mandating that slavery’s status should be determined by popular sovereignty and so resulting in control being fought over by those on either side of the debate. Brown toured the eastern states, not only calling for Kansas to abolish slavery but openly agitating for funds for weapons to aid in that cause. In September of that year, he moved again, this time to Kansas itself, saying that he had come to support “the killing of slavery.” Two years later, he led a raid on a settlement at Pottawatomie which resulted in the deaths of five pro-slavery settlers.

Preparing for Battle

Brown was now well-known throughout the country, although opinions on his methods were highly polarized. While raising money in New England in the summer months of 1856, his dedication to the cause brought him support from a number of prominent figures. They assisted Brown in finding not only funds but guns and recruits. Another raid was launched in August, in which Brown’s son Frederick lost his life. Brown himself was not put off by this tragedy, making it clear that he was also prepared to die for what he saw as a crusade to end a grievous sin.

Early in 1857, Brown went to Iowa to speak with abolitionists from the eastern states, and to muster supporters for his plan for an invasion of the South. He sent one of his sons, also named John, to conduct a survey around Harpers Ferry, where there was a federal arsenal. That spring, Brown went to Ontario for talks with his men away from U.S. jurisdiction. He told them that he planned not merely to launch an invasion but to give weapons to the slaves and help them establish a new, free state in which slavery would be utterly prohibited.

Under an alias, Brown went back to Kansas, from where he launched another raid, this time on Missouri. Both that state and the federal government now considered him a criminal, with rewards being posted for his capture. The abolitionist parts of the North, however, saw him as a national hero and showered him with donations.

Under an alias, Brown went back to Kansas, from where he launched another raid, this time on Missouri. Both that state and the federal government now considered him a criminal, with rewards being posted for his capture. The abolitionist parts of the North, however, saw him as a national hero and showered him with donations.

In the summer of 1859, Brown rented a farm a few miles to the north of Harpers Ferry, where he mustered 21 men for training in the final stage of his plan: he would take the arsenal by force and give its weapons to the slaves – although in fact there were few in this sparsely populated area.

The Harpers Ferry Raid

After dark on October 16, 1859 Brown, accompanied by 18 men, started out with a wagon of supplies for Harpers Ferry. They managed to enter the town undetected and capture the watchmen at the armory. However, Brown failed to stop the midnight train, whose crew raised the alarm the following morning. Early the next day, there was a certain amount of gunfire exchanged between Brown’s party and residents of Harpers Ferry, after which soldiers arrived from Charles Town, trapping Brown with his men – most of whom had been wounded – in the engine house of the armory

By that night, a party of 90 marines from Washington, D.C., had arrived, and in the morning they launched an assault on the engine house in which ten of Brown’s party were killed and seven, including Brown himself, captured. He had been wounded by slashes from a marine’s sword and his trial in Charles Town, a week later, took place with Brown lying on a stretcher. The court convicted him of treason, conspiracy, and murder, and sentenced to be executed. He was hanged on December 2, after having given his jailer a note in which he stated, presciently, that only blood would purge America of slavery.

Aftermath

Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry came as a shock to the nation. Ralph Waldo Emerson was among the eminent men who praised his actions, and Brown’s funeral was well attended, but many others – including some abolitionists – were of the opinion that he had committed a wicked crime. Brown’s reputation recovered after the outbreak of the Civil War, in which it became clear that fighting would indeed be necessary to prevent secession of the Southern slaving states. By 1861, the popular song, “John Brown’s Body,” had become popular and ensured that he would become one of the best remembered figures of antebellum abolitionism.