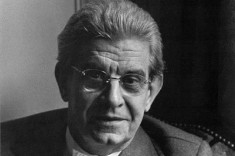

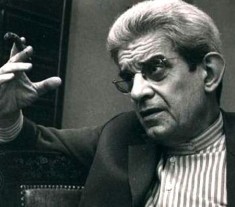

| Jacques Lacan | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Psychologist | |

| Born | Apr. 13, 1901 Paris, France |

| Died | Sep. 9, 1981 (at age 80) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

Jacques Lacan was a French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. He was strongly associated with the post-structural movement in the 1960s and 1970s. He was known for his regular seminars, some of which were later collected into book form, but he was also a highly controversial figure.

Indeed, some of his contemporaries rated him the most divisive figure in the field since Sigmund Freud. As well as psychoanalysis, Lacan was important to a wider range of other theoretical disciplines, including criticism, philosophy, and sociology.

Early Life

Lacan was born into a middle-class Catholic family in Paris on April 13, 1901. He worked hard at school and distinguished himself in the field of philosophy. After leaving, he went on to medical school where, in the 1920s, he studied with Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault.

University Years

He spent time with patients who suffered from automatism and sincerely believed that an exterior force was responsible for their words and deeds. Lacan used this experience to educate himself for the thesis he wrote for his doctorate in 1932, which made an explicit link between psychoanalysis and psychiatry. Lacan felt that he was restoring the traditions of Freud by blending clinical and theoretical work.

Until 1936, Lacan had published only case studies. In that year, however, he wrote several pieces on what he called the Mirror Stage. This centered on the fact that a baby is able to show recognition of its own mirror image before developing many other basic skills, such as speech.

He pointed out that the child must simultaneously understand its mirror image to be both itself and not itself – since, while the image was only a reflection, it was nevertheless a reflection of its true face. Coming to terms with the difference between the two was crucial, Lacan believed, to the development of the child into a social being. This was important because it moved away from the older idea that biological growth was the crucial factor.

The Rome Lecture

In 1953, Lacan presented a lecture in Italy which is usually known as The Discourse of Rome. In the same year, Lacan left the International Psychoanalytical Association after arguing with its focus on the healing of the ego.

In 1953, Lacan presented a lecture in Italy which is usually known as The Discourse of Rome. In the same year, Lacan left the International Psychoanalytical Association after arguing with its focus on the healing of the ego.

Lacan’s position was that this was impossible, and that the goal of psychoanalysis was simply analysis rather than cure. His new body, the Société française de psychanalytique, took his Rome lecture as its founding document. He gave seminars on a weekly basis at a local church, and these began to attract some of the greatest thinkers of the day, including the likes of Levi-Strauss, Foucault, and Barthes. Lacan’s most famous work, Écrits, was based on these seminars.

Other Work and Research

During the next decade, Lacan spent most of his time on structural linguistics, as well as the symbolism in Freud’s own work. Lacan’s view was that Freud had understood the linguistic basis of human psychology, but did not have the requisite linguistic concepts to put it into words.

In one of his seminars, Lacan made the point that there was a linguistic structure to the unconscious, going against the popular view that repressed instinct was its primary governor. Lacan undertook an important translation into French of the works of Heidegger, and was greatly influenced by his ideas on subjectivity, as well as by the work of Hegel.

Lacan Achieves Fame

Lacan’s introduction of structural linguistics into the theory of psychoanalysis brought him wider attention, and by the 1970s he was world famous. His unorthodox ideas and practice included the theory that the subject could be divided into symbolic, imaginary, and real orders, and that language itself could be placed in the symbolic category.

In the later 1960s and early 1970s, Lacan had moved further away from traditional Freudian ideas, developing a specifically Lacanian view that relied on detailed diagrams and newly-coined terms. He was the first to state that the seat of neurosis was the ego itself, and though he claimed that he was following in Freud’s footsteps, this caused considerable argument.

Later Life and Death

Disagreement grew between Lacan and the SFP, and he left to set up the École Freudienne de Paris. The new school’s methods of training were novel, increasing still further the tensions between Lacan and the traditionalists. This was not helped in 1974, when he was named scientific director at the Vincennes site of the University of Paris.

Lacan hoped that the department of psychoanalysis he headed would be able to bring together mathematics, logic, psychoanalysis, and linguistics. By this time, however, even his own followers were showing disquiet at the apparent lack of relevance to clinical psychoanalysis. Lacan set up yet another association, but died in Paris on September 9, 1981.