Dred Scott v. Sandford, otherwise known as the Dred Scott Decision, was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1857 and seen as a landmark decision in the debate surrounding the constitutionality and legality of slavery. The decision of the court was that people who had entered the United States as slaves could not rely on the protection of the United States Constitution. The decision later became considered to be among the worst verdicts ever handed down by the Supreme Court.

Background

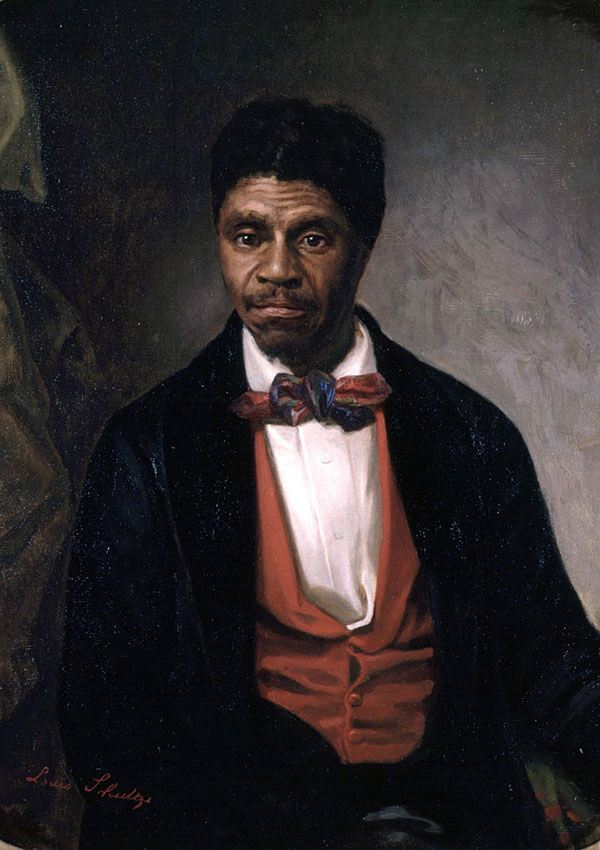

Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia, around 1795; he moved with his owner to Missouri in 1820. Thirteen years later, after his master had died, he was taken by a new owner, Emerson, to Illinois. At the time, this was a free state, and had been since its admission to statehood in 1819. In 1836, Scott was moved to the Wisconsin territory, an area which – under the Missouri Compromise of 1820 – had “forever prohibited” the establishment of slavery and where several recently-passed acts had strengthened this prohibition.

Emerson nevertheless kept Scott as a slave for more than two years, during which time Scott married. Since slaves in the southern states could not enter into a marriage contract, the fact that Scott was able to do this would have underlined the validity of his claim to freedom – but he did not sue. By the end of the 1830s, Emerson had taken Scott, his wife, and their newborn daughter to Louisiana, and it was here – after Emerson had died – that, in 1846, Dred Scott went to court in order to obtain his freedom from Emerson’s widow, Eliza.

Lower Courts

In 1846 when, with the assistance of sympathetic lawyers, Scott brought a lawsuit against Eliza Emerson in Missouri, arguing that he had resided in free territories for an extended period of time, which therefore made his emancipation mandatory. The same argument was made for his wife, while his daughter must have been born free as she had been born on a boat traversing a river between two free lands. Precedent in Missouri suggested that the Scotts would win their case – but it was thrown out because no witness had testified that Scott was indeed Eliza Emerson’s property.

After losing another round of his fight in the Missouri Supreme Court in 1850, with Eliza Emerson’s brother, John Sanford, now advocating. Scott took his case to a federal court in 1853. He did so on the grounds that Sanford now resided in New York and that the diversity jurisdiction of the United States Constitution allowed the case to be heard federally. When this case came to court in 1854, the judge told the jury that the matter of Scott’s free or slave status would have to be decided according to the laws of Missouri, which had already ruled against Scott. He now made an appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

U.S. Supreme Court

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court handed down its verdict: Scott was not entitled to Constitutional protection, as he was not a legal citizen of the United States. Of the nine Justices who sat on the case, six concurred with the full ruling, two dissented, while one agreed with the ruling itself but differed in his reasoning. There were a number of aspects to the Supreme Court’s overall argument in dismissing Scott’s case, several of which were related.

The Justices held that Scott could not legally take his case to a federal court, because the writers of United States Constitution had not intended for black people to be seen as equal to whites. Since Scott was therefore not a U.S. citizen, the court had no jurisdiction over his case. The Court also ruled that, even if Scott had been a full citizen of Missouri, it was impossible for any single state to unilaterally admit a person to citizenship as defined by the Constitution. The Court further held that Missouri’s verdict that Scott was a slave therefore stood.

The Court also decided that Congress had overreached its power in enacting the Missouri Compromise, because its power to do this applied only to the Northwest Territory and not to other areas of the continent, such as Louisiana. This was only the second time that the Court had ever struck down an Act of the U.S. Congress as being unconstitutional.

Dissenting Opinions

Justice Curtis’s dissenting opinion argued that if the Court felt that it did not have jurisdiction over a case, its task was simply to dismiss it, rather than making comments about the relative strengths and weaknesses of each party’s claims. Both he and Justice McLean, who also dissented, objected to the striking down of the Missouri Compromise, saying that was an unnecessary part of the decision. Further, McLean pointed out that at the time the U.S. Constitution had been signed, five out of the 13 states then in existence had granted the vote to black men, and that they were indeed therefore U.S. citizens.

Political Influence

Before the opening of the U.S. Supreme Court case, James Buchanan, who had been elected but not yet inaugurated as President of the United States, wrote to John Catron, Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He expressed a desire both for the case to be decided before March 1857, when Buchanan was due to be inaugurated, and for a verdict that would place the debate on slavery beyond politics and thereby calm popular agitation on the subject. Buchanan had gone further and persuaded another Associate Justice – who was from the North – to vote with the Southern majority.

Aftermath

Almost at once, the financial storm known as the Panic of 1857 erupted, as people worried whether the new West would become slave territory. Many saw the Dred v. Scott verdict as being the ultimate expression of what they felt to be the movement to increase the reach of slavery, with many Southerners arguing that the U.S. Constitution allowed them to move slaves with them into the new territories, regardless of what the legislatures of those areas had previously ruled.

Northern abolitionists became increasingly vocal while Southern supporters of slavery insisted on further concessions. The Democratic Party became driven by dissent and factionalism, while the Republicans grew in strength and influence. By the end of 1858, Abraham Lincoln was openly warning of the threat that the next Supreme Court ruling might require slavery to be permitted across the United States. Arguments grew more and more heated, and the slide towards eventual civil war had begun.

Dred v. Scott itself was never formally overturned by another Supreme Court decision, but it was effectively removed from consideration after the Fourteenth Amendment had been passed, guaranteeing citizenship to everyone born in the United States as well as guaranteeing them protection under the Constitution.