During the American Revolution, the Battle of Fort Washington occurred on November 16, 1776 near Washington Heights, New York. The battle, fought between approximately 3,000 American forces and approximately 8,000 British forces supplemented by Hessian troops, ended as a clear British victory when the fort’s entire garrison surrendered. With coordinated efforts, British troops were able to overwhelm the American defense of the fort and take control of this last remaining American stronghold in Manhattan.

During the American Revolution, the Battle of Fort Washington occurred on November 16, 1776 near Washington Heights, New York. The battle, fought between approximately 3,000 American forces and approximately 8,000 British forces supplemented by Hessian troops, ended as a clear British victory when the fort’s entire garrison surrendered. With coordinated efforts, British troops were able to overwhelm the American defense of the fort and take control of this last remaining American stronghold in Manhattan.

Structure and Value

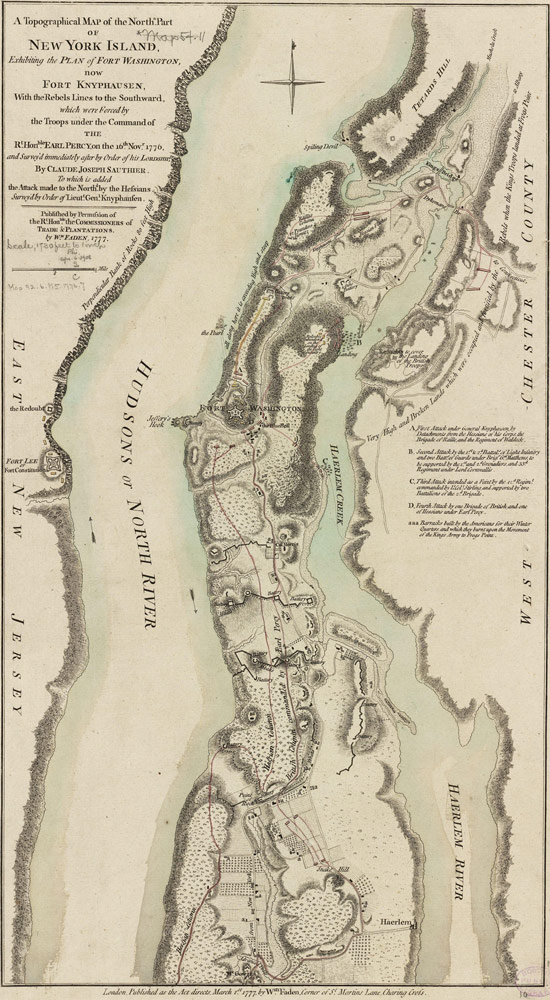

The eventual location of Fort Washington was identified as key to the American control of the Hudson River valley against British incursions. With a position on high land overlooking the Hudson River, the fort, in conjunction with Fort Lee across the river, was intended to protect the river from opposing warships upon completion. Construction of the fort required significant effort to bring enough soil to the location to construct the fort. Upon completion, the fort consisted of five earthen walls, each with a bulwark. The walls included openings for gun emplacements covering every angle and overlooked approximately four open acres surrounding the structure. In addition to the primary fort, numerous defenses surrounded the fort. Multiple gun batteries were placed in proximity at key strategic locations and lines of trenches and foxholes were dug into the surrounding hills.

Upon completion, Fort Washington controlled the high ground overlooking the Hudson River, thus protecting the American positions from warships. Between the elevation and defenses of Fort Washington and Fort Lee, British ships could not mount an adequate attack against the forts. As a result, the forts were considered critical to the American positions along the Hudson River even though all exterior defenses were not fully completed.

Prelude to Battle

Following the Battle of White Plains where American Commander-in-Chief George Washington and his army was defeated, British commander William Howe turned his attention to Fort Washington. The fort was one of the last American garrisons remaining on the island of Manhattan. Although Washington considered abandoning the fort and moving the remaining troops to New Jersey, he elected to continue manning the fort at the encouragement of General Nathanael Greene. Greene felt the strength of the fort was sufficient to hold off any British attacks and would help keep communication channels open.

In the months preceding the Battle of White Plains, minor skirmishes were fought along the approaches of Fort Washington, along with an attempt to fire on the fort from the water. Due to the fort’s strength, all attempts were turned back and Commander Robert Magaw, in charge of the garrison, became confident he could hold out in a siege through December of 1776, despite having only a small number of troops under his command. Unfortunately, his adjutant, William Demont, provided the details of the fort to the British when he deserted the American forces.

Following the Battle of White Plains, Washington divided his American army by committing a significant portion of his troops to prevent an invasion of the New England states and committing another portion to guard the Hudson Highlands and prevent further British advances. This left Washington with approximately 2,000 troops which he moved to Fort Lee. Based on his actions, Howe decided on attacking Fort Washington was the next step for the British forces and would significantly damage or destroy American strength in the area. He began making plans for a coordinated, multi-prong attack designed to overwhelm the fort’s defenses.

The Battle

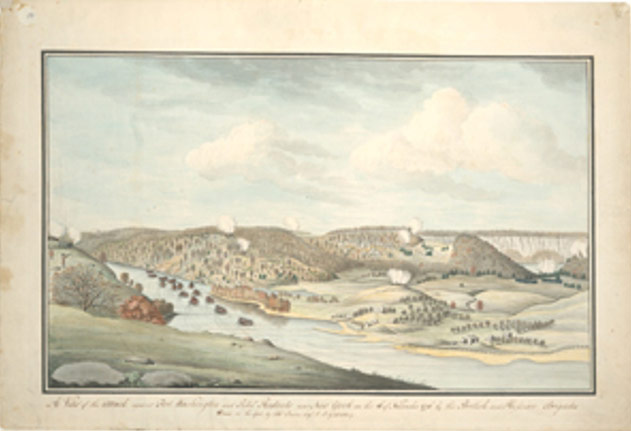

On November 16, Howe initiated the attack with forces approaching from three different directions. British forces attacked from the south and east. Hessian troops attacked from the north. While the northern assault was delayed because of the tides of the river, the southern and eastern assaults proceeded according to schedule with artillery support from the south and a British frigate.

On November 16, Howe initiated the attack with forces approaching from three different directions. British forces attacked from the south and east. Hessian troops attacked from the north. While the northern assault was delayed because of the tides of the river, the southern and eastern assaults proceeded according to schedule with artillery support from the south and a British frigate.

The southern defenses of Fort Washington, which were never fully completed, fell to a British charge after the American forces tried to hold off the British troops as they crossed the river. The eastern defenses also fell quickly to the British assault. While the southern and eastern defenses proved porous, the northern defenses held out longer but eventually collapsed against the onslaught of British troops. As each section of defense collapsed, the American troops withdrew from the trenches and exterior defenses to the fort itself.

When the British emissary, Captain Hohenstein, demanded the fort’s surrender, a messenger arrived from Washington. Washington, observing the battle from Fort Lee, sent the messenger to Magaw requesting the fort be held until night with the hopes the remaining forces could be evacuated under cover of darkness. Although Magaw requested four hours to consult with his officers and decide on the surrender request, Hohenstein demanded an answer within a half hour. With these constraints and with his men in danger, Magaw elected to surrender the fort instead of attempting to hold it against the opposing forces until nightfall. He attempted to gain concessions and better terms for his men as a condition of surrender without success.

The Aftermath

According to the terms of surrender, the American troops were allowed to retain their belongings. However, after the Hessian troops entered the fort, the evacuating Americans had most of their belongings taken from them. In addition, many of the surrendering troops were beaten, although the Hessian officers stopped the beatings quickly. Over 2,800 American troops were taken prisoner as a result of the surrender of Fort Washington. Of those troops, only 800 survived until a prisoner exchange approximately 18 months later.

Three days after the surrender of Fort Washington, American forces abandoned Fort Lee. The remaining American forces under Washington’s command fled across New Jersey and into Pennsylvania. The loss of Fort Washington damaged the morale of the American forces and colonies with the retreat of the main American army.

While the Battle of Fort Washington was a clear and decisive British victory, the movements of Washington and his army following the fort’s surrender created the circumstances for later battles. Despite losing the fort, troops and material captured by the British, Washington’s retreat into Pennsylvania set the stage for the future battles of Trenton and Princeton, both of which significantly accelerated the loss of morale caused by the defeat at Fort Washington.