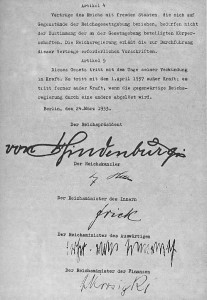

The Enabling Act of 1933 was an amendment to the German constitution. It is generally seen as the point in which Adolf Hitler began his transformation from a democratic chancellor to a dictator. Signed into law on March 23, 1933, it followed the Reichstag’s Fire Decree and allowed Hitler to implement laws without the consent of the Reichstag. The act’s effects would last for a period of four years, but it could be renewed by the Reichstag for additional four-year terms.

Background

Hitler, having been appointed German chancellor in January of 1933, requested that President Paul von Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag. Six days before this, the Reichstag fire occurred, with the Nazis painting it as an incipient communist revolt. The resulting Reichstag Fire Decree suspended a number of civil rights, including that of habeas corpus. The Communist Party’s headquarters were raided on Hitler’s orders, followed by the arrest of some of its representatives.

The Nazis achieved much more success than in previous years, but they still failed to win an overall parliamentary majority and needed support from the German National People’s Party. Hitler, hoping to circumvent this difficulty, began working on the Enabling Act. The act would allow the cabinet—or Hitler himself—to submit legislature over the heads of the Reichstag, thus allowing the Nazis complete authoritative power despite their lack of majority.

Preparing the Act

Since the Enabling Act would allow laws to be passed that went against the constitution as it stood at the time, the act itself counted as a constitutional amendment. Because of this, it would require two-thirds of Reichstag members to vote in its favor, as well as a quorum of two-thirds of deputies to be in attendance. Both the Communists and the Social Democrats were widely expected to vote against it, despite the arrest of many of their members under the Fire Decree. Middle-class parties were seen by the Nazis as likely supporters, since they had become disillusioned with the republic’s stability.

Since the Enabling Act would allow laws to be passed that went against the constitution as it stood at the time, the act itself counted as a constitutional amendment. Because of this, it would require two-thirds of Reichstag members to vote in its favor, as well as a quorum of two-thirds of deputies to be in attendance. Both the Communists and the Social Democrats were widely expected to vote against it, despite the arrest of many of their members under the Fire Decree. Middle-class parties were seen by the Nazis as likely supporters, since they had become disillusioned with the republic’s stability.

Therefore, support of the Center Party was the key requirement for Hitler. He concluded talks with the Center Party on March 22, and gained their support for the act in exchange for assurances concerning freedom for Christians. Some authorities believe that Hitler also promised to sign a contract with the Vatican, giving the Catholic Church a specific national role in Germany for the first time. Shortly after the vote on the Enabling Act, the leader of the Center Party traveled to Rome to see whether such an agreement was possible, though no decisive evidence has been found.

The Act Becomes Law

Disagreement persisted within Center Party ranks about whether to support the act right up until the vote itself on March 23rd. Eventually it was agreed that solidarity within the party was crucial, and the Center Party gave its approval as a whole. The Social Democrats hoped to prevent the passing of the bill by boycotting the session, therefore depriving the Reichstag of the mandatory two-thirds attendance required for passing an amendment. However, the Center Party counteracted this plan by altering the Reichstag’s procedural rules to count members who were away “without excuse” as present.

Disagreement persisted within Center Party ranks about whether to support the act right up until the vote itself on March 23rd. Eventually it was agreed that solidarity within the party was crucial, and the Center Party gave its approval as a whole. The Social Democrats hoped to prevent the passing of the bill by boycotting the session, therefore depriving the Reichstag of the mandatory two-thirds attendance required for passing an amendment. However, the Center Party counteracted this plan by altering the Reichstag’s procedural rules to count members who were away “without excuse” as present.

The Social Democrats therefore attended the Reichstag assembly, where a number of SA members were in attendance. Hitler gave a speech, aimed primarily at the Center Party whose support he so badly needed, emphasizing the central role of Christianity in German culture. The party’s leader, Ludwig Kaas, then spoke, giving the party’s support for the proposed legal changes. In contrast, Otto Wels, who chaired the Social Democrats, spoke out against the act, attacking it for crushing “eternal” ideas of democracy and freedom.

Thanks in part to intimidation from the SA men at the session, only the Social Democrats voted against the Enabling Act. The final tally in the vote was 444 deputies in favor to 94 against. The 83% majority was more than sufficient to clear the constitutional hurdles, and it was signed into law soon after.

Effects of the Act

Once the Enabling Act had passed into law, Hitler could pass laws without parliamentary approval, even if they went against the German constitution. Although the Reichstag and the presidency were initially protected, both these offices were removed in 1934. The combination of the Enabling Act and the Reichstag Fire Decree effectively made the Nazi government a dictatorship.

New laws and legislature continued to be placed before the Reichstag for informational purposes, but the committee set up to do this work had no real impact and was quickly abandoned. While, in theory, the act’s legislative powers had been granted to the German cabinet as a whole, in reality Hitler possessed the power himself. After 1938, the cabinet ceased entirely to meet.

Hitler Takes Control

Without the power to halt new laws, the Reichstag became little more than a place for Hitler to give speeches, and it continued to meet occasionally until the end of WWII in 1945. In any case, by July of 1933 the Nazi Party was the only remaining legal party in Germany. Hitler was still anxious to give the appearance of acting within the law, and both 1937 and 1941 saw the act formally renewed. By 1942, however, a law had been passed which effectively extended the Enabling Act’s provisions until the end of the war.

Despite the Enabling Act’s sweeping provisions, Hitler exceeded even the powers it granted him on two separate occasions. The first was the abolition of the Reichstag in February of 1934, which was carried out despite the act making specific provision for its existence. Similarly, the death of President Hindenburg a few months later allowed Hitler to take presidential powers for himself as well, despite the Enabling Act protecting the office of the president from interference.