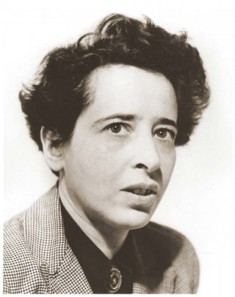

Hanna Arendt was a popular German-American political theorist. Although she is often described by many people as a philosopher, Hannah always rejected this label on grounds that philosophy is basically concerned with Man in the Singular. Instead, she described herself as an apolitical theorist since her work centers on a fact that men, not man, live on this earth and also inhabit the world. Most of her works dealt with the real nature of power, subjects of politics, authority, direct democracy and totalitarianism. The popular Hanna Arendt Prize is named in her honor.

Early Life

Hannah was born on October 14, 1906. She was born into secular family of German Jews. Her parents were Martha and Paul Arendt. Hanna grew up in Konigsberg and Berlin. She later enrolled at the University of Marburg and studied philosophy together with Martin Heidegger. According to one of her classmates, Hanna started a long and stormy romantic relationship with Martin.

Arendt was later criticized for having a relationship with Heidegger because he was known to be a supporter of the Nazi Party when he was a rector at the University of Freiburg. After breaking off the relationship with Heidegger, Hannah moved to Heidelberg where she wrote her dissertation. The book was on the concept of love in the idea of Saint Augustine.

Hannah completed her Ph.D. at the University of Heidelberg. This was after writing her first doctoral thesis on Saint Augustine with the help of Karl Jaspers. In 1929, she got married to Gunther Stern, but they divorced in 1937. With the rising popularity of the Nazi Party in Germany, Hannah found herself in deep trouble after gathering some evidence on this regime’s anti-Semitism.

Career Highlights

In 1933, Hannah fled to Paris from Germany. In Paris, she became good friends with Walter Benjamin, a critic and a philosopher. She also worked to support and help the Jewish refugees. In 1937, she was stripped of her own German citizenship. A few years later in 1940, she married a German poet and philosopher named Heinrich Blucher. Blucher was also a former member of the Communist Party.

Later that year, German troops in northern France started deporting Jews to some Nazi concentration camps in the southern part of the country. Arendt was among the people deported, but she was lucky enough to escape. After a few weeks, she left France with her husband and mother in 1941 and they all went to United States. Hiram Bingham, who was an American diplomat, was able to help them by issuing visas illegally. Hiram was able to help about 2,500 Jewish refugees escape the Nazi camps. When they arrived in New York, Arendt became a very active member of the German-Jewish community.

Later that year, German troops in northern France started deporting Jews to some Nazi concentration camps in the southern part of the country. Arendt was among the people deported, but she was lucky enough to escape. After a few weeks, she left France with her husband and mother in 1941 and they all went to United States. Hiram Bingham, who was an American diplomat, was able to help them by issuing visas illegally. Hiram was able to help about 2,500 Jewish refugees escape the Nazi camps. When they arrived in New York, Arendt became a very active member of the German-Jewish community.

Between the years 1941 and 1945, she wrote a column in a Jewish newspaper entitled Aufbau. In 1944, she directed the research for the Commission of European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction. She frequently travelled to Germany in this job.

Post WWII Highlights

Immediately after the Second World War, Arendt went to Germany where she worked for a Zionist organization – Youth Aliyah – which saved thousands of children from the Holocaust. The children were settled in Palestine. Arendt also developed a close friendship with Karl Jaspers and his wife. After a while, she started corresponding with Mary McCarthy, an American author.

In 1950, Hannah Arendt became a naturalized citizen of United States. In 1959, she was named the first female lecturer at Princeton. Between 1963 and 1967, she taught at the University of Chicago. She was also a fellow at Yale University.

Arendt’s Publications and Works

Hannah Arendt’s experiences of war may have influenced her first serious work entitled Origins of Totalitarianism, which was published in 1951. In this popular book, she talks about regimes of leaders such as Adolf Hitler.

In 1958, she published The Human Condition. In this work, she drew from the Greek culture to explain the modern world. She closely examined all the human endeavors of work, labor and action. Basically, she focused on how the endeavors played out in the four aspects of life; social, political, public and private.

In 1961, Hannah discovered that Adolf Eichmann, a famous Nazi War criminal, was held in Jerusalem. Her writings on his trial were published in 1963.

Death

Hanna Arendt died on December 4, 1975, in New York. She was 69 years old and the cause of death was a heart attack. She is buried in New York.