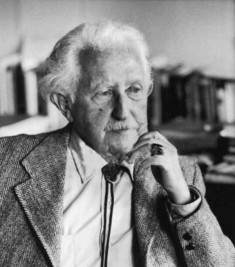

| Erik Erikson | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Psychologist | |

| Born | 15 June 1902 Frankfurt am Main, Germany |

| Died | 12 May 1994 (aged 91) Harwich, Cape Cod, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | German-American |

Erik Erikson was a German-American psychoanalyst and psychologist. He is most famous for his theories of human psychosocial development and for being the originator of the term “identity crisis.”

Erikson reached professorial status at Harvard and several other well-known academic institutions despite his lack of an advanced college degree of his own. He was the author of the classic 1950 publication, Childhood and Society, as well as several other books. He was significantly influenced by Sigmund Freud.

Early Years

Erikson was born on June 15, 1902, in Frankfurt, Germany. He was the product of an extramarital romance between his mother and an unidentified Danish man. His mother was widowed shortly afterward, and remarried in 1905; her new husband was Theodor Homburger, a pediatrician who adopted the boy six years later.

As Erikson grew up, he came to realize that he was not his father’s blood relation, and for that reason he took on the role of an outsider. This was exacerbated by his Jewish heritage, which caused him some awkwardness at school. At his synagogue, conversely, his tall, blonde looks also attracted some teasing.

Educational Years

His stepfather wanted Erikson to enroll in medical school, but the boy wanted to study art. When his stepfather refused to support the idea, Erikson left home to begin a course at Baden State Art School, followed by time spent traveling in Europe.

He earned money by painting portraits of children in Vienna, which brought him into contact with Anna Freud at an art school run on psychoanalytical lines. Freud quickly realized how good Erikson was with children, and became his mentor. This brought him both the approval of the Psychoanalytic Society of Vienna and a degree in teaching, specializing in the Montessori Method.

Moving to America

Erikson and his wife, Joan, became alarmed at the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, and decided to emigrate. After a short spell in Denmark, they settled in the United States. Erikson, lacking an advanced degree, was stopped from working as a child psychoanalyst and instead worked as an assistant at both Yale and Harvard Universities.

In the end, his links with the society in Vienna were what allowed him to set out on the professional course he really wanted. Moving to San Francisco, he was employed by the University of California at Berkeley as a lecturer and research associate. By 1950, he was an accepted and respected member of the psychoanalytical elite in the area.

Erikson’s Career Begins to Flourish

From 1939, he had been an American citizen and he now began his most important work, studying how the Yurok and Lakota Native American tribes operated with regard to rearing their children. He drew on the knowledge of Franz Boas, Margaret Mead, and other cultural anthropologists, blending them with Sigmund Freud’s theories to create a distinctive stand of his own.

From 1939, he had been an American citizen and he now began his most important work, studying how the Yurok and Lakota Native American tribes operated with regard to rearing their children. He drew on the knowledge of Franz Boas, Margaret Mead, and other cultural anthropologists, blending them with Sigmund Freud’s theories to create a distinctive stand of his own.

Although he followed Freud in matters such as the existence of the Oedipus Complex and the nature of the ego, he also brought in anthropological concepts of culture and society. Erikson felt that the different guidance, cultures, and nurturing styles of each society were crucial in determining a child’s psychological development.

Major Contributions to Psychology

Erikson was able to reconcile these differences and formulate a universal developmental theory, based on eight phases centering on concepts such as trust, autonomy, shame, and initiative. With the first, for example, a child had to discover how to trust others while avoiding going so far as to tip over into being gullible.

These eight stages covered only a child’s first five years, after which Erikson believed that personality was fully formed. Nevertheless, he appreciated that development as a whole lasted a lifetime, given the inevitable existence of life crises. He believed that those who had not been able to resolve their childhood phases satisfactorily would always have trouble dealing with crises in adulthood.

Personal Life and Death

Erikson himself had a son who had Down Syndrome and was institutionalized for the entire 21 years of his life. Doctors had expected him to live no more than three years, and his parents accepted the doctor’s suggestion that he be transferred, telling his siblings that he had died.

When the truth emerged, there was considerable unhappiness in the Erikson household. This was the time at which Childhood and Society was published, but Erikson stepped down from his Berkeley position to avoid persecution by McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1960, he went to Harvard as a professor, spending the rest of his life writing extensively: he won a Pulitzer Prize for his work on Gandhi. Soon after being diagnosed with prostate cancer, he died in Massachusetts on May 12, 1994.