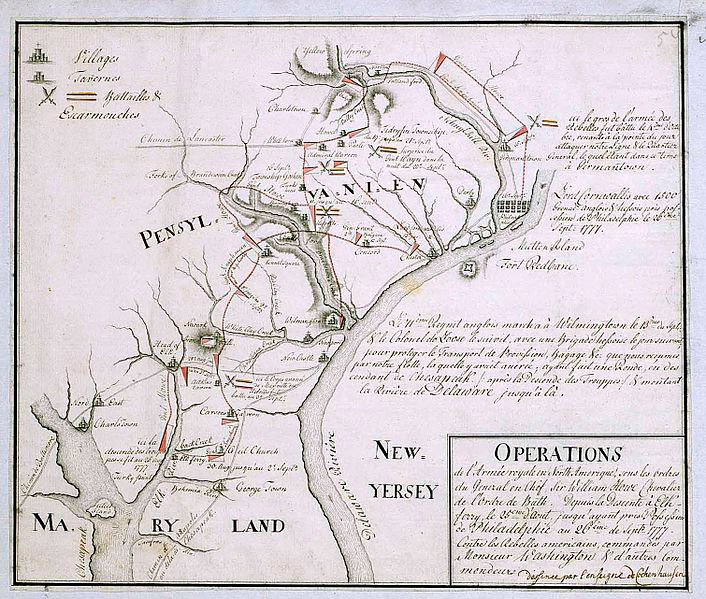

The foggy afternoon of September 11, 1777 marked a battle that would end the long period of frustration for the British army in North America. The Battle of Brandywine, or the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was a battle between the American army of Major General George Washington and the army of General Sir William Howe, comprising of British-Hessian army men. The battle was inevitable as both camps had been planning for the battle beforehand. The British were the victors of this battle, forcing Americans to withdraw towards Philadelphia, where the rebel capital resided. The main battle occurred miles before Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania while General Howe was executing a campaign to capture Philadelphia.

The foggy afternoon of September 11, 1777 marked a battle that would end the long period of frustration for the British army in North America. The Battle of Brandywine, or the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was a battle between the American army of Major General George Washington and the army of General Sir William Howe, comprising of British-Hessian army men. The battle was inevitable as both camps had been planning for the battle beforehand. The British were the victors of this battle, forcing Americans to withdraw towards Philadelphia, where the rebel capital resided. The main battle occurred miles before Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania while General Howe was executing a campaign to capture Philadelphia.

Howe’s Decisive Plan

Howe’s British-Hessian army sailed towards Elkton, Maryland, located in the northern Chesapeake Bay where they landed from York City. They immediately marched north where they brushed aside a number of American light forces in a few skirmishes. Washington then battled their troops behind Brandywine Creek. Howe’s plan was decisive. Part of his army battled in front of Chadds Ford, but the majority of his troops marched a long way to cross the Brandywine creek beyond Washington’s right flank. The American troops did not notice Howe’s army until they already reached a strategic location in the back of their right flank.

The Occupation That Would Last Almost A Year

The following hours that rolled after these events were stiff. The fighting became tough. Howe was able to break through the forces of the Americans in the right wing which was situated on several hills. Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen took the opportunity to attack Chadds Ford, maiming the left wing forces of the Americans. Washington had no choice but to retreat, bringing some of Nathaniel Greene’s division. This division delayed Howe’s forces long enough to buy time for Washington’s army to escape northeast. Consequently, this left Philadelphia vulnerable, allowing the British to capture it on September 26. This occupation lasted until June 1778.

The Main Battle

The eleventh of September was greeted with a heavy fog, a blessing for the British troops for it provided them cover. General Washington received reports of different contents about the movements of the British troops. But he expected and continued to believe that Howe’s main force was going to seize the Chadds Ford. Early in the morning, Howe’s troops began marching along the Great Road from Kennet Square as they advanced on the opposing troops in Brandywine Creek.

The eleventh of September was greeted with a heavy fog, a blessing for the British troops for it provided them cover. General Washington received reports of different contents about the movements of the British troops. But he expected and continued to believe that Howe’s main force was going to seize the Chadds Ford. Early in the morning, Howe’s troops began marching along the Great Road from Kennet Square as they advanced on the opposing troops in Brandywine Creek.

A Round Of Shots Becoming a Battle

Scouts were sent by General Maxwell to gather intelligence, but they ended up in the bar, bellied up in Welch’s Tavern. Headed straight for the tavern, the British and the Americans took their first shot. The British where repulsed and they called for reinforcements as they ran to take cover in Old Kennet Meetinghouse grounds. The initial fires started in mid-morning, marking the start of the Battle Of Brandywine.

The Unexpected Flow Of The Battle

The battle grew and expanded as far as three miles away from the initial confrontation and eventually the British was able to push the lines. At 2 p.m., Howe’s decisive plan bears fruits as the British appeared on the right flank of the Americans, outflanking their brigades. The Americans never saw this strategy coming, hence they were caught in Howe’s trap.

The American Counterattack

The Americans tried to remedy the problem by repositioning their troops in order to clash with the unexpected British forces on their right flank. Sullivan, Stephen, Stirling and Hazen were the ones who reorganized their brigades for the counterattack. Howe, however, was not able to take advantage of this surprise because of his slow attack. Due to this the Americans were able to position themselves on high grounds at Birmingham Meetinghouse. However, the British forces were still strong enough to make the American division lose their ground by 4 p.m.

From Counterattack to Retreat

By 4 p.m., the fate of the battle was apparent. The Americans had to retreat and whatever reinforcements came could only delay the pursuing British forces at best. Sullivan attacked the troops that outflanked Stirling’s men. This delayed the pressing British attack, buying some time for Stirling’s men to retreat. But this heroic act only forced Sullivan to retreat because the British forces backfired and focused on his forces instead. Washington and Greene arrived and combined with other remaining troops of Sullivan, Stirling and Stephen, they tried to fight the losing battle but were only able to stop the pursuing British army for nearly an hour. They had to retreat, leaving behind many cannons since a lot of their horses that carried the artillery were killed.

Worsening Circumstances for American Troops

To add injury to the already losing battle that the Americans fought, their weakened center was further attacked by Knyphausen across Chadds Ford. Commanders Wayne and Maxwell were forced to retreat also. When evening came, the pursuit of the British army was halted because of the darkness, giving more time for the American army to retreat. The defeated Americans retreated to Chester between midnight and morning.

Battle Casualties

British official reports indicate that there were a total of 587 casualties, where 93 where killed, and 488 were wounded. Of these 587 casualties, only 40 were Hessians. Also, of the 93 killed, eight were officers, seven of them were sergeants and 78 belonging to rank and files. Of the 488 wounded, 49 were officers, 40 were sergeants, and 395 were rank and file.

There were no official reports were ever released about the casualty for the American army. Most accounts of British reports say that over 200 were killed, 750 were wounded and 400 prisoners were taken.

The Aftermath of the Battle

Howe was victorious in this battle but his lack of speed and cavalry prevented the total annihilation of the American forces. Due to poor scouting also and a poor decisions, Washington erred in leaving his right flank open. Had it been not for Sullivan and the others, their forces would have been totally wiped out.

British and Patriot forces would continue to encounter each other for the next several days, albeit these skirmishes were of lower scale. The Americans would eventually give up Philadelphia, allowing an easy capture for the British forces on September 26, 1777.