| First Battle of Bull Run | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Military Leaders | |||||||

| Irvin McDowell | Joseph E. Johnston | ||||||

| P.G.T. Beauregard | |||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| 28,000–35,000 (18,000 combated) | 32,000–34,000 (18,000 combated) | ||||||

| Casualties and Deaths | |||||||

| Total: 2,896 | Total: 1,982 | ||||||

| 460 killed 124 wounded 1,312 captured/missing |

387 killed 1,582 wounded 13 missing |

||||||

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

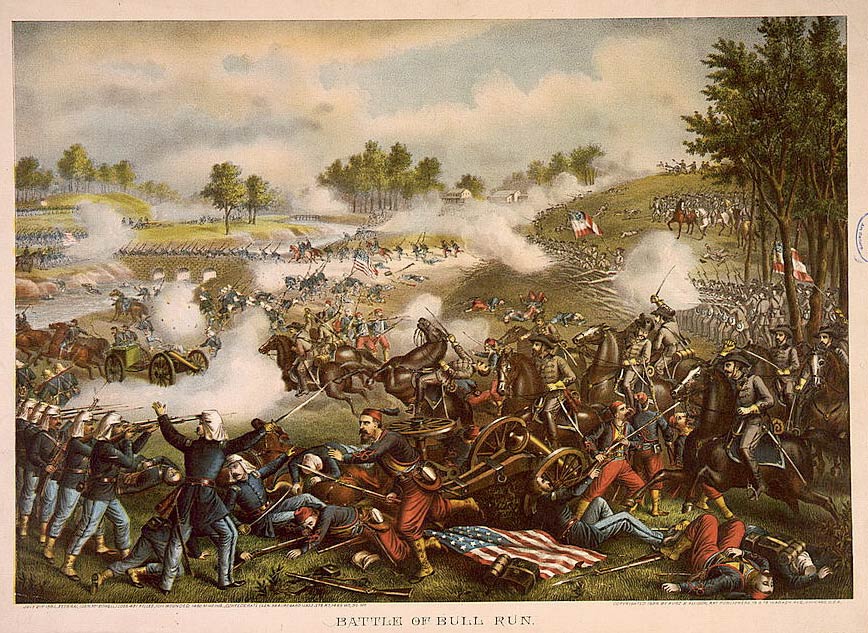

The first big land battle of the American Civil War took place near Manassas in Prince William County in Virginia on July 21, 1861. This episode is called the First Battle of Bull Run and is also known as First Manassas, the latter being the name the Confederates used.

The battle came about as a result of a Union drive to try and take Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederate states, as it was felt that taking the city would mean an early end to the uprising.

Brigadier General Irvin McDowell was in command of the Union army, while Confederate forces were led by Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard. Soldiers on both sides were green recruits, and the lack of experience and discipline resulted in the Union army’s failure in its attempt to outflank the Confederates at Bull Run.

Despite the failure of the maneuver, the Union army initially held the advantage. Union progress was stalled by stern resistance from a brigade of Virginian soldiers led by Colonel Thomas J. Jackson. It was this incident that led to the colonel getting the nickname “Stonewall” Jackson. The Federal numerical supremacy in the battle changed with the arrival by train of Confederate reinforcements under the command of Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston.

Boosted by the additional troops, the Confederates launched a vigorous counterattack, forcing the Union army to begin a retreat that soon turned into disorganized panic. The battle soon turned into a Confederate rout.

The first major conflict of the Civil War shocked many people on both sides. The First Battle of Bull Run was significant for the ferocity of its fighting, and the high casualty rate. It was the first indication that the Civil War would be a long and brutal affair.

Background

Brigadier General Irvin McDowell had been appointed as commander of the Army of Northeastern Virginia by the President, Abraham Lincoln. He immediately came under pressure to launch a decisive military operation against the Confederates in Richmond, but argued strongly against this option. McDowell was concerned by the lack of experience of his troops, and felt that such a major undertaking was beyond their capabilities.

McDowell eventually bowed to the pressure, including that from the President himself, and assembled his forces at Washington. Standing at 35,000 men, this was the largest army that had ever assembled in America, and it left Washington on July 16th.

Battle Plan

General McDowell planned to launch two separate attacks on the Confederate forces, and split his forces into three columns. Two of these columns were to attack the Confederates at Bull Run, and it was intended that the third column was to outflank the enemy forces and attack from the rear. This maneuver would also give the Union forces control of the railway line from Richmond.

McDowell knew his army outnumbered the Confederates, who had just under 22,000 troops at Bull Run, and he felt sure that once the attack on Bull Run was initiated, the rebels would withdraw back to the Rappahannock River. He was even confident enough to dispatch 5,000 soldiers to provide rearguard protection to his forces.

He had previously dispatched a brigade of some 18,000 men under the command of Major General Robert Patterson to tackle the Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley so that they could be used as reinforcements in the battle at Bull Run.

On July 18th, McDowell dispatched a division under the command of Brigadier General Daniel Tyler to pass the Confederate forces on their right flank. This maneuver failed when Tyler and his men were met with Confederate resistance at Blackburn’s Ford and were unable to continue forward.

Overall, McDowell’s plan failed for several reasons. Dividing his forces into three columns was not viable because of poor coordination and communication within the unskilled ranks. Secondly, Major General Robert Patterson had failed in his attempt at the Shenandoah Valley and the Confederates had managed to bring the reinforcements in. This meant that when the battle began, the Union army no longer outnumbered the Confederates to such a great extent.

The Battle

On July 21st, McDowell dispatched 12,000 troops along the Warrenton Turnpike to march to Sudley Springs, while Tyler was ordered to take his troops to the Stone Bridge. These soldiers were sent out at 2:30 am, the intention being to catch the Confederates by surprise at first light.

On July 21st, McDowell dispatched 12,000 troops along the Warrenton Turnpike to march to Sudley Springs, while Tyler was ordered to take his troops to the Stone Bridge. These soldiers were sent out at 2:30 am, the intention being to catch the Confederates by surprise at first light.

From the very start, things went wrong, with Tyler’s division blocking the turnpike and preventing the main force from advancing. The Union leader had also failed to realize the roads into Sudley Springs were often little more than dirt tracks. As a result, the army did not reach the Bull Run River until 9:30 am.

Even though the Confederates, under the command of Colonel Nathan Evans, were hopelessly outnumbered by almost twenty to one by the oncoming Union army on the left flank, the Union army seemed to be launching half-hearted attacks. This led Colonel Jones to suspect that these attacks were diversionary, and when he learned of the movement of Union troops towards Sudley Springs, he immediately moved his men to Matthew’s Hill, where he soon received reinforcements, and these men succeeded in delaying the Union army from crossing Bull Run.

Eventually, the Confederates were forced to retreat from Matthew’s Hill, having suffered a surprise attack from the flank by Tyler’s men. However, McDowell failed to press home his advantage, and instead of commanding his forces to take conceded ground, he instead ordered artillery bombardment of the enemy locations. This delay allowed the confederate forces to reassemble.

Final Phase

The Confederates also brought their artillery weapons into the battle, and the next phase was a straight fight between the heavy guns of both sides. Confederate guns were better suited to the conditions, and eventually the Confederate action was successful and the Union guns were taken.

This was the end for the Union forces. By 4 pm, McDowell had ordered his forces to withdraw. The withdrawal soon descended into chaos and panic, as the retreating soldiers were bombarded by Confederate artillery.

Casualties on both sides were significant. 847 men were killed, and 2706 were wounded. A further 1,325 soldiers, mainly from the Union army, were captured or missing in action.