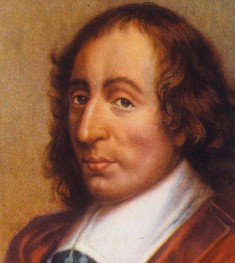

| Blaise Pascal | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Philosopher | |

| Specialty | Christianity |

| Born | June 19, 1623 Clermont-Ferrand, Auvergne, France |

| Died | Aug. 19, 1662 (at age 39) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

Blaise Pascal was born on June 19, 1623, in Clermont-Ferrand, France. Pascal’s father had a strong interest in science and mathematics and this may have had a great deal of influence on him. Even at a very young age, Pascal was showing quite a bit of talent for math and the sciences.

When he was just 16 years of age, he crafted a geometric proof on conic sections. He sent his proof to the theologians and mathematician Marin Mersenne. Mersenne was quite amazed at the revolutionary work the young man produced. In fact, to this very day, the proof is known as Pascal’s Theorem.

The Pascal Family

The Pascal family was heavily invested in bonds. They defaulted on the bonds in order to help fund the 30 Year War, leaving the family almost destitute. This would not break the spirit of young Pascal because he was still destined for greatness.

Eventually, after falling in and out of favor with one of the church’s cardinals in 1642, Pascal’s father was appointed a position where he was in charge of straightening out the tax records in the city of Rouen. The records were in utter chaos. To help his father, Pascal invented the prototype mechanical calculator. Before long, this device set the wheel in motion for the creation of the computer in the years ahead.

Pascal’s Philosophy of Mathematics

Pascal was not the only person to write and muse on the subject of the philosophy of mathematics, but his innovative insights into the subject were among the most profound. His seminal work, Of the Geometrical Spirit, was originally conceived as a mere introduction to a textbook.

Pascal built upon the introduction and turned it into a tome that spelled out the philosophical underpinnings of geometric theory. However, this treatise was not even published until 100 years after his death.

In the work, Pascal raised questions about being able to arrive at truths in geometry. He mentioned that all truths required other established truths to back up assertions which, in some cases, was not always easy to do. Hence, it could be said Pascal admitted some facets of geometry were based on theories that might be disproved at some point in time.

Within this work, Pascal also examined a unique theory of the subject of definitions. He pointed out some definitions are created by writers (formalism) and others are ones that have been crafted so that they can be better understood by larger audiences. While Pascal does not condemn the latter, he does note that the former is the more important because they are more rooted in the formalism of Descartes. The other definition is based more on creating identifiable traits.

On the Art of Persuasion

On the Art of Persuasion was another philosophical text Pascal wrote. This one dealt with axioms in geometry. More specifically, it dealt with how someone can become convinced of a particular axiom. To a degree, this work was one that not only looked at geometric theory, but how the human mind and belief system worked, at least from a microcosmic perspective.

On the Art of Persuasion was another philosophical text Pascal wrote. This one dealt with axioms in geometry. More specifically, it dealt with how someone can become convinced of a particular axiom. To a degree, this work was one that not only looked at geometric theory, but how the human mind and belief system worked, at least from a microcosmic perspective.

Pascal pointed out in this work that trying to arrive at conclusions through mere human methods was not likely going to occur. Rather, the proofs had to be arrived at through intuition that was connected to a profound belief and faith in God.

Pascal’s Later Years

Pascal had become very interested in the subject of religion later in life, and his interest was more than a passing one. In fact, he started to grow ill in 1659 and rejected medical help, opting instead for faith-based treatment. However, this led to his condition only becoming worse in time.

Pascal had written a great deal on the subject of religion and was involved with the Jansenist Christianity movement. His forays into theology did cause him some personal upheaval since such writing was automatically going to invite controversy. When Louis XIV sought to suppress the movement, Pascal wrote a response. His sister’s death did convince him to cease his involvement with the movement for his own good.

Pascal passed away on August 19, 1662. He left a great legacy as a mathematician and thinker who still influences people to this day.