| Battle of Sari Bair | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| 8 divisions | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and Deaths | |||||||

| Total: | Total: | ||||||

| 20,155 | 12,000 | ||||||

| Part of the World War I | |||||||

The Battle of Sari Bar of 1915 marked the effective end of the Allies’ Gallipoli Offensive against the Ottoman Empire in World War One. The battle, which is sometimes known as the August Offensive or the Battle of the Nek, occurred when Anzac forces from Australia and New Zealand attempted to break the stalemate that had prevailed for some time and capture the Gallipoli peninsula in its entirety from the Ottoman Empire. The breakout attempt was a failure, and although some of the Ottoman lines were damaged, they held together sufficiently to prevent an Allied victory.

Background and Strategy

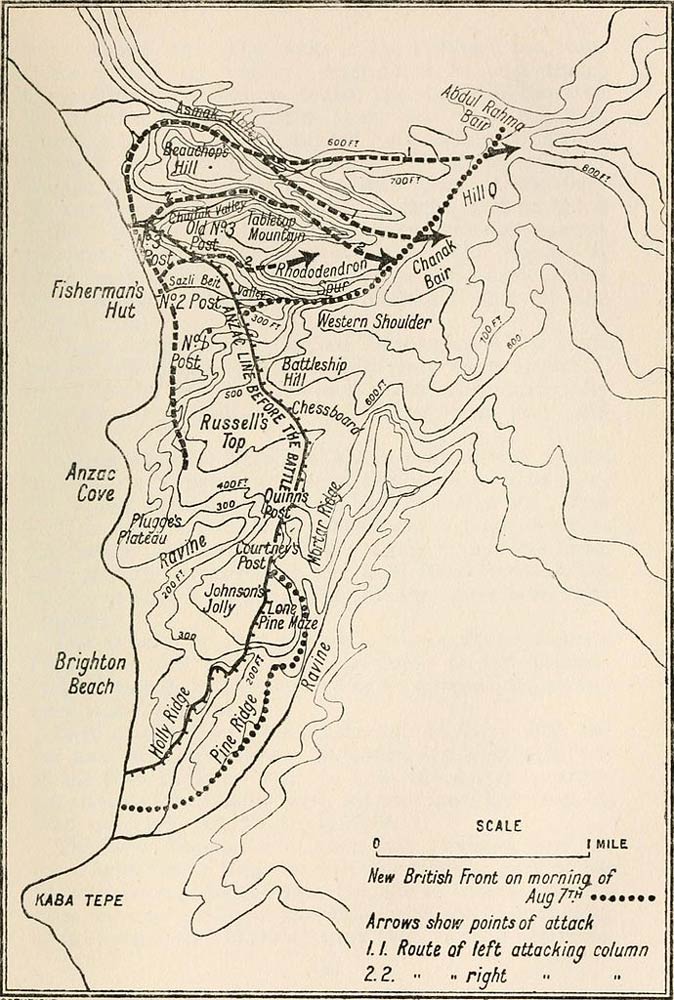

Sir Ian Hamilton, who was in charge of Allied forces in the Mediterranean, saw the attack as part of a three-pronged strategy which he termed the Suvla Offensive. This included landings at Suvla Bay as well as a holding move from Helles and a north-pointing attack from Anzac Cove aimed at bringing the Sari Bair hills under Allied control.

All these attacks would need to be successful in order to let Anzac forces gain mastery over the highlands of the peninsula’s interior. This would in turn allow the Ottoman troops to the south to be cut off, thereby gaining control over the Dardanelles, which was the Allies’ ultimate goal in the region.

Putting the Plan into Action

After some discussion, it was decided that the plan to be put into action on the Sari Bair front would involve a pair of brigades moving north along the coast, then turning eastward. The Australian and New Zealand Corps were increased in size from around 25,000 troops to an ultimate strength of 45,000 in preparation for the assault.

About half this number participated in the first advance, led by General Godfrey in the early hours of August 6, 1915. The forces were moving without complete knowledge of their ground, since Turkish snipers had prevented as much reconnaissance being carried out as they had desired.

Problems and Setbacks

In order to retain the crucial element of surprise, it was vitally important that the northward advance proceeded at speed, but during the actual event, it was significantly delayed. Problems encountered included the extreme summer heat of the region, maze-like terrain that made effective navigation difficult, and a serious outbreak of dysentery.

Godfrey’s troops were in fact nowhere near their initial objective – Hill Q – by the time night fell. Meanwhile, a diversionary advance heading south from Anzac Cove encountered such strong resistance that several Victoria Crosses were awarded for feats of bravery at Lone Pine.

Other Failed Attacks

The Lone Pine attack did not divert Ottoman attention as had been hoped. In fact, it made matters worse as the Turkish troops there were better placed to assist with the defense of Sari Bair.

Another supporting operation, close to Chunuk Bair, also failed as the troops were confronted with heavy artillery and their own small arms were largely ineffective against fortified trenches. General Birdwood continued toward Sari Bair the following day, but his New Zealand brigades held the ridge at Chunuk Bair for just two days. Meanwhile, a Gurkha battalion at Hill Q proved unable to capture it given a lack of reinforcements.

Aftermath of the Attacks

The Sari Bair operation turned on whether or not the Anzac forces could advance at a sufficient speed to take the ridge and give Allied troops time for consolidation. When this did not happen, thanks to a mixture of prevarication and confusion, the failure of the operation became all but certain. Although some fighting continued for two more days, by nightfall on August 10, this had largely ceased.

Both the Turks and the Anzacs were thoroughly exhausted, but it was the Ottoman defenders who had won the day. Despite casualties of up to 20,000, they had effectively destroyed the Allies’ breakout plans for the long term.