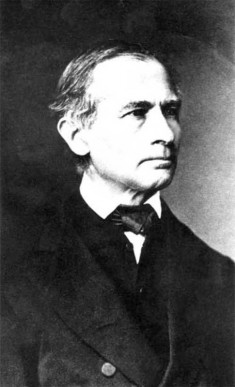

| Johann Gottfried Galle | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Astronomer | |

| Born | Jun. 9, 1812 Radis, Germany |

| Died | Jul. 10, 1910 (at age 98) Potsdam, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

Johann Gottfried Galle was a German astronomer. He was the first person to knowingly see the planet Neptune in September of 1846. Galle worked at the Berlin Observatory, using calculations previously prepared by Urbain Le Verrier to assist him in his search for the new planet. He is one of the few astronomers to have observed two returns of Halley’s Comet while active in the field. Several objects in the solar system, including one of Neptune’s rings, are named in Galle’s honor.

Early Life

Galle was born on June 9, 1812, in a remote house near the Elbe River, and was the son of a tar distillery manager. He was sent to school in nearby Radis and taught by a clergyman before moving on to secondary education in Wittenberg. In 1830, he graduated from school and went to Berlin, where he studied under a number of renowned scientists, including Johann Franz Encke.

In 1833, Galle was approved as a teacher himself, and he taught physics and mathematics at local secondary schools. In 1835, Encke had Galle hired as his assistant at the newly improved Berlin Observatory.

Growing an Interest in Astronomy

Galle remained in Berlin for 16 years and became increasingly interested in studying comets, watching with great interest as Halley’s Comet returned in 1835. He discovered several new comets himself in 1839 and 1840, which brought him recognition from the royal court. Meanwhile, he had been asked by Alexander von Humboldt to collaborate on astronomical computations, and the two men continued to associate professionally for a decade and a half. Galle, wanting to improve his knowledge of the relevant theories, attended a number of Encke’s lectures during this period.

Discovering Neptune

In 1839, Galle began a 30-year stint as the calculator of the ephemerids of the minor planet Pallas for an astronomy yearbook. He also continued to make observations and saw Saturn’s crepe ring, although he did not publish a paper about this. Thanks to financial help from government, he was able to obtain a doctorate in 1845.

In 1839, Galle began a 30-year stint as the calculator of the ephemerids of the minor planet Pallas for an astronomy yearbook. He also continued to make observations and saw Saturn’s crepe ring, although he did not publish a paper about this. Thanks to financial help from government, he was able to obtain a doctorate in 1845.

His thesis, which was based on data that had lain unanalyzed since 1706, was sent to Le Verrier, but the latter delayed acknowledgement of its receipt. However, when the message came, it told Galle that Le Verrier’s computations suggested a new planet orbiting beyond Uranus.

Because the telescopes Le Verrier had access to in Paris were thought not to be of sufficiently high quality, he encouraged Galle to take the lead in the search for the new planet. Soon after, he was searching the region that Le Varrier had mentioned, though with no success. However, Encke had a pre-publication copy of a chart containing some new data, and this allowed Galle to find an eighth-magnitude object that was not marked on this chart. Encke joined in the observations. Thanks to clement weather and good observing conditions, the planet that would be named Neptune was definitely viewed for the first time.

Galle’s Later Career

After the discovery of Neptune, Galle continued to contribute calculations and observational data in order to assist with keeping track of the new planet. As he was a rather modest man, he declined to make capital out of his discovery, and so it was Encke who gave the report to the Berlin Academy.

It was also Encke who wrote the articles giving details of how the find was made. Even so, Galle very properly received the credit for his achievement. He carried on with his work with Encke in Berlin and provided a large number of measurements of the distance of binary stars. In 1847, he produced a supplement to Olber’s list of the orbital details of comets.

Legacy and Death

In 1851, after the death of Breslau Observatory’s director, Galle was offered the position, as well as a professorial role. He was unsure about the move, as Breslau’s equipment was not as advanced as that in Berlin, but in the end the lure of undertaking independent research proved too much. He was to remain there for almost half a century.

His work during this period was not ground-breaking, but he was a popular lecturer on the subject of comets and meteors, pointing out the links between the two. He retired from his job in 1897, but lived just long enough to see the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1910, dying on July 10 at the age of 98.