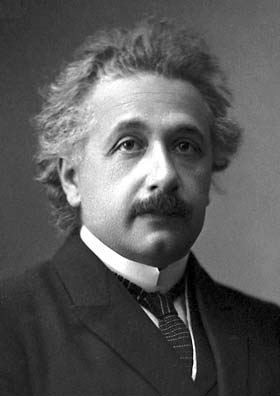

Albert Einstein was a theoretical physicist, particularly celebrated for his development of the general theory of relativity. He was born in Germany, but moved to the United States after the Nazis came to power in his homeland. Later he helped with the American war effort in World War II. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921, and his work later contributed greatly to the development of the theory of quantum mechanics. Einstein died in New Jersey in 1955, and is remembered as one of the greatest scientists of all time.

Childhood and upbringing

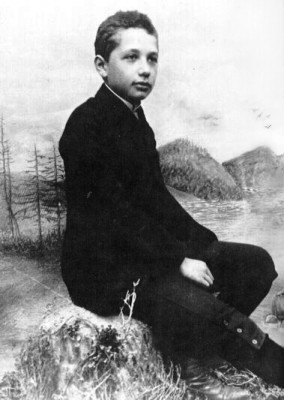

Einstein was born in the small town of Ulm, Germany on March 14, 1879, to a family of non-observant German Jews. Hermann Einstein, his father, was an engineer and salesman with a Munich company specializing in the manufacture of electrical products. The young Albert went to school in Munich, proving to be an excellent student. He also did well in his studies of music, becoming a very good violin player.

Despite these achievements, his school days were not particularly happy. Einstein struggled with a slight speech impediment and found the inflexible Prussian system of education frustrating. Even so, he would later recall that his school days had seen two events that had shaped his life. First, the discovery of a magnetic compass at the age of five, and second, a geometry book which fascinated him endlessly.

In 1889, a medical student from Poland, Max Talmud, began to join the Einstein Family for meals on Thursday evenings. Talmud took the young Einstein under his wing, teaching him about philosophy and higher mathematical concepts. One of his science books contained a passage where the author gave an image of riding alongside an electric current. This suggested to Einstein the idea that light, too, might exist in the form of a wave.

He realized that, if this were so, the beam of light would seem frozen, despite the fact that it was not still. Einstein responded to this seeming paradox by writing a piece about the effects of magnetic fields on the State of Aether, which is sometimes considered his first scientific paper. In the future, he would spend considerably more time on the problem of how substances’ appearances changed relative to the distance from their observers.

Italy and Switzerland

Hermann Einstein’s firm was unsuccessful in its attempt to win the contract to supply electricity to Munich, and so in 1894, the family moved to Milan. Albert himself remained in Munich so that he could complete his schooling. He was unhappy and lonely there, as well as dreading his imminent compulsory military service. He took advantage of a doctor’s note and went to Milan himself. His mother and father were sympathetic, but worried that a dropout who had evaded military duties would be unemployable.

Einstein decided to make a direct application to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich. He did poorly in most of the entrance tests, but excelled in the parts dealing with physics and mathematics. The school granted him admission, provided that he finish his high school studies. At the age of 17, in 1896, he graduated from high school in Aarau; while there, he met and fell in love with Marie, the daughter of the Winteler family, who ran the boarding house where he stayed.

Next, Einstein made the momentous decision to renounce his citizenship, in order to get out of doing military service in Germany. Once enrolled in the Zurich school, he found himself enjoying his education more than he had ever before. Many of his comrades from this time, such as Michele Besso and Marcel Grossman, would remain his friends throughout his life. Having now ended his romance with Marie, he also met Mileva Maric, a Serbian student of physics who he would later marry.

Trials and tribulations

Einstein graduated from the Polytechnic Institute, but was immediately faced with a number of problems. One of his professors, irritated by Einstein’s tendency to study alone rather than attending classes, wrote a scathing reference that resulted in him failing to obtain any of the academic posts he attempted to get. He took refuge in his love for Mileva, but his parents objected to both her Orthodox Christian faith and her Serbian background.

He refused to give up his lover and the couple had a daughter in 1902. Einstein was miserable as he was unable to marry the woman he loved and he was unemployed and potentially unemployable. He could not even rely on help from his father, as Hermann’s firm had collapsed. He tried his hand at being a children’s tutor, but he could not keep even those positions for long.

A few months later, however, Einstein’s fortunes began to turn. Marcel Grossman’s father agreed to give him a reference for a post in the Swiss patent office in Bern. Hermann’s health failed at around the same time, but in his last days he finally agreed that his son, now with a steady job, should be allowed to marry Mileva. The wedding was held on January 6, 1903, and in May of the following year they had the first of two sons.

The Year of Miracles

Einstein’s job required him to consider applications for patents dealing with electromagnetism. Having settled down into a routine, he used his spare time to think about the synchronization of electrical and mechanical impulses. He used the theories of James Maxwell, which he had studied during his time in Zurich, to assist in his first great discovery. He found that the speed of light was a constant. This seemed to go against Newtonian laws of motion, and led Einstein to outline the principle of relativity.

1905 was an extraordinary year for Einstein. He had four papers published in a prestigious journal, including one on special relativity, and their results would change physics for good. In one of the other papers, dealing with the equivalence of energy and matter, he included the equation e=mc^2, which became perhaps the most famous scientific equation ever devised. The discovery that small amounts of matter could become vast quantities of energy was to have immense implications for the future nuclear power industry.

The physics establishment ignored Einstein’s findings until they were picked up by Max Planck. His favorable comments led to Einstein being invited to prestigious lecturing assignments, and he was quickly offered a number of high-profile positions in academia. He progressed from the University of Zurich, to Prague, and eventually to Berlin. For twenty years after 1913 Einstein was the director of the university’s Institute for Physics. However, this success came at a price: his personal life collapsed and he divorced his wife in 1919.

Relativity

Einstein considered that the general theory of relativity, which he finished in 1915, was his most important work. He believed that the beauty of its mathematics and its superiority to Newton’s work in predicting the orbit of Mercury confirmed its correctness. According to the theory, when a planet orbited close to the sun, there should also be a deflection of light around the star. This was indeed observed during an eclipse of the sun in 1921. In the same year, Einstein received the Nobel Prize, but relativity was not yet fully accepted so the citation referenced his work on photo electricity.

Throughout the 1920s, Einstein was instrumental in helping to give birth to the new discipline of cosmology. He realized that, contrary to his earlier views, the universe was not steady, but was instead dynamically contracting or expanding. Edwin Hubble proved in 1929 that it was expanding, and the following year the two men met at California’s Mount Wilson Observatory. Einstein told Hubble that he had made a serious error in his younger days by holding to the idea of a static universe.

Although his fame was now immense in the world scientific community, the Jewish Einstein had become a major target for the Nazis, who were gaining increasing power in Germany. By the early 1930s, the government of Adolf Hitler had taken complete control of Germany, and had banned Jews from working in any official capacity. Einstein also discovered that he was kept on a list of people to be assassinated. The sense of threat was further increased when a Nazi magazine listed him as “not yet hanged.”

Einstein in America

By the end of 1932, Einstein had decided that his future did not lie in Germany. Having emigrated to the United States, he went to Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, which quickly became a center for the world’s physicists. Here, he was determined to find a “unified field theory” which would bring together the universe’s many laws and forces into one overarching whole. He was joined by a number of scientists from Europe, many of whom had fled the Nazis. They brought with them warnings of German intentions to build an atomic bomb, although Washington did not take them seriously at first.

In 1939, Einstein and one of his colleagues, Leo Szilard, were convinced by others to write to President Roosevelt and warn him of the dangers of the Nazis gaining an atomic weapon. Roosevelt, having understood that the risk of allowing Germany to develop the bomb first, invited Einstein for a meeting to discuss the subject. He was convinced of the extreme dangers of Nazi aggression in this area, and quickly set up the Manhattan Project, which aimed to produce an American atomic bomb.

Road to the Atomic Bomb

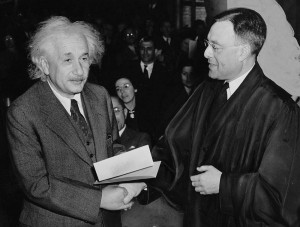

Having been accepted as a permanent resident in 1935, five years later Einstein became a citizen of the United States. Nevertheless, he was not among the group of scientists who were invited to help with the development of an American bomb. Records released in later years suggest that this snub may have been instituted by J. Edgar Hoover, the notoriously reactionary head of the FBI, who strongly objected to Einstein’s association with the causes of peace and socialism. Einstein was instead occupied in evaluating weapon designs for the Navy. He also auctioned some of his manuscripts for millions of dollars in order to raise funds for the war effort.

Einstein was on vacation in early August 1945 when he received the news that an American atomic bomb had been used to attack Hiroshima. He was horrified by the devastation that resulted, and the following year he and Szilard set up the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists. In 1947, he suggested that the United States, instead of keeping atomic technology to itself, should supply such weapons to the United Nations on the understanding that they be used only for deterrence. Einstein also became a vocal supporter of civil rights, joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Later Years and Death

Once World War II was over, Einstein returned to working on the subject of relativity, including the potential for travel in time and the possibility of black holes. However, the discoveries stemming from the atomic bomb program, which had led to the growing importance of quantum theory, meant that it was that, rather than relativity, which now occupied the minds of most of the world’s great physicists. This left Einstein somewhat isolated from his peers.

His obsessive hunt for a unified field theory also alienated Einstein from his fellow scientists, although he had a number of debates with the highly regarded atomic physicist, Niels Bohr. Einstein had now accepted that quantum theory was a legitimate part of the equation. He attempted to bring it into his theory along with gravity and light. However, he played increasingly little part in public life, traveling little and spending most of his time in wide-ranging conversations with trusted friends and colleagues.

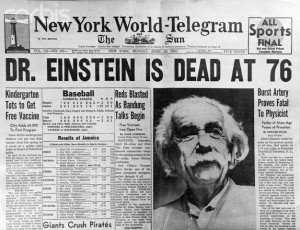

In April 1955, Einstein was preparing a speech to celebrate the seventh anniversary of the founding of the state of Israel. On the 17th, he experienced an abdominal aortic aneurysm, which caused him to bleed internally. Although he was taken to Princeton University’s medical center, he declined treatment on the grounds that he had lived a full life. He died at the center the following morning, at the age of 76. His brain was retained by the center, while his body was cremated and his ashes were scattered privately.