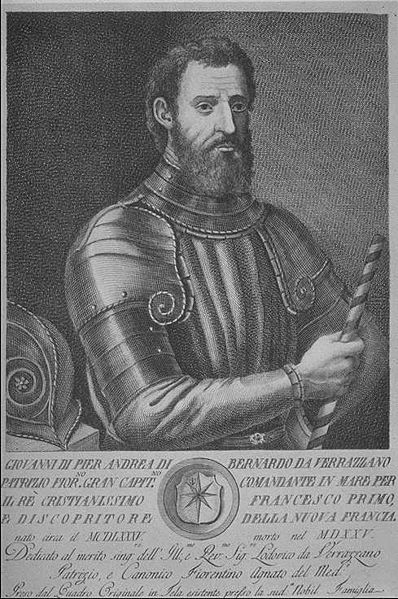

Born in Italy in the year 1485, Giovanni da Verrazzano explored the continent of North America extensively during his life, but in the name of France, not Italy. Much of his fame came from his explorations of North America’s Atlantic coast from the Carolinas up to Newfoundland, and he was the first to do so after Norse expeditions around the turn of the first millennium. He has been honored in the States with having his name applied to bridges, ships, and places.

Born in Italy in the year 1485, Giovanni da Verrazzano explored the continent of North America extensively during his life, but in the name of France, not Italy. Much of his fame came from his explorations of North America’s Atlantic coast from the Carolinas up to Newfoundland, and he was the first to do so after Norse expeditions around the turn of the first millennium. He has been honored in the States with having his name applied to bridges, ships, and places.

Life and First American Expedition

Born in the south of Florence in Italy to Piero Andrea di Bernardo da Verrazzano and Fiametta Capelli, Giovanni da Verrazzano’s exact date of birth is unknown, and there have been alternative birthplaces proposed. Because he served the king of France, French scholars have purported him to be of French birth, but that theory has been mostly discredited. He always referred to himself as a native of Florence and was called a Florentine by contemporaries.

While Verrazzano wrote lengthy and detailed reports about his voyages and explorations of the Americas, we know very little about the details of his personal life. What can be verified is that he came to live in France at the Port of Dieppe sometime after 1506. It was there that he became a seafarer and a navigator, and learned his first lessons in sailing a ship. Sometime around 1508, he left France on his first trip to the Americas on the ship La Pensee, owned by Jean Ango, and captained by Thomas Aubert. Upon his arrival he took a small fishing craft from the La Pensee and made his first solo explorations of areas of Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence river, now in Canada. He returned to France and added to his experience as a seaman by traveling to the Mediterranean and back.

The Second American Journey

In 1523 King Francis I of France enlisted Verrazzano to explore the coast of the new world from Newfoundland to Florida for the purpose of finding a route via ship to the Pacific Ocean. Recent events had convinced the French monarch that new routes for trade must be opened. There was stiff competition with French merchants and bankers from Portugal for existing trade, and Magellan’s travels around the world had shown that alternate routes existed.

In 1523 King Francis I of France enlisted Verrazzano to explore the coast of the new world from Newfoundland to Florida for the purpose of finding a route via ship to the Pacific Ocean. Recent events had convinced the French monarch that new routes for trade must be opened. There was stiff competition with French merchants and bankers from Portugal for existing trade, and Magellan’s travels around the world had shown that alternate routes existed.

After agreeing to head the expedition for the French king, Verrazzano left with four ships, intending to cross the Atlantic straight west and arrive at the Grand Banks area of Newfoundland. After two of the ships were lost to storms and perilous seas, the remaining two ships returned, barely seaworthy and in need of repair as a result of the adventure to Brittany. By the end of 1523 the ships had undergone repair and refurbishment and were ready to try the voyage a second time. Perhaps in an attempt to avoid the stormy seas of the first trip, the ships headed south through a calmer but more dangerous ocean – dangerous because the area was under the control of Portuguese and Spanish forces.

Verrazzano’s ship, called La Dauphine, was the only one to make it out of the hazardous seas and across the Atlantic, arriving near Cape Fear in March of 1524. Further travels brought the ship to the present Pamlico Sound area of North Carolina, where Verrazzano wrote that he firmly believed the Pamlico Sound was the entrance to a passage to the Pacific, and from there, a route to China could easily be found. This erroneous information caused incorrect and inaccurate maps of the coastline to be made, and it would remain incorrectly charted for future explorers for years to come.

Heading north up the coast of the Carolinas, Verrazzano and his men encountered several coastal tribes of Native Americans, but he failed to take note of the Chesapeake Bay or Delaware River entrances into the continent, both of which might have been surmised to be routes west. Upon arriving at New York Bay, he wrote that he and his men had found a large lake, when it was actually the Hudson River’s mouth. Proceeding parallel to Long Island, the expedition arrived at Narragansett Bay and there it met the Wampanoag tribe’s delegation. The site of this meeting was named Norman Villa by Verrazzano to honor a nobleman in France, whose name was used on maps of the area drawn up in 1527. Similarly, an area west of this in present-day Delaware or New Jersey was called Longa Villa by Verrazzano, again to honor a French nobleman.

After a stay of about two weeks at this location, Verrazzano took his crew and La Dauphine north. They explored the coastal stretches of what is now Maine, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland, and narratives of these adventures were written by the captain for posterity. Information gained on this leg of the journey was also used to make maps of the American coastline. Maps named the region he had explored Nova Gallia, which means New France, but according to his diaries, Verrazzano originally wanted it to be called Francesca. The successful second American trip ended with a return to France in July of 1524.

Last Voyages and Death

After this voyage, Verrazzano remained in his French home, inactive for a few years but writing his memoirs. When two noble financiers approached him with a plan to return to America to look for the so far unfound route to the Orient, he assented at once. This time he was in charge of a small fleet of four ships and the expedition sailed from the Port of Dieppe in early 1527. After a storm in the area of the Cape Verde islands separated one ship from the group, he arrived at the Brazilian coast with two ships, with the third trailing behind. Verrazzano was able to fill the holds of the ships with the brazilwood which they harvested, and left enough for the third ship as well. He returned from Brazil with the precious cargo and arrived in Dieppe in the fall, with the third brazilwood-laden ship following close behind.

While the explorer had been successful in returning with a valuable cargo, he had not been able to find the much sought after passage to the Pacific and points beyond, and a subsequent voyage to the new world was soon planned and executed. In the early months of 1528, Verrazzano left Dieppe for the last time in his sea-going career. He was able to make valuable contributions to knowledge of the area while exploring present day Florida, the Bahamas, and the Lesser Antilles. At a stop believed by historians to be near the island of Guadeloupe, Verrazzano was anchored at sea with his ships when he decided to take a small boat and row to shore by himself. There he fell victim to native cannibals and died, presumably providing dinner in the process. The year was 1528.

Legacy

Some controversy among historians surrounded the veracity of Verrazzano’s writings for many years, even into in the 20th century. These letters and reports were finally accepted as true, and his place in the history of the exploration of America was firmly established. The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge was named after the explorer, as was a ferryboat serving the New York to Staten Island run. Bridges in the Narragansett Bay area bear his name, as do innumerable community memorials and organizations. He is a source of pride to the Italian-American community, and an important part of the early history of the exploration of what would come to be known as America.