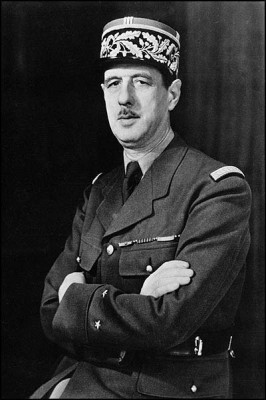

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was the President of France’s Fifth Republic and the leader of the French resistance against Germany in World War II. An imposing figure, standing at six feet four inches tall, he became a figurehead, not only for the French people, but for much of the world.

Early Life

Charles de Gaulle was born on November 22, 1890 in Lille, France. He was raised in a military family. Henri, his father, had been an officer in the Franco Prussian War. Charles’ mother, Jeanne, also came from a military family. Charles had a sister and three brothers.

De Gaulle attended College Stanislas in Paris and then served in the infantry. He attended the French military school, St. Cyr, and graduated with honors in 1911. This made him well positioned to serve in World War I. During the war, he was wounded four times and was finally captured at Verdun in 1916. After the war, he continued to serve in the French Army in Poland. De Gaulle then returned to St. Cyr to teach military history. De Gaulle married Yvonne Vendroux in 1921. They were so private that some people were somewhat surprised to learn that he was married. The de Gaulles had three children, a son and two daughters.

Between World War I and World War II, de Gaulle held several military positions and continued to teach at the French War College. He wrote the books The Edge of the Sword in 1932 and The Army of the Future in 1934 in which he posited his strategies for successful warfare. Ironically, though much of the French military establishment ignored de Gaulle’s books, the Germans studied them and used them.

World War II

The Germans invaded France in May of 1940 and de Gaulle was put in charge of one of France’s four armored divisions. On May 17, he launched a tank attack on German tanks at Montcornet. The Germans retreated, but temporarily. Still, this small and short-lived victory was enough for the French government to promote de Gaulle, who was then a colonel, to the rank of Brigadier General. He kept the rank of Brigadier General for the remainder of his life. The French government then appointed de Gaulle as the Undersecretary for War. However, only days after he was given his appointment, France surrendered to Germany.

The Germans invaded northern France in 1940 by marching through neutral Holland and Belgium and therefore avoided the difficult, mountainous border between Germany and France. The Nazi conquest was swift and easy and the French resistance collapsed while the French forces fled to the south. De Gaulle was in Great Britain when much of this was happening. He sent a message to the French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud, informing him of the British government’s proposal to merge Britain and France into one country with one military to beat back the Germans. But Reynaud’s cabinet refused.

De Gaulle returned to France. When he learned that Marshal Petain wanted to sign an armistice with Germany, he and some of his senior officers returned to London. In July of 1940 de Gaulle was court-martialed. His sentence would have been four years in prison. Less than a month later, he was court-martialed again, this time for treason. The verdict this time was a death sentence.

German Occupation and Resistance

The Germans occupied over half of France, including the Atlantic and the Channel coasts. They allowed something of a government to exist in the parts of France that they did not occupy. This was the antidemocratic government at Vichy, led by Philippe Petain.

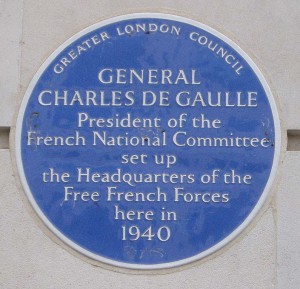

De Gaulle simply would not accept France’s surrender, nor the leadership of Marshal Petain, who had been his regiment commander. Petain had cooperated with the Germans, which de Gaulle found intolerable. While in London he broadcast messages to France. The broadcasts heartened the French people, especially the French resistance. His “Appeal of June 18th” urged the French to resist their German occupiers. He reminded the allies that the war was not yet over. To do this broadcast, de Gaulle had to get permission from Prime Minister Winston Churchill to use the offices of the BBC from Broadcasting House. Interestingly, there are no existing recordings of the speech.

Charles de Gaulle did not just make broadcasts to occupied France, but organized the Free French forces in England and some of France’s colonies. In September, 1941 he became President of the French National Committee. He was still living in London. In 1943, the Allies accepted de Gaulle as the leader of the “Fighting French.”

De Gaulle not only disdained Marshal Petain, but every one of the French forces that were cooperating or had cooperated with the Nazis. When the Allies tried to liberate Algiers in November 1942 it had first been arranged that General Henri Giraud lead the Allies into the country. However, Giraud could not get into the country in time. The administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt turned to Admiral Jean-François Darlan, the commander-in-chief of the French navy. Darlan happened to be in Algiers because one of his sons was sick. Darlan agreed to cooperate with the Allies, but the problem was that he had been a Nazi collaborator during the German occupation of France. When Petain heard of the Darlan plan he vetoed it. De Gaulle also denounced Darlan from London. Under pressure from not only de Gaulle, the Vichy government and some quarters of the United States, the Darlan arrangement fell apart. Darlan was later assassinated under murky circumstances.

Still, thorny relations with de Gaulle and the Allies continued throughout much of the war. During the Casablanca Conference in Morocco in 1943, Roosevelt wanted de Gaulle and Giraud, who was the leader of the French troops in North Africa, to come to some kind of accommodation. Giraud was eager to work with Roosevelt and Churchill, but de Gaulle refused to work with Giraud. He could never get past the fact that Giraud had worked with the Nazis. He only relented, a bit, when Churchill threatened to cut off his money in England. Roosevelt, Churchill and Giraud were all in Morocco at the time, and de Gaulle finally agreed to visit.

Still, when de Gaulle reached Casablanca he refused to receive Giraud. Not only that, he dramatically snubbed the British delegation. Finally, Roosevelt had to pressure de Gaulle. De Gaulle presented himself to Roosevelt at the President’s villa and they had what everyone believed was a private meeting. However, it was not private at all, as Mike Reilly, Roosevelt’s secret service guard, was listening behind some curtains with his gun un-holstered just in case. De Gaulle knew, but said nothing. In the end he agreed to work with Giraud.

De Gaulle would admit in his memoirs that much of the reasons for his acquiescence was due to Roosevelt’s charm and his sense of honor. However, he was not as cozy with Winston Churchill, who flew into a diatribe at the very moment de Gaulle was prepared to shake hands with Giraud for the cameras. Once again, de Gaulle shook hands with Giraud at the urging of Roosevelt, who genially ignored Churchill’s outburst. De Gaulle and Giraud disliked each other so much, however, that their handshake was too brief for the cameras to capture. They had to shake hands a second time.

In May of 1943, de Gaulle moved his headquarters to Algiers. A month before that he nearly lost his life in a plane crash. It was determined that the plane was sabotaged. De Gaulle always believed it was the Allies, despite his cordial relations with Roosevelt and General Eisenhower. He was in Britain on D-Day, but worried that the Allies would set up a government in France without his input. His relations with Churchill, which had never been warm, deteriorated.

Victory and Conflicts with Allies

Still, de Gaulle marshaled the forces of the Free French and troops from the French colonies. They landed in the south of France and liberated a great deal of the country. This was called Operation Dragoon. Later, the French forces would join up with the Allies to liberate the rest of France from the Nazis. On June 14, Charles de Gaulle at last returned to France and set up Bayeux as Free France’s capital city. He then returned to Algiers.

De Gaulle came to the White House on July 6, 1944 and was treated almost as a head of State. Earlier that morning, Roosevelt had recognized the French Committee of National Liberation as the de facto government of France. Roosevelt’s health was failing, and he and de Gaulle both understood then that the war was coming to an end. They needed to smooth out relations between the French Committee of National Liberation and the United States. Roosevelt needed to know that the French underground would cooperate fully with the American soldiers. This would be the last meeting of the two world leaders.

De Gaulle insisted that Paris be liberated by French troops and received consent from General Eisenhower. The French troops were the first to enter the city. De Gaulle came to Paris with the Allies in August 1944, but not without conflict. He was shot at at least twice by Vichy revanchists and he was even shot at as he walked down the aisle of the cathedral of Notre Dame. He was unhurt. Still, he eventually found it wise to ask for American back-up, given the Vichy revanchists and bursts of German retaliation. On August 29, 1944 Eisenhower sent the 28th Infantry Division into Paris.

By September 1944, de Gaulle was the head of the provisional government. He installed many of his Free French colleagues in positions of power. He toured the countryside and saw firsthand the terrible damage that had been wrought by the war. Though a quiet individual, he raised people’s spirits by having them sing “La Marseillaise” and with cries of “Long Live France!” He spent much of the next few months purging the French government of the last of the Vichy supporters. His allies in Britain and the United States did note that de Gaulle was as domineering with them as he had ever been. Still, despite de Gaulle’s difficult behavior, France was awarded a seat on the emerging United Nation’s Security Council during the Yalta Conference of February, 1945.

Roosevelt invited de Gaulle to a meeting in Algiers after the Yalta Conference, but de Gaulle denied him. The snub was so shocking that Roosevelt rebuked him during a session of Congress. Yet, when Roosevelt passed away on April 12, 1945, de Gaulle declared a period of official mourning and sent a telegram to the new President, Harry Truman. Unfortunately, de Gaulle’s relations with Truman were not warm either. French troops almost came into conflict with U.S. troops soon after when they were ordered to surrender certain German occupation zones. De Gaulle was forced to back down.

Finally, in May 1945, the Germans surrendered. They surrendered to the British and the Americans at Rheims and the Germans and the French signed an armistice in Berlin. De Gaulle seemed to not to want to acknowledge any help from the Allies in liberating his country. He dismissed the British Hadfield Spears Ambulance Unit when it had the gall to drive in the victory parade bearing both the Union Jack and the Tricolour. This despite General Edward Spears having personally flown de Gaulle to England in 1940 and his wife having been a nurse with the Free French in Northern Africa and southern Europe. Then, de Gaulle tried to occupy Val d’Aoste in Italy despite American objections. Truman was so furious that he cut off all arms supplies to France. There were other arguments in the Middle East. Again, French forces almost came to blows with the British in Syria. The Potsdam Conference would also aggravate de Gaulle when the participants decided to divide Vietnam between Great Britain and China, though Vietnam had been a colony of France for over a century. When de Gaulle sent forces to Indochina after Japan surrendered in August of 1945, the Vietnamese resisted.

In November 1945 the fledgling French government elected Charles de Gaulle as its head. But, given little support by the left-wing of the government and unable to support the Communist factions in the government, de Gaulle resigned on January 20, 1946. However, he would return, and the next phase of his powerful political life would begin.