The Battle of Teutoburg Forest took place in AD 9, in what is now present-day Kalkriese, in Germany. Methodical treachery and a well-planned ambush resulted in the slaughter of Roman troops that shocked the empire to its core. The defeat was so crushing that it is thought to be one of the most catastrophic events in Rome’s history.

Background

As a result of Drusus’ attacks on Germanic tribes in the years 11 to 9 BC, a Cherusci chieftain named Segimerus sent his son, Arminius, to Rome as tribute. Although Arminius grew up in the city as a hostage, he was given military training and eventually attained Roman citizenship and the rank of an equestrian. His father, meanwhile, was branded a coward by other Germanic chiefs for bowing down to Roman power.

At the beginning of AD 6, Gaius Sentius Saturninus, a senior military officer working with Tiberius, led a massive army against the king of the Marcomannic people, Maroboduus. Later in the year, however, the command of the army was transferred to Publius Quinctilius Varus, a general and administrative officer. Varus was sent to Germania to bring together the new Roman province.

Meanwhile, a massive revolt flared up in the Roman province of Illyricum, caused by grain shortages and high taxes. This development forced Tiberius to stop his military operations against Maroboduus because a significant portion of his troops needed to be sent over to Illyricum. Tiberius had eight legions at the time, and he had to send all of them to the revolt. Due to the severity of the situation, almost half of the empire’s legions eventually had to be deployed to the revolt. As a result, Varus was left with only three legions to take with him to Germany.

Nonetheless, he was expected to accomplish his task with limited troops, largely due to the ruthless reputation that he enjoyed in and outside the empire.

Arminius, the Traitor

Meanwhile, Arminius had completed his military education in Rome and had become Varus’ advisor. However, Arminius was playing a game of deception and was targeting Varus and his troops as his victims. Behind Varus’ back, he formed a coalition of Germanic tribes, including the Cherusci, Chatti, Bructeri, and Marsi. These tribes were usually hostile to each other but decided to agree to Arminius’ plan because they shared a common hatred for Rome. Varus was not perceptive enough to sense the danger and went headlong into his mission with limited troops. This was his tragedy.

While Varus was marching his troops to the winter camp on the Rhine, he received word of an uprising in the area. The news, of course, was just Arminius’ lie, intended to begin leading Varus to his death. Arminius’ men who informed Varus about the supposed rebellion made it sound as if the situation needed Varus’ quick response. Varus believed the report, not suspecting Arminius’ loyalty even for a moment.

The night before he led his troops to the supposed uprising, a Cheruscan named Segestes, Segimerus’ brother, advised Varus to arrest Arminius and his Germanic men. Varus took this advice lightly because he knew there was a grudge between Segestes and Arminius.

The next day, Varus started to lead his troops to suppress the uprising, but Arminius offered an alternate route that was supposed to shorten the travel time. The Romans were new to this route and were not aware that they were marching to their deaths. Soon after, Arminius informed Varus that he had to leave for a while to check on other Germanic tribes supporting the Romans. In reality, he met with other Germanic troops somewhere and started attacking Roman camps around the area. This step was crucial to Arminius’ plan to eliminate the possibility of help arriving at Varus later.

The Battle

Varus marched onto the unfamiliar terrain along with his three legions. Because of the narrow path, they were forced to abandon their fighting formation and simply marched in a line. As they trekked deeper into the forest, the trail became narrower and marshy as the rain started to pour.

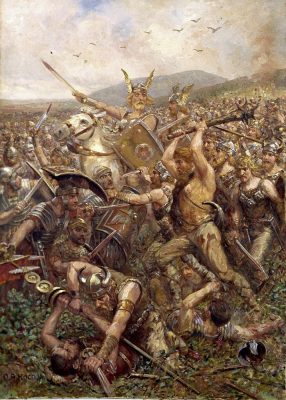

Another of Varus’ mistakes was that he did not think of sending out an advance party. Soon, the marching troops’ line extended to 20 kilometers, and at this state, they could no longer put up an effective fight when needed. But this was what the Germanic tribes were waiting for, and from behind the cover of trees, they attacked Varus’ men with javelins and swords.

The Roman line was rained down with spears, from the front to the end. When the night started to come down, the surviving Romans set up a defensive camp. At the first sign of light the next day, they tried to escape towards the open grasslands but, in the process, lost more men. The next night came, and they continued their attempts to escape.

They soon arrived at the base of a hill where their chances to further advance were restricted by a hill and a swamp on the other side. They looked in the direction of the woods and saw a wall that seemed to be built out of the earth. The Romans started to hear some rustling and, fearing that the enemy was about to butcher them, frantically tried to smash the wall. The wall held, and the Germans attacked them. Varus’ second-in-command, Numonius Vala, left his responsibilities and dashed off with other soldiers on horseback. Unfortunately for him, German cavalrymen chased him, and he was killed before he even cleared much ground. The barbarians hurled a ferocious attack and finished off the Romans. In the middle of the carnage, Varus killed himself, along with many of his men. Historians calculate the Roman deaths at around 20,000. The survivors were taken by the Germans as captives and cooked in boiling cauldrons as sacrifices to their gods.

When news of the terrible defeat reached Rome, the emperor Augustus was said to have repeatedly banged his head on the wall. The historian Seutonius writes that the emperor continually screamed, “Quintili Vare, legiones redde!” (Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!)