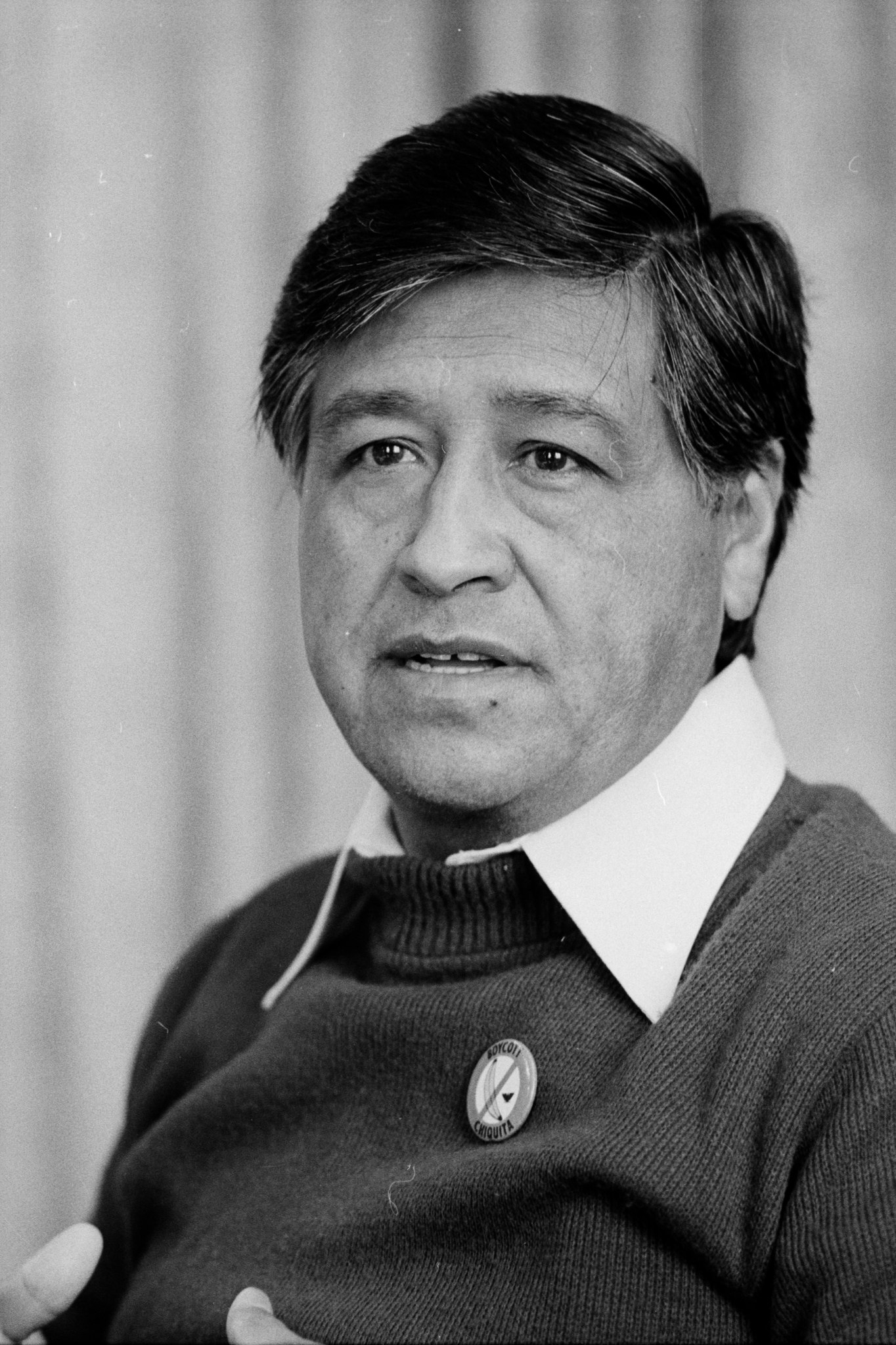

César Chávez was a transformative figure in American history, known for his dedication to improving the working conditions and lives of farm workers. Born in Yuma, Arizona, in 1927, Chávez experienced the hardships of migrant labor early in life. His family lost their farm during the Great Depression and became migrant farm workers. These early experiences deeply influenced Chávez, instilling in him a strong sense of justice and a desire to fight for workers’ rights.

Early Life and Influences

César Chávez’s early life was a profound journey through adversity, deeply influencing his future path as a leader and activist. Born into a Mexican American family, Chávez’s childhood was a narrative shared by many in his community, one where poverty and discrimination were everyday realities.

Growing up during the Great Depression, Chávez’s family faced significant financial hardships. This economic struggle led to the loss of their farm, a pivotal moment that thrust the family into the life of migrant farm workers. As a result, Chávez’s childhood was transient and unstable. The family moved frequently, traversing the landscape in search of seasonal agricultural work. This constant movement meant that Chávez attended more than 30 different schools as a child. However, these schools were often segregated and offered limited educational opportunities to Mexican American students, reflecting the prevalent racial discrimination of the era.

Chávez’s education came to an early end after completing the eighth grade. The financial pressures on his family required him to enter the workforce full-time, joining them in the fields. This shift from student to laborer at such a young age was a critical transition in his life. It exposed him firsthand to the harsh realities of agricultural labor – long hours, meager pay, and often deplorable working conditions. Additionally, Chávez witnessed the pervasive racial discrimination that farm workers of Mexican descent faced, an injustice that deeply affected him.

These formative years were more than just a time of hardship; they were a period of awakening for Chávez. The injustices he experienced and observed during his early life were not just individual grievances but part of a larger systemic problem faced by farm workers, especially those of Hispanic heritage. This realization was the cornerstone of his later activism. The resilience he developed during these challenging times, combined with a growing awareness of social injustice, laid the foundation for his future role as a champion for the rights of farm workers.

Rise as a Labor Leader

César Chávez’s journey to becoming a pivotal labor leader began in earnest during the 1950s, a period that marked a significant transformation in his life and career. His involvement with the Community Service Organization (CSO), a notable Latino civil rights group, was a crucial chapter in this journey. The CSO was an organization dedicated to improving the conditions and rights of Hispanic communities in the United States, and it was here that Chávez cut his teeth as an organizer and leader.

While at the CSO, Chávez honed his skills in community organizing, advocacy, and leadership. He was deeply involved in various initiatives, including voter registration drives, battling racial and economic discrimination, and advocating for labor rights. This experience was invaluable, teaching him not only the strategies and tactics of grassroots organizing but also the power of collective action and community solidarity.

However, it was during his time with the CSO that Chávez began to identify a gap in the organization’s focus. He noticed that the specific issues and struggles of farm workers, many of whom were Mexican Americans like himself, were not being adequately addressed. Chávez felt a strong personal connection to these issues, rooted in his own experiences as a migrant farm worker. This realization led to a growing desire within him to direct his efforts specifically towards improving the lives of farm workers.

This focus eventually led to a divergence of paths with the CSO. Chávez saw the need for an organization dedicated exclusively to the cause of farm workers, one that could fight for better wages, working conditions, and overall treatment. Acting on this vision, in 1962, he founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). The NFWA was a bold step, marking the beginning of a new era in labor activism, particularly for agricultural laborers.

The NFWA, which later evolved into the United Farm Workers (UFW), became a seminal force in the labor movement. Under Chávez’s leadership, it grew into a powerful voice advocating for the rights and welfare of farm workers. The UFW organized strikes, negotiated contracts, and worked tirelessly to improve the lives of its members. It also pioneered innovative tactics in labor activism, including consumer boycotts and nationwide awareness campaigns.

The Fight for Farm Workers’ Rights

Central to Chávez’s approach was his unwavering commitment to nonviolent methods. He drew inspiration from renowned figures such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., whose philosophies of peaceful resistance and civil disobedience influenced his tactics and approach.

A pivotal moment in Chávez’s leadership was the Delano grape strike in 1965, a landmark event in the history of American labor movements. This strike was not just a labor dispute; it was a moral call to action. The conditions that farm workers faced in the vineyards of California were harsh. They labored for long hours under the scorching sun, received meager wages that barely covered basic needs, and worked without basic labor rights, such as health insurance or job security. Chávez, deeply moved by these injustices, organized the strike to demand fair wages, humane working conditions, and respect for the dignity of farm laborers.

The strike began in Delano, California, a major center for grape cultivation. It was a bold move, as it challenged some of the most powerful agricultural businesses in the state. Chávez and the UFW called on the farm workers to stop working, a call that was answered with an overwhelming show of solidarity. The strike quickly gained momentum, drawing national attention to the plight of farm workers.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Delano grape strike was how it galvanized public support. Chávez understood the power of public opinion and used it to the workers’ advantage. He organized marches, boycotts, and public relations campaigns to draw attention to the strike and the conditions under which farm workers labored. The boycott of California grapes became a national movement, with consumers across the country standing in solidarity with the farm workers.

The strike also highlighted Chávez’s skill in coalition-building. He reached out to other labor unions, student groups, religious organizations, and civil rights activists, creating a broad base of support for the farm workers’ cause. This diverse coalition was instrumental in applying pressure on the grape growers and bringing national attention to the issue.

The Delano grape strike lasted five years and culminated in a significant victory for the UFW and the farm workers. The growers eventually agreed to sign union contracts, providing better wages and working conditions for the workers. This victory was a testament to the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance and the power of organized labor.

Chávez’s leadership during this time was not just about leading strikes and organizing boycotts; it was about lifting the voices of the marginalized and empowering them to stand up for their rights. His ability to inspire and mobilize people, coupled with his strategic use of nonviolent methods, made the fight for farm workers’ rights a central issue in the broader struggle for social justice in the United States. The Delano grape strike and other campaigns under Chávez’s leadership transformed the landscape of labor rights, not only for farm workers but for all laborers seeking fair and humane treatment.

Personal Sacrifices and Leadership

One of the most striking examples of Chávez’s sacrifices was his 1968 hunger strike. Lasting 25 days, this fast was not merely a protest but a deeply personal act of penance and spiritual reflection. Chávez undertook this hunger strike in response to the increasing violence surrounding the labor disputes and as a means to reaffirm his commitment and that of the movement to nonviolent methods. The fast was a poignant reminder of the struggle and suffering of the farm workers, highlighting the stark contrast between their humble demands and the harsh realities they faced.

Chávez’s hunger strikes had a profound impact both on the public perception of the farm workers’ struggle and on the labor movement as a whole. These actions captured the attention of the national and international media, bringing the plight of the farm workers into the living rooms of millions of Americans. The hunger strikes stirred public empathy and support, drawing many who might otherwise have been indifferent to the cause.

Moreover, these sacrifices underscored Chávez’s authenticity and dedication as a leader. In an era where leaders were often removed from the struggles of those they represented, Chávez stood out as someone who was willing to endure the same hardships he was fighting against. This deep alignment with the workers’ experiences earned him a great deal of respect and loyalty among the farm workers and their supporters.

Chávez’s hunger strikes also had a galvanizing effect on the labor movement. They served as a rallying point, reminding the workers and their allies of the moral and ethical dimensions of their struggle. These acts of self-denial brought a renewed vigor to the movement, reinforcing the commitment to nonviolence and solidarity among the farm workers and their supporters.

Legislative and Cultural Impact

César Chávez and the United Farm Workers (UFW) were instrumental in effecting monumental legislative and cultural changes, significantly altering the landscape of labor rights in the United States. Their relentless activism and advocacy bore fruit in numerous ways, perhaps most notably in the enactment of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. This landmark legislation was a direct outcome of their efforts, representing a major victory for farm workers and a significant milestone in labor history.

The California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975 was groundbreaking. For the first time, it granted farm workers in California the right to collective bargaining, allowing them to negotiate wages, working conditions, and other employment terms with their employers. This was a fundamental shift in the power dynamics between farm workers and agricultural businesses. Prior to this, farm workers had been excluded from many of the labor protections afforded to other workers, which had left them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. The act was a recognition of their rights and a testament to the effectiveness of the UFW’s advocacy.

Beyond legislative achievements, Chávez’s influence profoundly impacted the cultural landscape. He became a symbol of resilience and empowerment for marginalized communities, particularly among Hispanic and Latino Americans. His work transcended the boundaries of labor rights, intertwining with broader movements for civil rights and social justice. Chávez’s advocacy highlighted the interconnectedness of various social issues, including racial discrimination, economic inequality, and environmental justice.

Chávez and the UFW were also pioneers in integrating environmental concerns into their labor activism. They drew attention to the harmful effects of pesticides not only on consumers but also on the farm workers who were regularly exposed to these chemicals. This emphasis on environmental health was ahead of its time, contributing to the burgeoning environmental justice movement. By highlighting the links between labor conditions, health, and the environment, Chávez expanded the scope of what labor activism could encompass.

Legacy and Recognition

As a cultural icon, Chávez symbolized the resilience and aspirations of workers, particularly those from marginalized communities. His story is not just one of struggle but also of hope and relentless pursuit of justice.

The commemoration of Chávez’s birthday on March 31 as César Chávez Day in various states across the U.S. is a reflection of his enduring influence. This day is not merely a memorial; it serves as an annual reminder of the ongoing struggles for workers’ rights and social justice. It is a day of reflection, celebration, and, most importantly, a call to action to continue the work that Chávez dedicated his life to.

In 1994, Chávez was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States. This recognition was a significant acknowledgment of his contributions and sacrifices. It symbolized the nation’s respect and gratitude for a man who tirelessly fought for the rights and dignity of others, often at great personal cost.

Chávez’s journey was not without its challenges. He often faced formidable opposition from powerful agricultural interests who were threatened by his efforts to unionize farm workers and improve their working conditions. Additionally, there were times of internal strife within the UFW, as well as criticism of his leadership style and strategies. These challenges were substantial, but they did not deter Chávez. Instead, they served to strengthen his resolve and commitment to his cause.

Despite these obstacles, Chávez’s unwavering dedication to justice and equity left an indelible mark on American society. His life and work redefined labor activism and expanded the scope of social justice. He showed that change is possible through peaceful means, solidarity, and perseverance.

Chávez’s influence extends beyond the boundaries of the United States. His approach to labor rights and social justice has inspired movements around the world. His story is a powerful reminder of the impact one individual can have in the fight against inequality and injustice.