By the summer of 1777, it became clear that the Northern British forces led by General John Burgoyne were facing trouble.

By the summer of 1777, it became clear that the Northern British forces led by General John Burgoyne were facing trouble.

General Burgoyne’s plan had initially been to capture Albany in New York, which would have gained him control of the Hudson River Valley, thus dividing the American colonies in half.

By July of 1777, Burgoyne’s invasion of New York had progressed as far south as Fort Edward. He met little resistance as he led his army down the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor toward Albany. His overly ambitious plan to isolate the New England colonies would have crushed the American rebellion, and dealt the British a decisive victory against the American rebels.

But by the time August rolled around however, Burgoyne found himself embroiled in a logistics nightmare. His supply lines had grown much too long and he found himself desperately short on provisions including wagons, horses, and cattle.

As a result, his southward advance began to stall and he was faced with either finding provisions locally, or giving up some of the territory he had so easily gained in his victories at Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Hubbardton, and Fort Ann. In addition, the terrain was increasingly swampy and treacherous, and harassment by the American forces had succeeded in destroying a key supply road used by the British.

Burgoyne’s concerns were amplified when he learned in early August that Howe had abandoned his advance up the Hudson River valley and was instead marching to Philadelphia.

So acting upon a proposal made by Baron Riedesel, the commander of the German forces, Burgoyne sent a detachment of 800 troops composed primarily of mount-less Brunswick dragoons, from the Prinz Ludwig regiment out of Fort Miller on a mission to forage for horses and to acquire draft animals to assist in moving the army. This detachment was placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum.

So acting upon a proposal made by Baron Riedesel, the commander of the German forces, Burgoyne sent a detachment of 800 troops composed primarily of mount-less Brunswick dragoons, from the Prinz Ludwig regiment out of Fort Miller on a mission to forage for horses and to acquire draft animals to assist in moving the army. This detachment was placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum.

Along the way, Baum’s forces were joined by local groups of Loyalists, a few Canadians, and approximately 100 Indians. He was also lucky enough to acquire a company of British sharpshooters along the way.

Baum was initially ordered to march to the Connecticut River valley where it was believed that horses could be acquired.

As Baum was preparing to leave however, Burgoyne verbally changed the target to the supply depot at Bennington which was believed to be virtually unguarded. Burgoyne’s intelligence suggested that only 400 or so colonial militia, left over from Warner’s brigade, guarded the depot. So Baum set out on the 40 mile march to Bennington Vermont on August 11th.

Unknown to Baum or Burgoyne however, citizens of the New Hampshire Grants territory had asked the states of New Hampshire and Massachusetts for protection from Burgoyne’s army following the British capture of Ticonderoga. And on July 18th, John Stark was authorized to raise a militia using funds provided by John Langdon.

Stark managed to enlist about 1,500 New Hampshire militiamen and proceeded to the Fort at Number 4, where he crossed the river into the Grants and stopped at Manchester to confer with Warner.

While Stark was in Manchester, General Benjamin Lincoln, attempted to take control of Stark and his men. Lincoln’s earlier promotion over Stark had been the cause of Stark’s resignation from the Continental Army so Stark of course refused, claiming that he was responsible solely to the New Hampshire authorities. And with Warner as his guide, Stark marched to Vermont and proceeded to reinforce the supply depot at Bennington.

After driving off American scouts at Sancoicks Mills on August 14th, Baum received intelligence that the supply depot at Bennington had recently been reinforced with 1,500 New Hampshire militiamen under the command of General John Stark.

Baum realized that he was outnumbered almost two to one. So only five miles from the depot at Bennington, Baum halted his march at the Walloomsac River and sent a messenger to Fort Miller with a request for reinforcements.

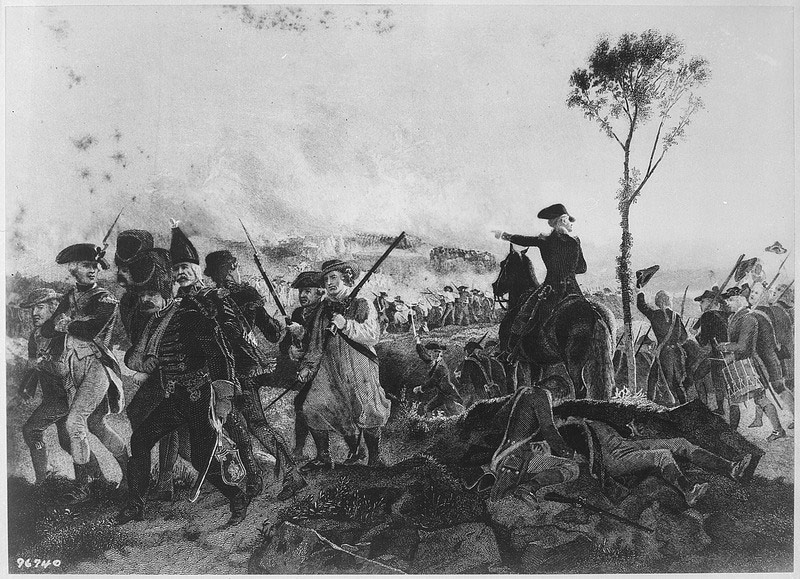

In the meantime, Stark’s scouts had informed him of the inferior size of Baum’s forces. So on the afternoon of August 16th, knowing that Baum’s forces were both outnumbered and undersupplied, Stark began positioning his forces for an attack. Stark ordered his men to surround the enemy.

Baum, hearing that the Stark’s militia had vanished into the woods, mistakenly assumed that the Americans were retreating or possibly regrouping.

To the contrary however, Stark had sent troops to flank Baum on both sides of his lines. And one of Stark’s men, hearing that the Germans spoke little or no English, had learned that the Germans were told that soldiers with little bits of white paper in their hats were allies and should not be fired upon. Stark’s men took advantage of this intelligence and placed bits of white paper in their hats. This ruse confused the Germans and gave Stark’s men a decided advantage when the fighting broke out.

Once in position, Stark’s forces proceeded to attack Baum’s defenses and were able to quickly defeat his Loyalist and Indian troops. The Hessians fought valiantly however, and were able to hold out until they began to run low on gun powder. In a final act of desperation, the Hessians launched a saber charge in a brave attempt to break free and make good their retreat. Baum was killed in the attack however and the remaining Hessians surrendered.

As Stark’s men were processing their captives, Baum’s requested reinforcements arrived from Fort Miller. Seeing that Stark’s forces were vulnerable and unprepared, Lt. Colonel Heinrich von Breymann and his forces immediately attacked Stark.

Stark quickly marshaled his troops however and was fortunately aided by the unexpected arrival of Colonel Seth Warner’s Vermont militia. Together they pushed back von Breymann’s troops and drove von Breymann from the field.

During the Battle of Bennington the British & Hessians lost nearly a quarter of their initial forces with 207 men killed and more than 700 captured while the Americans lost an estimated 40 men with 30 more wounded.

The Battle of Bennington provided a much needed morale boost for the American troops on the northern frontier. It also contributed to the British defeat at Saratoga a few months later, turning the tide of the American Revolutionary War by depriving Burgoyne’s advancing army of vital supplies.