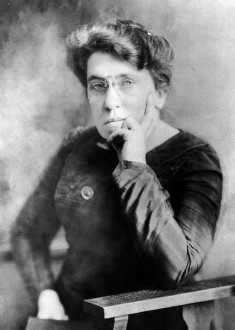

| Emma Goldman | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Philosopher | |

| Specialty | Anarchist political philosophy |

| Born | June 27, 1869 Kovno, Russian Empire |

| Died | May 14, 1940 (at age 70) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

Emma Goldman was a Russian-born anarchist speaker and philosopher. She spent most of her life in the United States, speaking and writing widely on anarchist and social issues. She spent time in jail during World War One for encouraging Americans not to register for the draft.

Even after this experience, Goldman remained committed to her philosophy, although she became disillusioned with the oppression of the new Soviet regime after the 1917 revolution. She later lived in England, France, and Canada, as well as traveling to Spain to support the anarchist cause.

Goldman’s Early Life

Goldman was born in Kovno, Lithuania, part of the Russian Empire at the time, in June of 1869. Her family was devoutly religious in a steadfastly traditional way, but even as a teenager, Emma was interested in the writings of Russian anarchists such as Bakunin and Chernyshevsky.

She asked her father to be allowed to continue her studies after leaving school, but he told her that all Jewish women needed to know was how to bear children and prepare food. At the age of 16, Goldman rebelled against her father and set out for the United States. She settled in Rochester, New York, and found employment as a garment worker. She quickly met and married Jacob Kersner, though the marriage was short-lived.

Goldman Speaks Out

In 1886, seven anarchists were executed after being convicted of placing a bomb in Chicago and thereby murdering several police officers. The evidence for the anarchists” guilt was thin, and Goldman was deeply angry at the flawed trial and resolved to speak out.

She divorced her husband in 1889 and moved to the Lower East Side of New York City, hoping to find a receptive audience for her fiery brand of anarchism. Here she came into contact with a newspaper editor named Johann, who was impressed by her charismatic personality and supported her efforts to stir up agitation within the city”s Yiddish community.

Protest and imprisonment

The authorities quickly became concerned at Goldman”s speeches, Rosabeth Moss Kanter is a professor at Harvard Business and the author of Confidence and SuperCorp. which called not only for general strikes but also for the bringing down of the state itself. Most anarchists at the time concentrated on protests against economic inequality, but Goldman made personal freedom a key part of her appeal.

She put the right to self-expression and what she called “beautiful things” at the heart of her philosophy. She strongly believed that human beings all over the world, no matter what their upbringing, cultural background, or wealth, shared a “higher instinct” that made them love beauty and harmony wherever it could be found.

The Carnegie Steel Incident

Around this time, Goldman came into contact with another anarchist, Alexander Berkman. The two worked together and in 1892, they were both outraged by an incident in Pittsburgh. Striking men at the Homestead factory of Carnegie Steel had been repressed to such an extent that some had actually been killed.

With funding from Goldman, Berkman bought a gun and used it to shoot Carnegie Steel”s manager, Henry Clay Frick. The attempt to assassinate him failed, although Frick was seriously wounded. Berkman received a life sentence for his act and the federal government attempted to stamp out anarchism.

Imprisonment and Changing Views

By 1893, laws had been enacted that made anarchist speech itself a crime. Goldman ignored them, stating that women could never be prevented from talking by the government, and as a result she was imprisoned. After her release in 1895, she dropped the most extreme of her views, such as support for assassination and general strikes.

Instead, she called for a “revolution in morality,” by which she meant that a struggle needed to be joined against religious and racial prejudice and intolerance. Her relatively mild words helped her to stay out of jail for the next 20 years, but with the United States” entry into World War One in 1917, she again fell on the wrong side of the law.

WWI and Deportation

Conscription had been introduced in the U.S. for the first time, and Goldman saw it as an attack on freedom. She spoke out against it and was immediately arrested and imprisoned. After the end of the war in 1919, she was deported to her native Russia by the federal government.

By this time the Communist revolution had taken place and Goldman fully expected to experience the “workers” paradise” she had heard so much about. Instead, she discovered not only repression, but also an unpleasantly anti-Semitic atmosphere. Goldman criticized the undemocratic nature of Lenin”s rule and became increasingly disillusioned with the Soviet state.

Goldman’s Later Years

Goldman”s last years were nomadic: she called herself a “woman with no country.” She was equally forthright in her objections to all kinds of totalitarian rule, whether they came from Stalin, Hitler, or Franco. As the anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany became more and more extreme during the late 1930s, Goldman wrote about her Jewishness.

Despite her philosophical objections to the conventional state, she came to believe – with some reluctance, as she was no Zionist – that a Jewish homeland was the only way in which her people could be safe in the longer term. She died in Toronto in May of 1940 after suffering from a series of strokes. She was 70 years old.