The Battles of Lexington and Concord marked the start of open conflict between thirteen Colonists and the British. The battle took place on April 19th, 1775, in Middlesex County, Massachusetts Bay, near Boston. This battle marked the opening of armed hostilities between the Kingdom of Great Britain and its thirteen colonies in America.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord marked the start of open conflict between thirteen Colonists and the British. The battle took place on April 19th, 1775, in Middlesex County, Massachusetts Bay, near Boston. This battle marked the opening of armed hostilities between the Kingdom of Great Britain and its thirteen colonies in America.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord

The British Army infantry had occupied Boston since 1768 and were reinforced by their naval forces and marines. They were ordered to enforce the Intolerable Acts, which the British Parliament had passed and was meant to punish the Province of Massachusetts Bay for the “Boston Tea Party”.

The Battle of Lexington

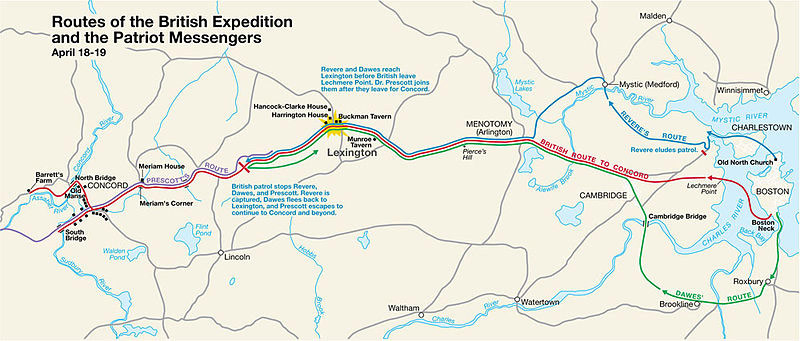

Though it has been called a battle, it was more of a skirmish. On April 18, 1775, a band of 80 militiamen stood guard in the village common, under the leadership of Captain John Parker. After standing guard most of the night without incident, they were about to be dismissed when word came that British troops were advancing. At sunrise on April 19, the advance guard of the British reached the commons of Lexington and ordered the assembled militia to disperse. Since there were no hostilities, Captain Parker of the militia, knew he was outmatched and knowing that the supplies had been hidden, expected the British to search, find nothing and return to Boston, as had happened before. He told the militiamen to go home.

The advanced British guard, led by Lieutenant Jesse Adair, carried out a flanking movement to protect his flanks and surrounded the militia to disarm them. However Major Pitcairn arrived with the balance forces and ordered the companies to stand down. The balance of the British troops, commanded by Colonel Smith waited further down the road to Boston. One of the British Officers called out to the militias to lay down their arms. With all the shouting and confusion at that moment, a shot was fired and the British troops, without orders, fired a barrage of shots to devastating effect. From Lexington, the British troops moved towards Concord.

The advanced British guard, led by Lieutenant Jesse Adair, carried out a flanking movement to protect his flanks and surrounded the militia to disarm them. However Major Pitcairn arrived with the balance forces and ordered the companies to stand down. The balance of the British troops, commanded by Colonel Smith waited further down the road to Boston. One of the British Officers called out to the militias to lay down their arms. With all the shouting and confusion at that moment, a shot was fired and the British troops, without orders, fired a barrage of shots to devastating effect. From Lexington, the British troops moved towards Concord.

The Battle of Concord

Having been forewarned, the militias in the Concord and Lincoln area were fortified in Concord. A contingent of militia, numbering 250, marched towards Lexington and came face to face with about 700 British troops. Since they were outnumbered, the militia returned to Concord and took up positions on a ridge overlooking the town. The militias abandoned Concord to the British troops and bided their time. They retreated to a hill about a mile to the north of Concord. From this vantage position they could keep watch on the activities of the British. The withdrawal of the militia proved to be advantageous as their ranks were strengthened by minutemen companies from surrounding areas.

The British search for arms and supplies did not amount to anything. They destroyed whatever they could find, including cannons. The militias in the meantime, under Colonel Barrett’s troops, decided to leave their vantage point on Punkatasset Hill, to a lower hilltop close to the North Bridge. When the militia advanced, the 4th and 10th companies, which held positions near the road, withdrew and left the hill under the control of the militia. The militia strength at this point totaled 400 men, against 95 of the British.

The militias under Colonel Barrett, decided to advance with loaded weapons, but were ordered not to fire, except in self-defense. The militias crossed the North Bridge and due to a poor defensive strategy by Captain Laurie, the British troops were put into a disadvantageous position. The ensuing firefight saw the British being outnumbered and outmaneuvered as they fled, abandoning the wounded, to the safety of their own lines. The militias were stunned by their success and quickly formed defensive positions on the hilltop 300 yards from the bridge, and another defensive position across the bridge, on a hill behind a stone wall.

Lieutenant Colonel Smith heard the exchange of fire and rushed reinforcements to help Captain Laurie and his men. A standoff ensued near the bridge. The British officers moved closer towards the bridge to assess the situation, but were not fired upon by the militias as they had been told to hold their fire. When the British came across their dead and dying comrades, one of whom appeared to have been mutilated, they were shocked and furious at the turn of events. They continued their original mission of searching and destroying military supplies of the militias. The British left Concord after lunch and this delay gave the militias additional time to muster more men and cut off the road back to Boston.

Lieutenant Colonel Smith heard the exchange of fire and rushed reinforcements to help Captain Laurie and his men. A standoff ensued near the bridge. The British officers moved closer towards the bridge to assess the situation, but were not fired upon by the militias as they had been told to hold their fire. When the British came across their dead and dying comrades, one of whom appeared to have been mutilated, they were shocked and furious at the turn of events. They continued their original mission of searching and destroying military supplies of the militias. The British left Concord after lunch and this delay gave the militias additional time to muster more men and cut off the road back to Boston.

The first hurdle the British faced was to cross a small bridge on the outskirts of Concord. The narrow bridge forced the troops to close ranks with just three soldiers abreast. As soon as the British crossed the bridge, the militia fired and in the exchange, at least two British troops were killed. About 500 militiamen had massed near the woods on Brooks hill further down the road from the bridge. They not only repulsed British efforts to dislodge them but also inflicted heavy casualties. When the British troops reach a curved road through a wooded area, the militias had set up an ambush. The British were caught in a cross-fire and suffered heavy casualties.

The militia ranks continued to grow, and they numbered about 2,000 men. Though the militias had gained the upper hand, superior British tactics ensured that they were not routed, and they scored some successes. However, they were running short of ammunition and were exhausted. The militias were on higher ground and constantly harassed the British troops. Two of the British Officers, Smith and Pitcairn, were either wounded or unhorsed. Some of the demoralized British troops surrendered. The rest ran forward in a mob. The planned withdrawal had turned into a rout of the British forces. British Officers struggled to regain control of their men. The possibility of the British surrendering was looming large, when they were reinforced by the arrival of Earl Perch and a brigade of 1,000 men with artillery.

Brigadier General William Heath took control of the militia and changed tactics. The militias were scattered and were told to snipe and fire from a distance, to prevent the effective use of cannon. The militias could inflict maximum casualties with least risk. The militias would ride ahead on horses, wait till the British came within range, fire and then disperse. The militias kept flanking the British and harassing them. When the British crossed from Lexington into Menotomy, further gun battles ensued. The British were forced into house to house fighting and there were many casualties. During this phase of the battle, Earl Percy lost control of his men, and they went on a rampage against the locals. The British Officers had a tough time in controlling their troops. By next morning, Boston was surrounded by a huge militia army of more than 15,000 men. The British lost 273 soldiers and the militias 94.

The battle of Lexington and Concord had set off the American Revolution and independence was only a matter of time.