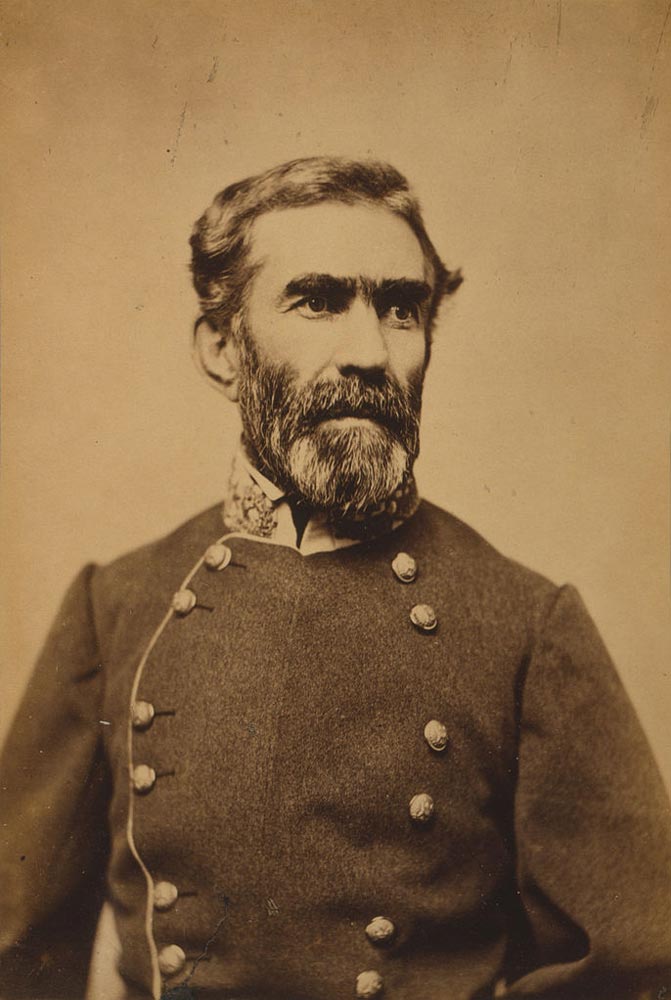

| Braxton Bragg | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Mar. 22, 1817 Warrenton, North Carolina |

| Died | Sep. 27, 1876 (at age 59) Galveston, Texas |

| Allegiance | United States of America Confederate States of America |

| Years | 1837–56 (USA) 1861–65 (CSA) |

| Rank | Brevet Lieutenant Colonel (USA) General (CSA) |

| Battles/wars | Second Seminole War Mexican-American War Siege of Fort Brown Battle of Monterrey Battle of Buena Vista American Civil War Battle of Shiloh Battle of Perryville Battle of Stones River Tullahoma Campaign Battle of Chickamauga Battles for Chattanooga Second Battle of Fort Fisher Battle of Bentonville |

Braxton Bragg (1817-1876) was first an officer in the United States Army and, later, a Confederate Army general. In the American Civil War, he commanded the Army of Mississippi, but he was recalled after a damaging loss at the Battle of Chattanooga. In later life, Bragg became a civil engineer, with achievements in harbor design, railroads and water provision.

Early Life

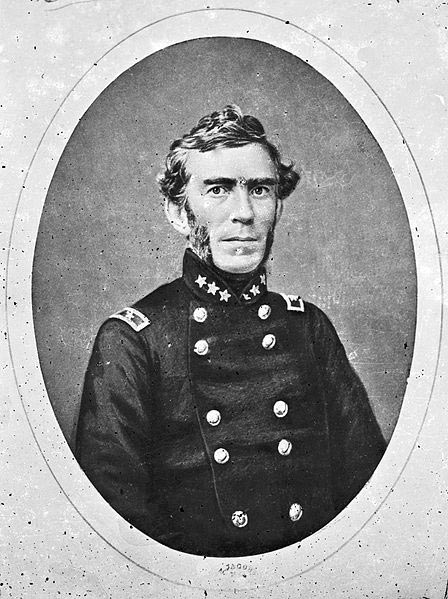

Bragg was born in Warrenton, North Carolina. His family was quite distinguished. His brother Thomas became the Attorney General of the Confederacy, while his brother-in-law, Don Carlos Buell, was a Union general. Bragg himself attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1837. On his graduation, he received a commission in the 3rd U.S. Artillery as a second lieutenant. Bragg’s main achievements in early life came in the Mexican-American War of the late 1840s. After leaving the army in 1856, he had spells as a Louisiana sugar planter and as that state’s Commissioner of Public Works.

He was several times recognized for his bravery, eventually winning a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel after the U.S. victory in the Battle of Buena Vista. Bragg was known for his strict adherence to regulations and for his disciplinarian tendencies: the commandant at one of his posts told him that he had “quarreled with every officer in the army” and so now had nobody left to quarrel with but himself. Perhaps because of his strictness, Bragg was not universally popular with his men: more than once there were reports of assassination attempts.

Civil War Service

At the start of 1861, Bragg held the rank of colonel in the Louisiana Militia. On February 20, he was promoted to the rank of major general and placed in charge of the forces in the area of New Orleans. However, the following month, he was transferred to the Confederate States Army as a brigadier general, in which role he took command of forces in western Florida such as those in the vicinity of Pensacola. By September, he was a major general, with a widening area of command that included Alabama. In October, the Army of Pensacola also became a part of his command.

In 1862, Bragg and his forces took part in two highly significant skirmishes: the Battle of Shiloh and the Siege of Corinth. At Shiloh on April 6, General Albert Sidney Johnston, the Confederate commander, was killed and replaced as by General P.G.T. Beauregard. As a result, Bragg was made up to be one of just eight full generals in the entire history of the Confederate Army. In this role, he was assigned to take charge of the Army of the Mississippi. In June 1862, when Beauregard’s illness had forced his departure from the scene, Bragg was made commander of the Army of Tennessee in his stead.

Bragg decided in August 1862 that he should launch an invasion of Kentucky. His thinking was that by doing so, he would be able to excite those in the border states who were supportive of the aims of the Confederacy, so pushing the Union troops commanded by his brother-in-law back to the Ohio River or even beyond. Bragg therefore took his own forces to Chattanooga and from there moved north, in conjunction with a separate army commanded by Lt. General Edmund Kirby Smith. Bragg won a victory at Munfordville, capturing more than four thousand Union soldiers before moving on to Bardstown.

Decline and Defeat

Bragg attended Richard Hawes’ inauguration as Kentucky’s provisional governor on October 4 and four days later, Bragg’s and Buell’s forces met at Perryville. Although tactically the battle was a victory for the Confederacy, the fact that Bragg then took his forces back to Knoxville meant that it qualified as something of a failure in strategic terms, since he had not been able to press home his advantage and complete the invasion of the state of Kentucky.

Bragg attended Richard Hawes’ inauguration as Kentucky’s provisional governor on October 4 and four days later, Bragg’s and Buell’s forces met at Perryville. Although tactically the battle was a victory for the Confederacy, the fact that Bragg then took his forces back to Knoxville meant that it qualified as something of a failure in strategic terms, since he had not been able to press home his advantage and complete the invasion of the state of Kentucky.

After an inconclusive encounter at the Battle of Stones River in central Tennessee, Bragg was almost relieved of his command when Confederate President Jefferson Davis gave General Johnston, who was in overall command of the Western Theater, the power to do so. However, after going to see Bragg, Johnston decided against removing him. Bragg’s forces were pushed back, but in mid-September they halted their retreat and turned to face Rosencrans’ men at the Battle of Chickamauga. Here the Confederacy won a signal victory, their greatest success in the West in the entire Civil War.

Bragg decided to lay siege to Chattanooga, but his plan was thwarted when Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union succeeded in relieving Rosencrans. In November, Bragg’s troops were badly beaten at the Battle of Chattanooga, a reversal which sparked alarm in the high command of the Confederacy. Generals Polk, Longstreet, and Hardee all told Jefferson Davis that they had no confidence in Bragg and – somewhat reluctantly, given his own personal sympathies for Bragg – Davis agreed to relieve Bragg of his command, appointing Johnston in his place.

The End of the War

Bragg was told to go to Virginia in February 1864 to serve as a military advisor to President Davis. This position had once been held with honor by none other than Robert E. Lee, but Bragg did not have Lee’s abilities and proved to be somewhat lacking in effectiveness in the post. As a result, he was moved once again, this time to oversee defenses in a variety of Confederate cities. These included Wilmington, Augusta, Savannah and Charleston before, at the beginning of 1865, he returned in the same role to Wilmington.

Again, Bragg proved an underwhelming commander, in particular at Fort Fisher, where the loss of the city could be directly attributed to his confused and ineffective command. By the time the war was nearing its end, Bragg had been reduced to commanding a corps that, in truth, was barely the size of a division in Johnston’s Army of Tennessee. He fought in the Battle of Bentonville and against Union General Sherman’s men in the Carolinas, eventually taking flight into Georgia as Lee surrendered to the Union army and final victory neared for the North.

In peacetime, Bragg worked as superintendent at the waterworks in New Orleans and rose to become Alabama’s chief engineer. In this role he took charge of Mobile’s harbor improvements, before moving states to become an inspector for Texas’s railroads. He died suddenly, after collapsing in the street while walking with a friend in Galveston, and is buried in Mobile. Despite Bragg’s uneven record as a soldier, the United States Army base at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, is named after him.