| Hannibal | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Carthaginian General | |

| Born | 247 B.C. |

| Died | 183/182 B.C. |

| Nationality | Carthaginian |

Hannibal (247-183/182 B.C.) was a Carthaginian general, acknowledged as one of the finest military leaders in history. He spent his life fighting for Carthage against the increasingly powerful Roman Republic, which was seeking to establish its own hold over the Mediterranean. Despite his many achievements, he is best remembered today for his march over the Alps in the dead of winter, accompanied by a troop of elephants, in order to launch an attack on Rome at the start of the Second Punic War.

Early Life

Hannibal’s father was Hamilcar Barca, himself a general of considerable fame. Although Hannibal was born into a family with far-reaching connections: one of his brothers in law was Naravas, the king of Numidia. Nevertheless, it was Hamilcar who had the most influence on the young Hannibal, having vowed to gain revenge for the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War of a few years earlier. Hannibal, inspired by the example of his father, began to accompany him on his military campaigns when he was aged just nine.

Thus, Hannibal’s first experience of battle came during Hamilcar’s expedition to conquer Spain. He was shocked to realize that the Carthaginians had fallen so low since their defeat that they could not travel by sea – the navy was simply not in a sufficiently good state of repair to allow this. Instead, the troops had to be taken by Hamilcar by land to Gibraltar, so that they could be transported quickly across the narrow straits, which were known in ancient times as the Pillars of Hercules, to land in what is now Morocco.

Thus, Hannibal’s first experience of battle came during Hamilcar’s expedition to conquer Spain. He was shocked to realize that the Carthaginians had fallen so low since their defeat that they could not travel by sea – the navy was simply not in a sufficiently good state of repair to allow this. Instead, the troops had to be taken by Hamilcar by land to Gibraltar, so that they could be transported quickly across the narrow straits, which were known in ancient times as the Pillars of Hercules, to land in what is now Morocco.

Early Military Leadership

In his late teens, Hannibal served as a leader of part of Hamilcar’s attacking army, taking his direct orders from Hasdrubal, another of his brothers-in-law. His task was to bring Spain under Carthaginian control, and then to consolidate the power of Carthage in the region in order to prevent any potential rebellion from breaking out. Hasdrubal died in 221 B.C., and at this point Hannibal was chosen as the new commander-in-chief of the Carthaginian forces. He made an immediate impression in his new role, winning large tracts of territory for his country.

A key point in Hannibal’s development came in 218 B.C., when he first experienced a significant clash with the armies of Rome. This came during the conquest of Saguntum, which the Romans saw as a breach the terms of a pre-existing treaty which had been agreed between Carthage and Rome. The Romans delivered an ultimatum to Hannibal: either he surrender his forces to them, or there would be war. Hannibal refused to yield, and the Romans carried out their threat. This saw the outbreak of the Second Punic War.

A key point in Hannibal’s development came in 218 B.C., when he first experienced a significant clash with the armies of Rome. This came during the conquest of Saguntum, which the Romans saw as a breach the terms of a pre-existing treaty which had been agreed between Carthage and Rome. The Romans delivered an ultimatum to Hannibal: either he surrender his forces to them, or there would be war. Hannibal refused to yield, and the Romans carried out their threat. This saw the outbreak of the Second Punic War.

Hannibal and the Elephants

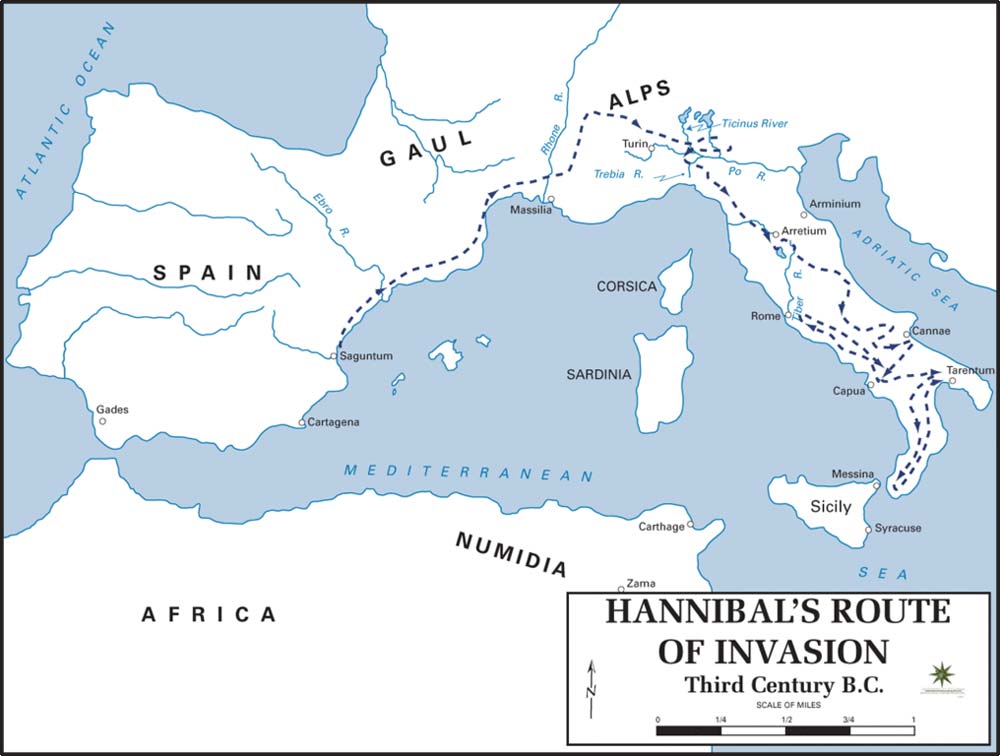

Later in the year 218 B.C., Hannibal began the march that would make him famous, and which would later be recognized as one of the most audacious military assaults in history. Starting out from the Spanish city of Cartagena, or New Carthage, he took his forces over the Pyrenees without significant incident. He then led his armies across the Alps, something which the Romans believed was impossible in the severe winter weather that affected the mountain passes, some of them up to 6,000 feet high.

It is not known for certain where Hannibal made his Alpine crossing, but it is likely that it was in the region of what is today known as the Mount Geveva Pass. Whatever the case, the passes he used were narrow and awkward, and presented considerable dangers to Hannibal’s men – and their elephants. The weather was often against the Carthaginians, with frequent blizzards and gales as well as sudden landslides. On top of this, the tribes who inhabited the mountain passes were generally hostile, and sometimes launched attacks on Hannibal’s men.

It is not known for certain where Hannibal made his Alpine crossing, but it is likely that it was in the region of what is today known as the Mount Geveva Pass. Whatever the case, the passes he used were narrow and awkward, and presented considerable dangers to Hannibal’s men – and their elephants. The weather was often against the Carthaginians, with frequent blizzards and gales as well as sudden landslides. On top of this, the tribes who inhabited the mountain passes were generally hostile, and sometimes launched attacks on Hannibal’s men.

Campaigns in Italy

Most authorities consider that the total death toll during Hannibal’s campaign was in the region of 15,000. Nevertheless, his skill as a leader allowed him to keep both loyalty and morale intact, and his soldiers made short work of the suppression of a number of peoples in the north of Italy. These included the Celtic tribes who inhabited the areas around the River Po, the Ligurians, and the Taurini. At the end of 218 B.C., Hannibal won victories at Ticinus and Trebia, then followed this up with a triumph at the Trasimene Lake the following year.

By now, it was clear to Hannibal that the Roman defenses were not as strong as had been made out and, now knowing of the Roman army’s inadequacy, he launched an invasion of Roman territory itself. This did not amount to a full-scale assault on Rome, however – indeed, he never penetrated within 100 miles of the capital. Instead, he made a temporary settlement for his armies in Campania, considering his next move and allowing his men to recover from their wounds.

The Height of the War

When fighting resumed, Hannibal’s first major opponent was Quintus Fabius. This Roman general generally preferred to stay back from decisive battles, but nevertheless he achieved his most important task: to hold Hannibal back from getting close to Rome itself. This bought the Romans time to rebuild their military capabilities, something which Hannibal knew full well would make his own task that much harder. Partly as a consequence of this, the high levels of morale which the Carthaginians had enjoyed up until now began to come under a certain amount of strain.

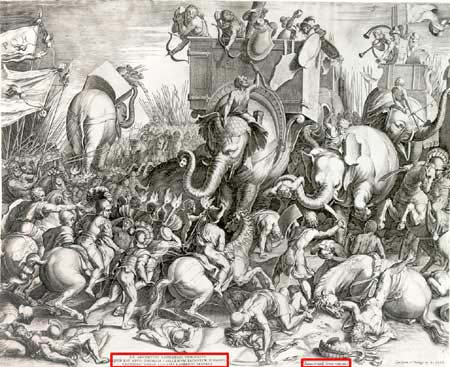

At some point during the year 216 B.C., Hannibal moved his soldiers to Cannae, about 250 miles to the east of Rome. It was from this base that he won the Battle of Cannae. Here, the Carthaginians were faced by a Roman army that was considerably superior in terms of strength, and which had massed its infantry in great numbers. Hannibal responded to this by using a double-envelopment tactic to which his opponents had no answer. The Roman army was annihilated, losing more men than at any other battle other than the Battle of Arausioa hundred years later. Hannibal’s victory at Cannae is considered one of the greatest feats of battle tactics in history.

Decline and Death

Cannae was the high water mark of Carthaginian success in the Second Punic War. A number of city-states in Italy changed sides to support Carthage after the battle, and in 211 B.C. Hannibal at last launched a direct assault on Rome. This was to prove his first major military defeat and, seeing that the great general was not infallible after all, many of his new allies switched back to siding with Rome. Four years later, with Hannibal still stuck, Hasdrubal attempted to bring a force to bolster him, but the Roman army prevented him from reaching his brother.

Hannibal was called back to Carthage in 203 B.C., by which time the tide of battle had turned decisively. By now the Carthaginians were fighting a defensive war, and the Battle of Zama the following year was to prove the beginning of the end. Hannibal was forced to sue for peace in 201 B.C., and he became Carthage’s chief magistrate, hoping to build the city back up to a point where war would once again be a realistic possibility. The Romans, realizing this, dismissed him, and he fled first to Crete and then Bithynia. In either 183 or 182 B.C., again under attack from a superior Roman army, Hannibal refused to surrender, instead committing suicide by drinking poison.