| The Battle of Stalingrad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Military Leaders | |||||||

| Military Units in Battle | |||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| Beginning: 270,000 men 3,000 artillery pieces 500 tanks 600 aircraft, 1,600 by mid-September At the time of the Soviet counter-offensive: 1,040,000 men: (400,000 Germans, 235,000 Italians, 200,000 Romanians, 200,000 Hungarians, 5,000 Croatians) 10,250 artillery pieces 500 tanks 732 (402 operational) aircraft |

Beginning: 187,000 men 2,200 artillery pieces 400 tanks 300 aircraft At the time of the Soviet counter-offensive: 2,500,000 men in total 1,143,000 men in Stalingrad area 13,451 artillery pieces 894-4,000 tanks 1,115 aircraft |

||||||

| Casualties and Deaths | |||||||

| Total: | Total: | ||||||

| est. 850,000 killed, missing or wounded including 107,000 captured (only 6000 survived the captivity and returned home to 1955) 900 aircraft (including 274 transports and 165 bombers used as transports) 1,500 tanks 6,000 artillery pieces |

Approx. 1,150,000 killed, missing or wounded including 478,741 killed and missing 650,878 wounded and sick 40,000 civilians dead 4,341 tanks 15,728 artillery pieces 2,769 combat aircraft |

||||||

| Part of World War II | |||||||

The Battle of Stalingrad is considered to be one of the turning points of World War II. It was fought between the Soviet Union and the Axis powers led by Nazi Germany, over a period of several months between August 1942 and February 1943. Enormous casualties were suffered by both sides. The Germany army suffered particularly heavy losses, bringing an effective end to the Nazi invasion of Russia. In fact, there were no further major German victories on the Eastern Front in the entire war.

Background

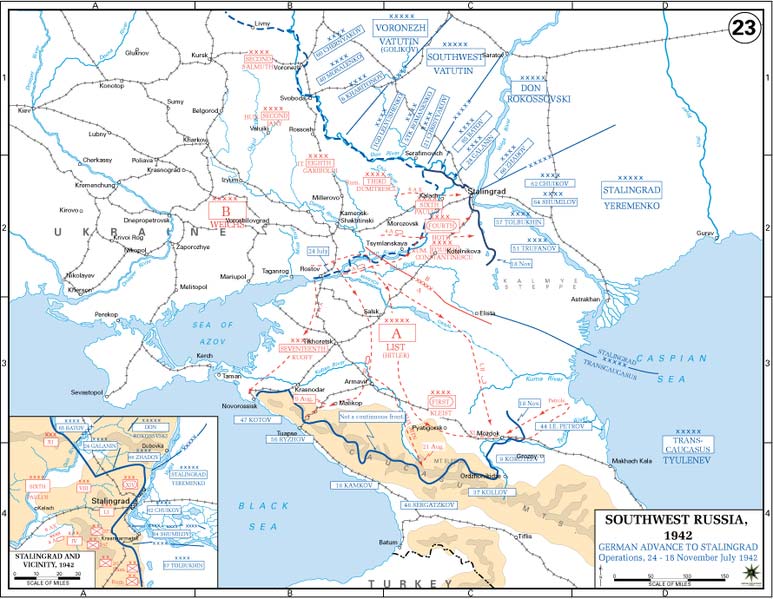

After the German advance on Moscow had been halted by the Red Army at almost the last moment, Hitler realized that he did not have sufficient numbers to launch an all-out assault along the front. Instead, he resolved to refocus German attacks on the southern Russian lands which were rich in oil. Operation Blue, as it was known, began in late June of 1942, surprised the Russians who had expected a renewed attack on Moscow. Nevertheless, strong resistance at Voronezh bought the Soviets sufficient time to call in reinforcements.

Hitler quickly became upset at what he saw as the slow progress of his armies, dividing them into two Army Group units named A and B. Army Group A had most of the armor and was ordered to secure the oil fields. Meanwhile, the more lightly armored Army Group B was told to proceed to Stalingrad and capture the city to prevent an attack on the German flank. Stalingrad was strategically vital both for its location on the Volga River and for its propaganda value. Renamed after Soviet ruler Josef Stalin, its fall would send a message to Moscow that Hitler hoped would cause a collapse in morale.

Preparating for Battle

The German drive toward Stalingrad was headed by the 6th Army under General Friedrich Paulus. This was supported by the 4th Panzer Army of General Hermann Hoth. At this early stage, around a quarter of a million German troops were involved, while Soviet forces numbered barely 180,000, although a few months later there would be more than one million men fighting on each side of the enormous battle.

The German drive toward Stalingrad was headed by the 6th Army under General Friedrich Paulus. This was supported by the 4th Panzer Army of General Hermann Hoth. At this early stage, around a quarter of a million German troops were involved, while Soviet forces numbered barely 180,000, although a few months later there would be more than one million men fighting on each side of the enormous battle.

As it became clear what the Nazis were intending, Stalin ordered General Andrey Yeryomenko to Stalingrad. When he arrived there, the general ordered that the city be stripped of supplies and prepared for close-quarters combat in the city itself. Many of the buildings were fortified in support of this aim. Some of the city’s civilian inhabitants were allowed to leave, but a large number remained on Stalin’s orders; he felt that a “living city” would give a greater incentive for his soldiers to defend it.

Battle Commences

Ahead of the advancing ground forces, planes under General Wolfram von Richthofen succeeded in establishing control of the skies over Stalingrad. Huge numbers of bombs were dropped, causing heavy civilian casualties. Meanwhile, Army Group B pushed on west, reaching the Volga to the south of the city by the first day of September. This cut off a supply line for the Soviets, who could now only bring in reinforcements by crossing the river under frequently heavy attack by German forces.

Ahead of the advancing ground forces, planes under General Wolfram von Richthofen succeeded in establishing control of the skies over Stalingrad. Huge numbers of bombs were dropped, causing heavy civilian casualties. Meanwhile, Army Group B pushed on west, reaching the Volga to the south of the city by the first day of September. This cut off a supply line for the Soviets, who could now only bring in reinforcements by crossing the river under frequently heavy attack by German forces.

Paulus and his 6th Army began to move into the city itself on September 13, about a week after arriving at the scene. Support was given by the 4th Panzer Army in the southern suburbs. The principal objective at this stage was the river’s landing area and a nearby hill, Mamayev Kurgan, as well as a major train station. The Russian defenders, commanded by Lt.-Gen. Vasily Chuikov, put up a very stiff defense despite their inferior numbers. Chuikov decided to reduce this disadvantage by remaining closely engaged with the Germans.

Fighting in the City

For a number of weeks, bitter street fighting raged in Stalingrad, with many soldiers expecting to live less than a day after being deployed. The increasingly ruined buildings of the city became home to snipers and guerrillas, making the city even more dangerous. The Soviet army’s desperate fighting could not prevent them from being forced back into just 10% of the city by late October, although the Nazi troops had endured huge casualties to get to that point. Hitler ordered that Romanian and Italian soldiers be brought in to guard the flanks, while a number of aircraft were transferred from the North African campaign.

While the street fighting went on, Stalin ordered Zhukov to gather sufficient forces to mount a counter-attack. He, along with General Aleksandr Vasilevsky, massed armies on the wide steppe plains both south and north of the city, and on November 19, Operation Uranus was launched. In this assault, three Russian armies crossed the Don River to destroy the Romanian Third Army. The following day, the Romanian Fourth Army was also shattered by a further attack from two Soviet armies. The Soviets took advantage of this confusion to encircle the city, then the German 6th Army.

The Siege of Stalingrad

With a quarter of a million Axis forces surrounded by the Russians, German generals pleaded with Hitler to allow them to mount a breakout. However, Hitler refused and insisted, with support from Goering, that air-drops could be used to re-supply the encircled soldiers. In the event, as Hitler had been warned, this was not possible and Paulus and his troops began to suffer ever more difficult conditions. Seeing what had happened, some Soviet forces closed in on Paulus while others pushed eastward. By early December, the Germans had been forced into such a small area that a break-out seemed the best option.

In the event, Operation Winter Storm, as the break-out attempt was called, was a failure. The Soviets replied with Operation Little Saturn in mid-month, pushing the Axis forces sufficiently back as to make relief of Stalingrad impossible. With the situation in the city now unbearable, Paulus sent word to Hitler asking to be allowed to surrender. Hitler refused the request and instead promoted him to field marshal – a symbolic act, as no German field marshal had ever been taken prisoner. Paulus was being told that he must commit suicide, although he declined to do so and was indeed captured on January 31. Two days later, the last German resistance was crushed.

Aftermath

Both sides in the Battle of Stalingrad suffered massive losses, with nearly half a million Soviet troops dying and over 600,000 suffering wounds, as well as about 700,000 Axis soldiers being killed or wounded. The desperate conditions of the siege had resulted in as many as 40,000 of the city’s civilian population falling victim either to bombing raids or starvation and disease. Critically, over 90,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner, most of whom would not survive to return home. A few weeks later, the Red Army launched a number of attacks over the Don River, pushing the German Army Group A out of the Caucusus region and securing the oil fields for the Soviets.