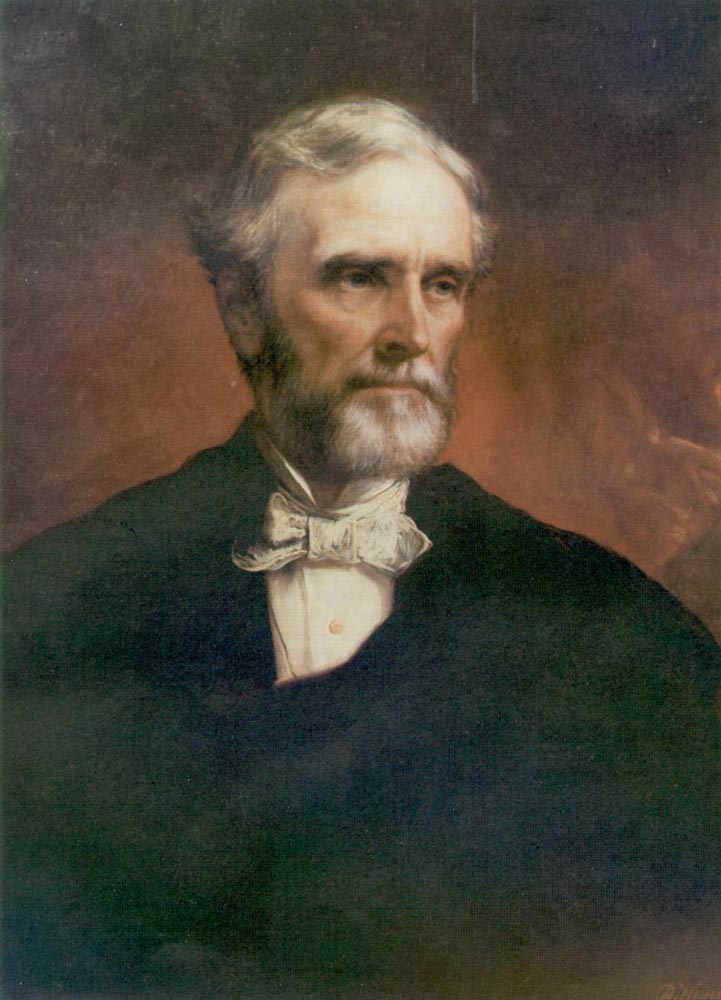

Jefferson Davis was the President of the Confederate States of America from its foundation in 1861 up to the end of the American Civil War in 1865. He was born in Kentucky in 1808, but grew up in Mississippi after his family moved there in 1812 to run a cotton plantation. He graduated from university in Lexington, Kentucky in 1821, and three years later enrolled in the West Point Military Academy, from which he received his commission as a second lieutenant in 1828.

Early Career

He was sent to Fort Crawford in Wisconsin to begin his military career with the 1st Infantry Regiment. It was there that he met Colonel Zachary Taylor and became romantically involved with Taylor’s daughter Sarah. Taylor was unhappy with the liaison because he did not want Sarah to be a military wife. Davis decided to resign his commission, and married Sarah in 1835. The couple went to live at Davis’ brother’s plantation in Warrant County, Mississippi. Shortly afterwards, they were both taken ill with malaria. Davis survived but Sarah died from the disease only three months after they had been married.

Davis received a gift of 900 acres of land from his brother Joseph, and he established the Brierfield Plantation, which by 1845 had 74 slaves working. He had become interested in politics following the death of Sarah and in 1843 he stood as a Democratic candidate for election into the House of Representatives. The following year, he took an active role in the presidential election campaign that James Polk ran.

The Mexican-American War

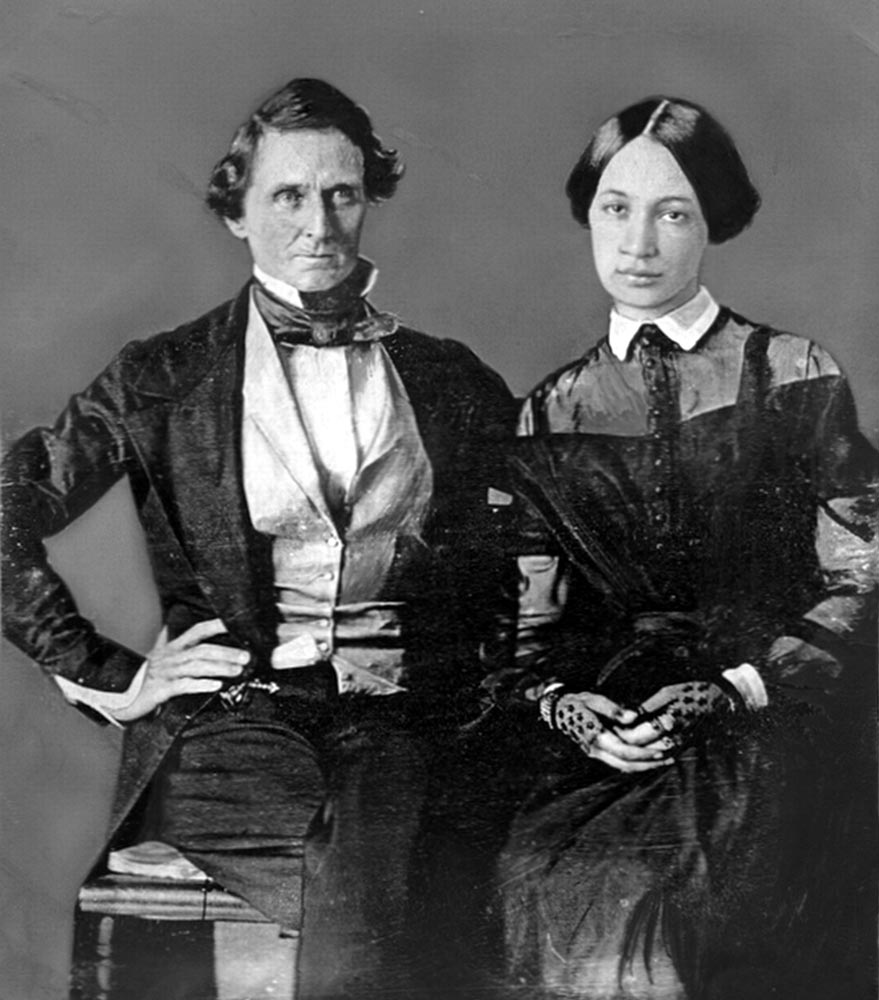

In 1845, Jefferson Davis married for the second time. His bride was Varina Banks Howell, who at just seventeen was twenty years younger than him. Following the outbreak of the Mexican American War in 1846, Davis organized a regiment of volunteers, the Mississippi Rifles and took responsibility for arming and training the troops. In September of that year, he commanded his rifles at the Siege of Monterrey. In February 1847, Davis was injured at the Battle of Buena Vista. He declined an offer from Polk to rejoin the Federal army as a Brigadier General.

Appointment to the Senate

After the death of Senator Jesse Speight in Mississippi, the governor asked Davis to complete the term, an offer he accepted. He was made chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, and was reelected to the Senate at the end of his first term. He resigned his seat to stand unsuccessfully in the election for Governor. He campaigned actively on behalf of Franklin Pierce in the 1852 Presidential election, which Pierce won. Pierce appointed Davis as his Secretary of War. When Pierce was not reelected, Davis also lost his position and stood once again for the Senate in 1857.

After the death of Senator Jesse Speight in Mississippi, the governor asked Davis to complete the term, an offer he accepted. He was made chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs, and was reelected to the Senate at the end of his first term. He resigned his seat to stand unsuccessfully in the election for Governor. He campaigned actively on behalf of Franklin Pierce in the 1852 Presidential election, which Pierce won. Pierce appointed Davis as his Secretary of War. When Pierce was not reelected, Davis also lost his position and stood once again for the Senate in 1857.

Secession

During his political career, he was against secession from the Union. While he believed every state had the constitutional right to secede, he felt that the South was ill prepared for military action by Federal troops, which Davis believed was inevitable following secession.

The election of Abraham Lincoln as President in 1860 led to a rapid change in the political situation. Lincoln had made the abolition of slavery one of his campaign platforms and the Southern states in particular would suffer financial hardship if slavery was abolished.

The election of Abraham Lincoln as President in 1860 led to a rapid change in the political situation. Lincoln had made the abolition of slavery one of his campaign platforms and the Southern states in particular would suffer financial hardship if slavery was abolished.

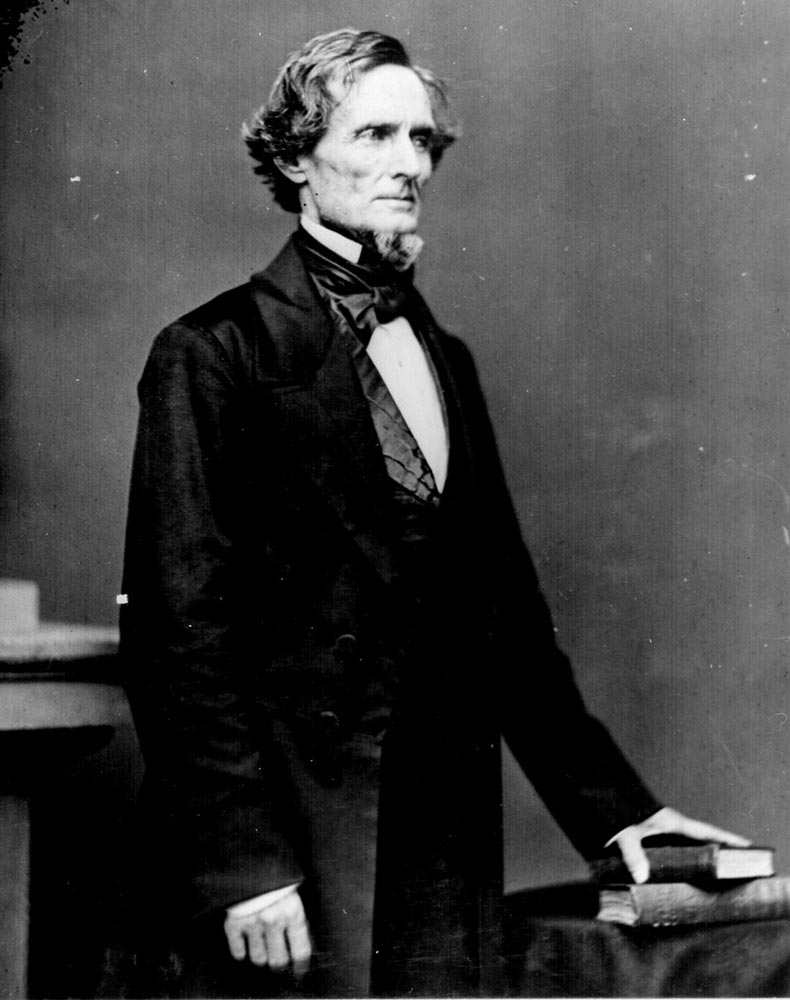

When Davis was informed of the secession of Mississippi in January 1861, he resigned from the Senate, and informed Mississippi Governor Pettus that he was ready to serve in whatever role was required of him. Pettus appointed him as a Major General in the Army of Mississippi. In February, he was appointed as provisional Confederate States President and was eventually elected to the post in November.

In an effort to avert war, Davis tried to negotiate with Lincoln’s government over Union-held forts and other Federal property in the Southern states. The Confederacy offered financial compensation in exchange for the Federal property, and further offered to pay its fair share of the national debt, but the offer was declined. War eventually broke out when Confederate troops attacked Fort Sumter following the refusal of the Union soldiers in it to withdraw.

When the state of Virginia seceded and joined the Confederacy, Davis decided to move the seat of government to Richmond in May 1861, and Richmond would remain as the Confederate seat of power for the duration of the war.

Given his military background and his previous position as Secretary of War, Davis was perfectly placed to understand the difficulties facing the Confederacy. He was convinced that the only way the Confederate States could survive was by concentrating on defensive strategies. He appointed Robert E. Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia and frequently discussed strategy with him.

Criticism

Many military historians feel that it was a mistake for Davis to actively involve himself in military decisions. They feel he would have been better to appoint fit men for the job and concentrate on his administration. They also feel that the scope of Davis’ defensive strategy was too broad, resulting in his resources being over-stretched.

Many military historians feel that it was a mistake for Davis to actively involve himself in military decisions. They feel he would have been better to appoint fit men for the job and concentrate on his administration. They also feel that the scope of Davis’ defensive strategy was too broad, resulting in his resources being over-stretched.

He is also criticized for his military appointments. He seemed to make appointments based on personal friendships rather than military skills and abilities. By the time he appointed Robert E. Lee as supreme commander, the war had been essentially lost.

As a political leader, he failed to generate massive support from ordinary people, who felt that the Confederate government favored the wealthy when raising taxes and supplies to support the war effort. He also had difficulties in persuading state Governors to bring the individual state militias under the command of the Confederate government.

Capture

As the Union victory in the Civil War became inevitable and Federal troops were closing on Richmond, Davis fled with his cabinet to Danville in Virginia. Davis then went to Greensboro in North Carolina. Despite the crushing defeats and Lee’s surrender, some Confederate supporters wanted the war to continue, and proposed the establishment of a Confederate Government in exile in Havana, with Davis retaining the presidency, but nothing came of this.

The Confederate government was dissolved on May 5, 1865 and Davis set out to try to escape to Europe with his family. He was captured on May 10 in Irwin County in Georgia, charged with treason, and imprisoned. After two years, he was released on bail. In February 1869, the treason charge was dropped. He never took an active part in politics again, and died in 1889.