The Compromise of 1850 is the name given to a package of bills passed in September 1850, aimed at defusing a stand-off between the Northern free states and the Southern slave states. The argument concerned those territories which had been acquired by the United States during the Mexican-American War of the late 1840s and, in particular, their status. The compromise was a qualified success in that it averted the immediate threat of war or secession. However, it did not lead to a long-term settlement: the outbreak of the American Civil War was delayed by barely a decade.

Background

In 1850, California was poised to be admitted to the Union as a state, and for that reason, it was imperative that a solution be found to the question of slavery. President Taylor, in name only head of the Whig Party, was weak and lacked effective power, so the party asked Henry Clay to work out a compromise proposal that would be acceptable to each faction in the argument. Thirty years earlier, Clay had been the man behind the Missouri Compromise, and later he had been instrumental in settling the nullification question, so hopes were high that he would achieve another breakthrough.

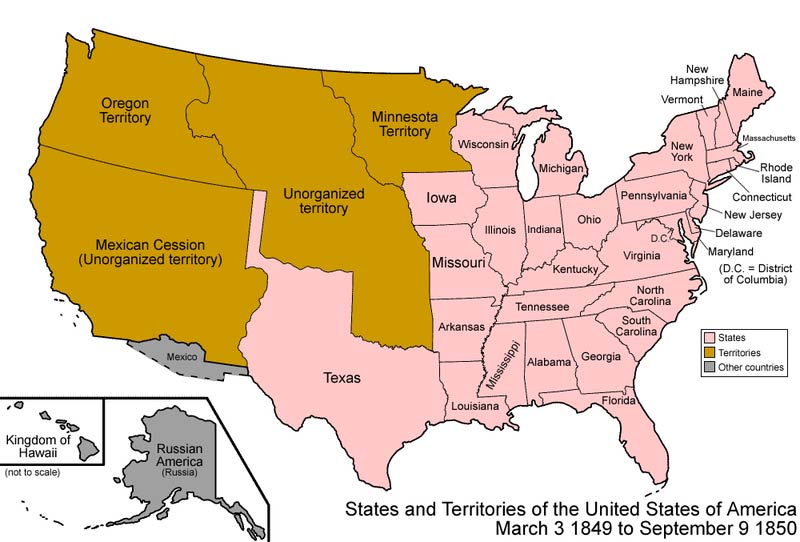

Clay appreciated that the immediate topic of what to do with the land the U.S. had gained from the Mexican Cession was far from being the whole story. Northerners were widely unhappy with the fact that slave markets still existed in Washington, while Southerners felt that the 1793 law which governed the handling of runaway slaves was outdated and inadequate. In January 1850, Clay put together what was called the omnibus bill: a collection of related resolutions, all dealing with the questions at hand.

The bill proposed that California should be a free state on admission to the Union, while Utah and New Mexico would be territories and have the question of slavery within their borders addressed by popular sovereignty. The District of Columbia would end the slave trade – although not the institution itself – and Congress would make a declaration that it had no power to intervene in slave trading between the states. Finally, the New Mexico-Texas border would be determined once and for all, and the U.S. would take on the debt Texas had accumulated before being annexed.

Debate in the Senate

The Senate debated the omnibus bill for six long months, and rumblings grew that Southern states were considering secession. Clay took to the floor of the Senate to defend his proposals, arguing that war would be the inevitable result of secession. Responding, Calhoun argued that the South should have equal rights in the territories, that their right to practice slavery should be respected, and that the Constitution should be amended to return power to the South. This last point was kept vague. Daniel Webster broadly supported Clay’s proposals, but attacked what he saw as extreme elements on both sides of the debate. Among them was Willliam H. Seward, a New York senator, who objected to even the smallest ground being ceded to slavery.

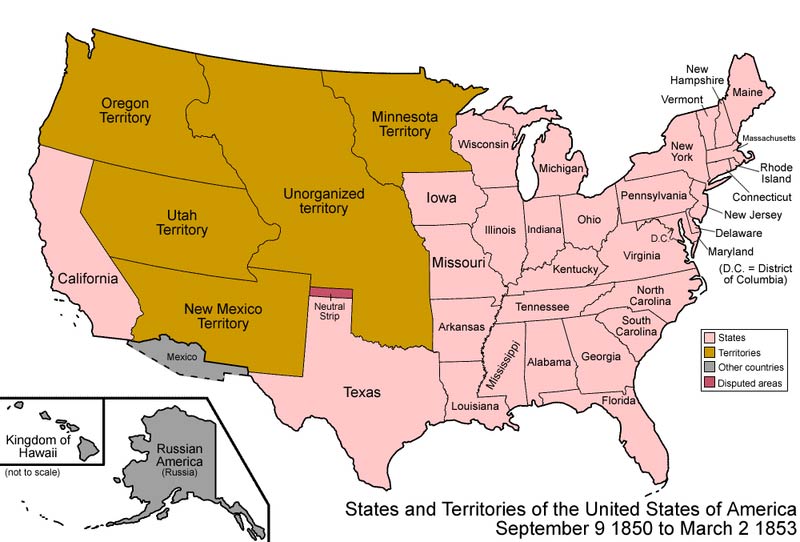

The omnibus bill did not pass, but an Illinois Democratic senator, Stephen Douglas, succeeded in getting the bulk of the proposals passed as five separate bills. The first, and in some respects the least controversial, was the admission of California to the Union as a non-slave state. Second, New Mexico was allowed to become a territory in the manner already outlined, and its border with Texas was firmly demarcated. In exchange for dropping its claims to New Mexican territory, the state of Texas was paid the sum of $10 million by the United States government.

The third bill created the territory of Utah under the same conditions that had been applied to New Mexico. The fourth bill required that the trade in slaves be abolished within the area of the District of Columbia. Commerce in slaves was to be outlawed from the first day of 1851, and a secondary provision required that the District must not be utilized as a slave-shipping point. The final bill amended the Fugitive Slave Act and gave greater rights to the owners of slaves, placing all such cases under the jurisdiction of the federal government. This was the bill which caused the greatest controversy.

The Fugitive Slave Act

The problem of slaves running away from their masters had never been particularly serious in the United States, but the new law was nevertheless notable as the South’s only serious victory wrung from the Compromise of 1850. The law authorized the appointment of commissioners who would preside over cases regarding fugitive slaves. They had the power to issue arrest warrants and – in a clearly partisan provision – were awarded five dollars each time it was decided that a slave should not be returned, but ten dollars if return was ordered. Slaves were not allowed trial by jury, even if they were claiming to be free.

Substantial fines were to be levied on any person obstructing the recapture of a runaway slave. Preventing one from being returned to his master exposed the offender to greater penalties, including imprisonment. Although the law mandated enforcement, a number of states in the North passed laws preventing state officials from co-operating in returning fugitive slaves. From time to time, abolitionists would mount raids with the intention of rescuing slaves from commissioners’ hearings, and these raids occasionally resulted in scuffles. The fact that the law was actively resisted across much of the North made it largely irrelevant in practice.

Long-Term Effects

Despite the tensions surrounding aspects of the Compromise, the package as a whole was broadly popular, and was seen as a force for peace and unity within the United States. However, the repeal of the Missouri Compromise by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 brought an end to this period of peace, and within a few years led to the crisis of secession that gripped the country in the months leading up to the outbreak of the Civil War itself. The 1850s saw both a polarization of views between the North and South – as evidenced by the vastly differing reactions to the publication of the novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin – and increasingly rapid expansion of the North’s industrial might. This last factor proved to be of crucial importance in the outcome of the Civil War.